The Time of Jesus’ Death and Inerrancy: Is Harmonization Plausible?

Related MediaIntroduction

The differences in the gospel record on the time of Jesus’ crucifixion have long been an enigma to Bible scholars. Mark 15:25 reads that Jesus was crucified at the third hour. Under a Jewish or common reckoning time system, which started the day at sunrise, Jesus was crucified at about nine in the morning. However, in the Gospel of John, John writes that Jesus was at his final trial before Pilate at “about (ὡς)” the sixth hour (John 19:14). If John was using the same time reckoning system as Mark, Jesus was not yet on the cross around noontime that day. On the face of it then the gospels appear to present a chronological contradiction of when Jesus was lifted up on the cross. Perhaps an alternate title to this paper would be: The Time of Jesus’ Death and Inerrancy: Was Someone’s Watch Broken? This issue has been one that has been used to argue that the Bible has real contradictions that are beyond reconciliation. In his book Jesus, Interrupted, Bart Ehrman referring to the day and time of Jesus’ death states: “It is impossible [italics supplied] that both Mark’s and John’s accounts are historically accurate, since they contradict each other on the question on when Jesus died.”2

Attempts at harmonization of the gospel accounts have included the following views: 1) a confusion of the numerals 3 and 6 in the manuscript transmission of John, 2) John’s use of a Roman time reckoning system of a civil day that started the day at midnight, 3) Mark’s reference to crucifixion as a general statement that included some event(s) that led up to the actual lifting of Jesus on the cross and, 4) the times being loose approximations that can be reconciled due to the fact that modern systems of time accuracy did not exist at the time in which the events occurred.

While a harmonization of these two accounts defies a definitive solution at least a few solutions are feasible such that the time of Jesus’ crucifixion is not a decisive proof text against inerrancy. While one cannot prove what an actual harmonized solution might be, neither can one prove an actual nonharmonistic view either. Indeed what Ehrman calls “impossible” is in fact possible within any standard evangelical definition of inerrancy including the Chicago Statement on Biblical Inerrancy.3 And more than possible, this paper suggests that plausible harmonizations can be made consistent with about any inerrancy definition.

Methods of Ancient Time Reckoning and Framework of the Crucifixion Day

In the modern age people reckon time in hours, minutes, and seconds with clocks, watches, or phones. But time reckoning in the ancient world was reckoned with hours of sunlight based on sundials. If a sundial was not available rough times were based on eyeing the sun or one’s own shadow or even just the shadow from a stick in the ground.4 Sundials were introduced into Greece as early as the 6th century BC from the Babylonians according to Herodotus (Hdt 2.109). But it was not until the 3rd century BC that they were commonly used. For night-time hour calculations there were “water clocks.” Water clocks used a steady flow drip into a container and they were in use by Roman soldiers to mark watches on the night as early as the 5th century BC. 5 Hours of daylight were divided into twelve equal parts starting at sunrise. The result was that the first hour of the day (i.e., sunrise) would be different in absolute time depending on the location on the globe and time of year. Also, an “hour” was one twelfth of the total amount of daylight time. Since the length of daylight would change depending on location and time of year, an “hour” as one twelfth of the daylight could be anywhere in from the 40’s to the 80’s in terms of minutes.6

Assuming the day of the crucifixion Friday April 3, AD 337 the sunrise in Jerusalem would have been at 5:25 a.m. according to NOAA’s (National Oceanic Association and Administration) Solar Calculator.8 Solar noon would have been at 11:41 a.m. and sunset would have been at 5:59 p.m. One “hour” on the sundial would have been equal to 62 minutes on that day. The first break of light (astronomical dawn9) would have added as much as an hour to an hour and a half of some light before a 5.25 am sunrise. So, the first “hour” of that day on a sundial would have been 5:25-6:27 a.m.

Time references from the Gospels on the day of Jesus’ crucifixion are as follows.

|

Event |

Time Indicator |

Passages that Support |

|

Peter’s denials |

Before the Rooster Crows |

Matt 26:74-75; Mark 14:72; Luke 22:60-61; John 18:27 |

|

Jesus delivered to Pilate the first time |

Early in the morning ( πρωῒ)10 |

Matt 27:1; Mark 15:1; John 18:28-29 |

|

Jesus with Pilate just before the final decision (2nd time) |

About the sixth hour |

John 19:14 |

|

Jesus Crucified |

The third hour |

Mark 15:25 |

|

Darkness falling over the earth |

The (about (ὡσεὶ) = Luke) sixth hour to the ninth |

Matt 27:45; Mark 15:33; Luke 23:44 |

|

Jesus Dies |

The (about (περὶ) = Matt) ninth hour |

Matt 27:46-50; Mark 15:34-37 |

With the exception of the issue at hand (John 19:14 and Mark 15:25), what one notices is the consistency among the gospel writers as to the other chronology of events when a time indicator is given. There is agreement that Peter denied Jesus before the rooster crowed in Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John. There is agreement between Matthew, Mark and John that Jesus was initially delivered to Pilate very early in the morning.11 There is agreement between Matthew, Mark and Luke that darkness fell over the earth at or about the sixth hour until the ninth. And there is agreement between Matthew and Mark (Luke implicitly) that Jesus died at or about the ninth hour. These points help set the chronological background needed to start examining the various views of reconciliation between Mark and John.

Proposed Views of Harmonization

The proposed views of harmonization will be taken in the general order in which they developed over time.

View One: John 19:14 Had an Original Reading of the Third Hour which was Confused for the Sixth.

In the modern era, Sabastian Bartina and C.K. Barrett raise the possibility that John 19:14 had an original reading of the third hour and an early transcriptional error between the letters of gamma (Γ= 3) and digamma (F = 6) account for the time discrepancy in the accounts.12 There is a small amount of fairly late Greek external evidence in the manuscript tradition in which John reads τριτη (3rd). The evidence for τριτη as listed in Nestle Aland 28th edition is א

(2nd corrector; 7th), Ds, L (8th), Δ (9th), Ψ (9th-10th) and l 844 with everything else on the other side. For εκτη (6th) Metzger gives some of the support in his textual commentary: P66, א*, B, E, H, I, K, M, S, U, W, Y, Γ, Θ, Λ, Π, f1, f13 and most minuscules. Most if not all the early versions support εκτη (6th) which are are: Old Latin, vg, syrp, syrh, syrpal, copsa, copbo, arm, eth, geo, pers, and al. Metzger, while noting the possibility of an early transcriptional error based on support from the church fathers, argues in favor the reading of εκτη based on the “overwhelming” manuscript evidence and sees the reading of τριτη as an “obvious attempt to harmonize the chronology with that of Mark 15:25.”13 In support of the argument of harmonization as the reason for the variation, Metzger also notes that a very few manuscripts in Mark 15:25 read εκτη (Θ, 478, syrhmg, eth), which shows some tendency of Markan scribes to harmonize with John.14

While a view of reconciling Mark and John based on early transcriptional error does not have much Greek evidence for it or any evidence from the early versions, it is the testimony of the church fathers that stands out as something that at least needs further consideration and also a closer look at how an early transcriptional error could have occurred. In fact the earliest testimony in the church record for a reconciliation between Mark and John comes on the basis of a textual error in the manuscripts of John. Metzger and Bartina suggest that the view of a textual variant being a harmonization solution to the problem goes back to at least a second/third century church father named Ammonius15 from whom Eusebius and Jerome seem to have derived their views as well.16

It should be noted that the sometimes church fathers can be difficult to assess in that at places later editors many have modified the writings. This may be the case in the longer version of Ignatius, cited below.17

Ignatius. One section of Ignatius reads: “On the day of the preparation, then, at the third hour, He received the sentence from Pilate, the Father permitting that to happen; at the sixth hour He was crucified; at the ninth hour He gave up the ghost; and before sunset He was buried” (Ignatius, The Epistle of Ignatius to the Trallians, 9 (longer version)).18

Ammonius. Ammonius writes, “‘Now it was the Preparation Day of the Passover, about the sixth hour: and he said to the Jews: Behold your king’. The Evangelist referred to the hour because the resurrection happened on the third day. The penman/copyist (καλλιγραφικός)19 instead of the Gamma element that marks the third, wrote episemon, which the Alexandrians call gabex, which signifies sixth, having much similarity [in form?]. And because of the writing error there came the discrepancy. For instead of third hour he wrote sixth”20 (Ammonii Alexandrini, Fragmenta in S. Joannem 19:14).21

Eusebius. Eusebius states, “Mark says Christ was crucified at the third hour. John says that it was at the sixth hour that Pilate took his seat on the tribunal and tried Jesus. This discrepancy is a clerical error or an earlier copyist. Gamma (Γ) signifying the third hour is very close to the episemon (ς) denoting the sixth. As Matthew, Mark and Luke agree that the darkness occurred from the sixth hour to the ninth, it is clear that Jesus, Lord and God, was crucified before the sixth hour., i.e., about the third hour, as Mark has recorded. John similarly signified that it was the third hour, but the copiest turned the gamma (Γ) into the episemon (ς) (Eusebius, Minor Supplements to Questions to Marinus, 4).22

Peter of Alexandria. Peter of Alexandria 23 indicates that the correct reading of “third” in John can be verified with the original extant manuscript, “‘For Christ our Passover was sacrificed for us,’ as has been before said, and as that chosen vessel, the apostle Paul, teaches. Now it was the preparation, about the third hour, as the accurate books have it, and the autograph copy itself of the Evangelist John, which up to this day has by divine grace been preserved in the most holy church of Ephesus, and is there adored by the faithful” (Peter of Alexander, Fragments from the Writings of Peter 5.7).24

Later fathers that follow the view of Ammonius include Jerome,25 Severus of Antioch (465-538 AD), and Theophlact (Byzantine exegete c. 1050/60).26

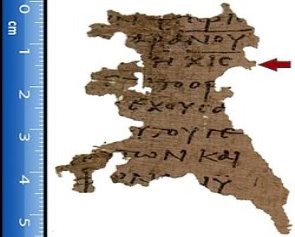

In order to understand the nature of a potential early transcriptional error one must consider the nature and shape of the digamma (also referred to as episimon or gabex) as compared to that of a gamma. During the Koine Greek era (and even before that in Attic Greek27) the digamma fell out of regular use in the Greek alphabet with the exception that it was retained for the number 6. It took the form of several shapes and therefore it could be subject to greater confusion than the more well-known Greek letters. Common early shapes prior to the Byzantine era in the classical period were an F shape as well as a square C (![]() ). It is not hard to see how either of these shapes could be confused with a gamma (Γ) as its only one small stoke of a portion of a letter. The third century papyrus P115 contains an early digamma as a rounded C seen in the image below28. It is the final letter of the number of the beast here written as 616 (Rev 13:18).

). It is not hard to see how either of these shapes could be confused with a gamma (Γ) as its only one small stoke of a portion of a letter. The third century papyrus P115 contains an early digamma as a rounded C seen in the image below28. It is the final letter of the number of the beast here written as 616 (Rev 13:18).

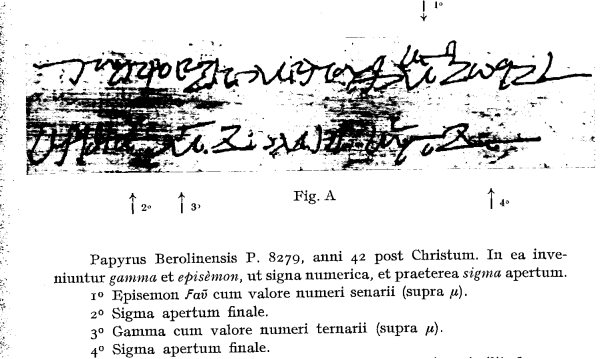

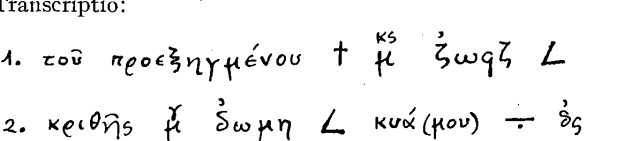

Bartina cites an even earlier papyri (nonbiblical) dated to AD 42 (Papyrus Berolinensis 8279) shown below that contains both the gamma and digamma used as numbers.29

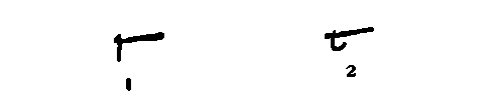

Bartina compares the letters, which he transcribed below. The first is the gamma, the second is the digamma, the only difference being the little hook at the bottom of the digamma. What is perhaps also significant about this example is the numbers in the papyri are written superscripted over other letters they are going with. This would raise the possibility that the lower part of the number could accidently connect with the upper part of another letter. One could see how this might make gamma and digamma hard to distinguish as well, since the difference between the two is a small stroke on the bottom of the digamma.

Bartina concludes that in all probability the original reading of John was “third”. He writes, “Propter omnes quae praecedunt rationed, ex contextu Evangeliorum ex critica textuali atque ex sufficientibus antiuitatis testimoniis petitas, clarum apparet, multo probabilius Io 19, 14 originaliter habuisse horam tertiam, non sextam.”30 Based on this evidence from the church fathers and the closeness of letters between gamma and digamma the theory of a textual variant (perhaps a hard to read original manuscript) as being the solution to a reconciliation with Mark is plausible.31 But based on the Greek manuscript and early evidence from the versions, it would have had to happen very close in time to the original writing.32

View Two: John is Using a Roman Civil Reckoning that Started the Day at Midnight John 19:14.

Going back to at least the 1700s, another view of reconciliation began to develop that John was using a different time reckoning system than the other gospel writers based on a day and hour reckoning that started at midnight.33 This view was picked up and brought into prominence by no less a New Testament scholar than B. F. Westcott and was carried forward by A.T. Robertson and Ben Witherington III, as well as the Holman Christian Standard Bible.34 The primary lines of argument for this view are: 1) there is good evidence that the Roman “civil” day was reckoned from midnight to midnight similar to our modern system; 2) internal evidence from John’s use of hours in the gospel fit better with a Roman civil reckoning of time than a sunrise reckoning; and 3) there is some nonbiblical evidence from Asia Minor that may suggest a Roman midnight time reckoning there.

The Roman Civil Day. There is ample evidence in the historical record that the Romans reckoned a civil day from midnight to midnight. This point is generally agreed upon. One testimony to this comes from Pliny the Elder: “The actual period of the day has been differently kept by different people: the Babylonians count the period between two sunrises, the Athenians that between the two sunsets; the Umbrians from midday to midday; the common people everywhere from dawn to dark; the Roman priests and the authorities who affixed the official day, and also the Egyptians and Hipparchus, from midnight to midnight.”35 Another writer, Plutarch (c. AD 46 – 120), asks the question, “why do they [the Romans] reckon the beginning of the day from midnight?”36

Another Roman writer Macrobius, citing an earlier source Marcus Varro (116 – 27 BC; his work, now lost, was entitled, Human Antiquites), writes, “People born in the twenty-four hours that run from one midnight to the next are said to be born on a single day.”37 Later, also Macrobius states, “The civil day as (the Romans called it) begins at the sixth hour of the night.”38 Lastly, Macrobius has commented on how Roman magistrates might see the day. He writes citing Varro: “But there are many proofs to show that the Roman people counted from one midnight to the next, just as Varro said: the Romans' sacred rites are partly diurnal and partly nocturnal, and those that are diurnal . . . , while the time from midnight on is devoted to the nocturnal rights on the following day. The customary ritual for taking auspices39also shows that the reckoning is the same: since magistrates must both take the auspices and perform the action to which the auspices were a prelude all on a single day, they take the auspices after midnight and perform the action after sunrise, and thereby are said to have taken the auspices and to have acted on the same day.”40

The Time of Martyrdoms in Asia Minor. Westcott and others also cite the time of the martyrdoms of Polycarp and Plotinus to support the view of a midnight reckoning of hours in the Roman Province of Asia Minor, the same province to which John was likely writing. Such martyrdoms, it is argued, normally took place in the morning.41 Polycarp is said to have been martyred at Smyrna at the eighth hour (Mart. Poly. 21) while a later Christian Pionius was killed at the tenth hour also at Smyrna.42

Other References to Time in John and the Synoptics. From the biblical text there may be some indication to support the day starting at midnight in the Roman conception. Matthew records “As he was sitting on the judgment seat, his wife sent a message to him: “Have nothing to do with that innocent man; I have suffered greatly as a result of a dream about him today [italics supplied]” (Matt 27:19). Pilate’s wife, presumably Roman, refers to a night dream she had as being that day, the day of Pilate’s meeting with Jesus. Westcott contrasts this statement with a “Jewish” conception of a day based on Jesus’ statement, “Are there not twelve hours in a day?”

(John 11:9).43 Robertson adds the following passage to show that there is indeed a contrast with the Synoptics on how John views the “day” on the night of the resurrection. In Luke on the road to Emmaus, two disciples urge Jesus, “Stay with us, because it is getting toward evening and the day is almost done” (Luke 24:29 cf. v. 36). After dinner, Jesus travels about 7 miles to Jerusalem where he meets the eleven disciples. In John the same day referenced in Luke extends into the evening. John writes, “On the evening of that day, the first day of the week, the disciples had gathered together and locked the doors of the place because they were afraid of the Jewish leaders. Jesus came and stood among them and said to them, “Peace be with you” (John 20:19). Robertson considers this argument as “conclusive” that John is using a Roman conception of the day.44

John makes reference to hours of time in three places in addition to John 19:14

(John 1:39; 4:6, 52). These some have argued better support a view of time reckoning that starts the day at midnight. 45 In John 1:39, two disciples come and meet Jesus after which they stayed with him “that day (τὴν ἡμέραν ἐκείνην).” John adds it was the 10th hour when they met him. Under a normal Jewish reckoning this would be 4 in the afternoon an unusual time to begin a day’s stay. Under a midnight reckoning the time would be 10 in the morning.

In John 4:6, Jesus meets the Samaritan woman at the well. Jesus had left Judea and wearied from his journey he came to the well. John said this was about the 6th hour. While one could imagine being weary at about noon or at six p.m.,46 the distance from Jerusalem to Sychar is well over 30 miles. Walking at a normal pace of about 3 miles per hour and assuming no overnight stops, it would have been difficult to get there by noon. Also, it is argued that a more natural time for drawing water and the assignment of the disciples to go for purchase of food would be toward evening than at noon. 47

Lastly, there is the noblemen from Capernaum who comes to Cana to meet Jesus and requests that Jesus heal his son, which Jesus does at the “seventh hour.” Jesus does not go to Capernaum but speaks a word of healing from Cana. The nobleman does not make the return journey about 20 miles until the next day. It could be reasoned that if the time was only one in the afternoon he would have returned that day to see his son, but a Roman reckoning from noon would have made it seven in the evening, too late to return that night.48

While these arguments may be initially impressive, there have been serious counterarguments that make a midnight time reckoning less than definitive and many have rejected it for ultimately a lack of convincing evidence. The main arguments against John using a reckoning of time from midnight can be summarized into four areas.

First, though it is acknowledged that a Roman civil day reckoning from midnight was the way Romans viewed whole civil days, there is no direct evidence that day-hour reckoning was done other than by daylight hours as seen in the literature and sundials. W. M. Ramsay colorfully writes, “This [Roman] supposed second method of reckoning the hours is a mere fiction, constructed as a refuge of despairing harmonisers, not a jot of evidence for it has ever been given that will bear scrutiny.”49 Ramsey also points out a reading in Codex Bezae (Acts 19:9) in which Paul taught at the school of Tyrannus at Ephesus from the fifth to the tenth hour. He feels it would have been better suited for post vocational work time which ceased one hour before noon.50 It is also worthy of note that though the early church fathers such as Eusebius were aware of the apparent conflict of times in John and Mark and living in the Roman era, none of them wrote about a “Roman” reckoning as the solution.51 In addition to the Synoptic gospel writers, Josephus and Philo appear to use a normal daylight reckoning of hours.52 Also, as the earlier quote from Pliny indicated the “common people everywhere” reckoned the day from dawn to sunset. It could be asked, wasn’t John writing to the common man?

The other piece of evidence to consider is from the sundials. Morris calls attention to Roman sundials that mark noon with the number 6 as opposed to 12.53 While Morris’ point is valid it must be qualified at least in two ways. First, based on Gibbs’ catalogue of existing sundials from the Greco Roman world from the 3rd century BC to the 4th century AD, most of these do not have the number markings rather just lines representing the twelve hours of daylight. Also, for ones that have markings, at least in one case of a Ptolemaic era sundial, Gibbs notes that the numbers probably have been added later in the Byzantine era.54

The sundial above was discovered in the 1800s at Aphrodisias, Turkey, in the ancient Roman Province of Asia Minor. It is dedicated to Roman Emperor Caracalla (Marcus Aurelius Severus Antonius (reign from 161-180 AD) and his mother Julia.55 One should notice the Greek digamma mark (= 6) in the middle of the dial.

Second, the evidence of the time of martyrdom of Polycarp is at least debatable and a case can be made that he was martyred in the afternoon after the games were over. Ramsay attempts to make the point that closer reading of when Polycarp was martyred indicates the games were over and this would have been unlikely if the eighth hour were eight in the morning. But looking at this again the text only says that after the crowd asked that Polycarp be fed to a lion that the wild animal parts of the show were over not that all games and festivities were over.56 The fact that the whole crowd and the magistrate were all in the stadium suggests that some festivities were still taking place. Another possibility, as Ramsay noted was his first interpretation of the passage, was to understand that the wild animal exhibitions had taken place on a previous day.57 So though this piece of data is still a possibility for supporting a midnight reckoning of time, its ambiguity undermines the midnight time reckoning view.

Third, though the reference to time in hours in John may favor a Roman civil reckoning of time, the data is not conclusive because it must be framed in probabilities and not absolutes. 58 And fourth, some have also pointed out that a final verdict by Pilate at about 6:00 a.m. would not have allowed enough time for all the events that precede the verdict.59 These events include Pilate sending Jesus to Herod Antipas (Luke 23:6-12) and the flogging of Jesus

(John 19:1) before he was brought out for Pilate’s final verdict. But this final argument does not hold up that well. Jesus is brought to Pilate before sunrise in the range of 3-6 if πρωῒ is considered the fourth watch of the night, or if it starts with dawn, perhaps at hour to an hour and a half between the break of dawn and sunrise. Jesus did not respond to Antipas therefore he probably did not stay with him that long. Indeed a noon reckoning for John may allow too much time (over six hours) between Jesus’ first and second appearance before Pilate.60

View Three: Mark’s Reference to Crucifixion is a General Statement that Included Some Event(s) that Led Up to the Lifting of Jesus on the Cross

Augustine may have been one of the first to articulate and record that a closer look at Mark may be the solution to this issue. He considered that Mark was indicating that the cry to crucify Jesus by the Jewish nation is what took place at the third hour and thus they were the ones truly responsible for Jesus’s death. He writes, “Then Pilate in his judgment seat judged and condemned him, about the sixth hour, they took the Lord Jesus Christ and led him out. ‘And carrying a cross for himself, he went out to that place which is called Calvary, in Hebrew Golgotha, where they crucified him.” What is it, therefore, that the Evangelist Mark says, ‘Now it was the third hour and they crucified him,” except at the third hour the Lord was crucified by the tongues of the Jews, at the sixth hour by the hands of the soldiers?”61

In a similar vein, Mahoney interprets the time reference in Mark not when Jesus was lifted on the cross but at an earlier event of the dividing of Jesus’ garments.62 To support this, he repunctuates the reference to the third hour to go with the preceding phrase as opposed to the following. His translation is the following: “And they crucify him, and divide his garments, casting lots upon them, what each should take (but [καὶ] it was the third hour). And they crucified him and the inscription . . ..”63 Miller suggests the possibility that the aorist tense for “crucify” (ἐσταύρωσαν) might be ingressive stressing the beginning of the action (they began to crucify him).64

While these views are worthy of consideration, a few significant objections can be raised. In regard to Augustine, it would require to take the term crucifixion metaphorically in

Mark 15:25, but literally in the same passage in Mark 15:24. In addition, the referent to “they” would have to shift from the Romans in verse 24 to the Jews in verse 25, without much indication that a shift has been made (Then they [Romans] crucified him and divided his clothes, throwing dice for them, to decide what each would take. 25 It was nine o’clock in the morning when [and] they [Jews] crucified him. Mark 15:24-25). Mahoney makes a good point that many translations bias the interpretation by translating the καὶ as “when.” But the case of Mahoney would be better supported if the only reference to crucifixion followed the reference to the third hour. In this case a statement of crucifixion occurs both before and after the reference to the third hour. One must also ask the question of why give a parenthetical time comment for less important event of the dividing of the garments as opposed to the lifting of Jesus on the cross. While these views are possible, it is hard to make the case they are probable and they have not gained any measure of general acceptance.

View Four: Time Approximation Allows for Adequate Harmonization of Mark and John

What appears to be the currently prevalent view in the evangelical literature of those arguing for harmonization is that time approximation can account for a reconciliation of the two passages. Modern standards can speak of time in terms of minutes and seconds. Sundials presented times in terms of hours, while eyeing the sun or shadow length perhaps one could say early morning, midmorning, midday etc. Köstenberger writes, “since people related the estimated time to the closest three-hour mark, anytime between 9:00 a.m. and noon may have led one person to say that an event occurred at the third (9:00 a.m.) or the sixth hour (12:00 noon).”65 Similarly, Morris writes, “People in antiquity did not have clocks or watches, and the reckoning of time was always very approximate. The ‘third hour’ may denote nothing more form than a time about the middle of the morning, while ‘about the sixth hour’ can well signify getting on towards noon. Late morning would suit both expressions unless there were some reason for thinking that either was being given with more than usual accuracy. No such reason exists here.”66 Stein commenting on Mark concludes, “If we recognize the general preference of the third or sixth hour to designate a period between 9:00 a.m. and noon and the lack of precision in telling time in the first century, the two different time designations do not present an insurmountable problem.”67

While everyone agrees that ancient methods of time reference do not carry modern precision and that time approximation is taking place, the question remains how much approximation is being used by the gospel writers, and are approximations loose enough to account for a reconciliation of the two passages. For example, John refers to actual events with the seventh hour and the tenth hour (John 1:39). He is not using three hour increments but perhaps rather one hour increments. Matthew refers to the eleventh hour in a parable (Matt 20:9). One hour increments would be consistent with normal ancient sundial measurements. If both Mark and John used time tolerations of plus or minus an hour, time approximation would not produce a reconciliation. In Mark, Jesus would be on the cross as late as about 10:00 a.m., while in John Jesus would be before Pilate about 11:00am. But one has to ask the question, especially about Mark, if his time is coming from a sundial or is it a more general approximation based on eyeing the sun or a shadow. If this is the case, perhaps a two hour time tolerance is reasonable which could place the crucifixion as late as about 11:00 a.m.68 Greater allowance for time approximation for Mark seems warranted when his references are compared with Matthew and Luke. For example Mark says “when the sixth hour had come (γενομένης ὥρας ἕκτης), darkness fell over the whole land” (Mark 15:33). But in Luke the darkness is said to come about the sixth hour (ὡσεὶ ὥρα ἕκτη) (Luke 23:44). Similarly, Mark says that Jesus was at his last moments of death, crying out why God had forsaken him, at the ninth hour (τῇ ἐνάτῃ ὥρᾳ; Mark 15:34). Matthew though says the last moment of Jesus took place around/about the ninth hour (περὶ δὲ τὴν ἐνάτην ὥραν (Matt 27:46). It is significant that both Matthew and Luke interpret these times as approximate while Mark does not give an explicit time approximation qualifier. For the sake of argument, if Jesus was before Pilate at 10:30 and crucified shortly thereafter, perhaps one writer could say it was midmorning and another about midday with a reasonable time approximation. The time approximation view of reconciliation is feasible but also it is strained.69 Also, it would have to be time approximation for at least one of the gospel writers without a sundial level of accuracy.

The Time of Jesus’s Death and Inerrancy

The time of Jesus’ death has truly been a puzzle for anyone who has looked at this issue. All of the views for reconciliation have good arguments against them, but good arguments are not the same as decisive arguments. At least three resolutions (confusion of letters of gamma and digamma, Roman civil reckoning of John, and time approximation) in this writer’s view are plausible. In considering how the time of Jesus’s death relates to the doctrine of inerrancy, the evangelical can look to a standard definition of inerrancy as articulated by the Chicago statement in particular articles 10, 13 and 14. These read:

Article X We affirm that inspiration, strictly speaking, applies only to the autographic text of Scripture, which in the providence of God can be ascertained from available manuscripts with great accuracy. We further affirm that copies and translations of Scripture are the Word of God to the extent that they faithfully represent the original. We deny that any essential element of the Christian faith is affected by the absence of the autographs. We further deny that this absence renders the assertion of Biblical inerrancy invalid or irrelevant.

Article XIII We affirm the propriety of using inerrancy as a theological term with reference to the complete truthfulness of Scripture. We deny that it is proper to evaluate Scripture according to standards of truth and error that are alien to its usage or purpose. We further deny that inerrancy is negated by Biblical phenomena such as a lack of modern technical precision, irregularities of grammar or spelling, observational descriptions of nature, the reporting of falsehoods, the use of hyperbole and round numbers, the topical arrangement of material, variant selections of material in parallel accounts, or the use of free citations.

Article XIV We affirm the unity and internal consistency of Scripture. We deny that alleged errors and discrepancies that have not yet been resolved vitiate the truth claims of the Bible.70

Conclusion

In summary, inerrancy applies to the original autographs of the Bible, does not require “modern technical precision,” and is not negated by differences in parallel passages that have not been resolved. So, while the time of Jesus’ death as a case study does not prove the doctrine of inerrancy neither does it disprove it either. One area that could use further research would be to look at ancient Roman court records for hour reckonings to see if they indeed reflect a Roman civil day or if they refer to daylight hours.

Regardless of one’s view to a potential solution, exegetes and Bible translators need to be cautious that they do not communicate to English readers times and other measurements that express a greater level of precision than is really there. In regard to times, this is certainly the case. For example if someone sees 9:00 a.m. in a commentary or Bible translation they probably assume it does not mean 8:50 or 9:15. Even when the first hour started and how long an hour lasted in the ancient world lasted was dependent on location and time of year; this convention has great variance with the way modern time is communicated and most Christians are completely unaware of this point. Another point of encouragement would be for Bible translations to put the textual variant of “three” in John 19:14, something to the effect that a few manuscripts have it. This seems warranted due to the possibility of a transcriptional error and testimony of the church fathers. All would agree that the gospel writers place much more emphasis of what Jesus did rather when he did it. The few time indicators that we have though fit their purpose in communicating those critical events the day Jesus died. And for their accounts of this day in history we are eternally grateful.

1 This paper was presented on November 21 at the 2013 annual meeting of the Evangelical Theological Society in Baltimore, Maryland.

2 Bart D. Ehrman, Jesus Interrupted – Revealing the Hidden Contradictions in the Bible (and Why We Don’t Know About Them) (Harper One, New York, 2009), 29.

3 Formalized in 1978 by numerous and prominent evangelical Christian leaders at a conference sponsored by the International Council on Biblical Inerrancy the Chicago Statement on Biblical Inerrancy is perhaps the most thorough explanation on the meaning of inerrancy that has been able to muster a broad consensus in the evangelical scholarly community. The original copy of the manuscript is contained in the archives at the Dallas Theological Seminary Library.

4 The reference to the use of one’s shadow or even a stick in the ground as a common technique was given to me by Frank King, President of the British Sundial Society in a personal email dated October 15, 2013.

5 Simon Hornblower and Anthony Spawforth, eds., The Oxford Classical Dictionary (3rd ed.; Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1996), 350.

6 Gibbs writes, “Greek and Roman sundials always marked the 12 seasonal hours of daylight from between sunrise and sunset. But while the seasonal hours were of equal length during a given day, their length varied during the year, being shortest at the winter solstice and longest at the summer solstice.” Sharon Gibbs, Greek and Roman Sundials (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1976), 4. Gibbs also notes that over 30 sundials have been excavated at Pompeii in various public places and homes indicating how common they were in a city of that size in the first century. Ibid., 5.

7 See Harold Hoehner, Chronological Aspects of the Life of Christ (Academie Books, Grand Rapids: 1977), 114. The two major views on the year of the crucifixion are 30 and 33 AD. But the time of the sunrise is more dependent on the day of the year and location than the year itself.

8 http://www.esrl.noaa.gov/gmd/grad/solcalc/sunrise.html (Date accessed September 28, 2013).

9 Astronomical dawn is defined at the point in time when total darkness is first broken, the sun being 24 degrees under the horizon. Nautical dawn would be the sun 18 degrees under the horizon and civil dawn would be the sun 12 degrees under the horizon. At the equator, length of times for these various stages would be the shortest on the earth at 24 minutes each. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dawn (Accessed October 18, 2013). In Jerusalem which is north of the equator these time spans of dawn would be slightly longer.

10 BDAG defines as the noun Πρωΐα “early part of the daylight period, (early) morning”, and the adverb πρωῒ as “the early part of the daylight period, early, early in the morning,” BDAG, 892. Louw and Nida define πρωῒ as “the early part of the daylight period - `early morning.’” Πρωῒ appears to be the term used before sunrise daylight hours (first hour etc) are used and can refer to the timeframe when it is still dark. See Mark 1:35 Καὶ πρωῒ ἔννυχα λίαν ἀναστὰς ἐξῆλθεν καὶ ἀπῆλθεν εἰς ἔρημον τόπον κἀκεῖ προσηύχετο.

11 The phases of Jesus’ trial can be tabulated as follows: 1) An initial inquiry before the former High Priest Annas (John 18:13) 2) An evening examination with Caiaphas presiding.

(Mark 14:55-64; Matt 26:59-66); 3) A morning confirmation before the entire Sanhedrin

( Mark 15:1a Matt 27:1; Luke 22:66-71); 4) An initial meeting with Pilate (Mark 15:1b-5; Matt 27:2, 11-14; Luke 23:1-5; John 18:29-38); 5) A meeting with Herod Antipas (Luke 23:6-12); 6) A more public trial before Pilate; Luke: 23:13-16; Matt 27:15-23; Mark 15: 6-14; Luke 23:17-23; John 18:39-40). Darrell Bock, Luke (BECNT; Grand Rapids: Baker, 1993), 2:1793.

12 Sebastian Bartina, S.J., “Ignotum Episemon Gabex,” Verbum Domini 36 (1958), 16-37. C. K. Barrett, The Gospel According to St. John – An Introduction with Commentary and Notes on the Greek Text (2nd ed; Philadelphia: The Westminster Press, 1978), 545.

13 Bruce Metzger, A Textual Commentary on the Greek New Testament (2nd ed; Stuggart: Deutsche Bibelgesellschaft, 1994), 216.

14 Metzger does not give the reading selected a rating of certainty (A, B, D, or D). Ibid., 99.

15 Perhaps Ammonius Saccus (AD 175-242) the supposed founder of Neoplatonism or perhaps another Ammonius that predated Eusebius. Eusebius credits a man from Alexandria named Ammonius with being the forerunner of his Eusebian canons which was a systematic effort of a numbering system that would show parallel passages in the gospels. See F.L. Cross and E.A. Livingston, eds., The Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1997) 52-53, 573-574. See also Nestle-Aland, Novum Testamentum Graece (28th ed.; Stuttgart: Deutsche Bibelgesellschaft: 2012), 89-90.

16 Bruce Metzger, A Textual Commentary on the Greek New Testament, 216. Sebastian Bartina, S.J., “Ignotum Episemon Gabex,” Verbum Domini 36 (1958), 30.

17 Joel C. Elowsky, ed., Ancient Commentary on Scripture John 11-21 (Vol IVb; Downers Grove, IL: Intervarsity Press, 2007), 304.

18 Roberts and James Donaldson, eds., The Ante-Nicene Fathers (10 vols; Peabody, MA: Hendrickson Publishers, 1994), 1:70. Joel C. Elowsky, ed., Ancient Commentary on Scripture John 11-21 (Vol IVb; Downers Grove, IL: Intervarsity Press, 2007), 304. Holmes dates the letters of Ignatius sometime around 110 AD. Michael Holmes, ed., The Apostolic Fathers (2nd ed; Grand Rapids, Baker Book House, 1989), 82

19 Liddell and Scott indicate that this word can refer to a penman or copiest. They note another passage where a copyist error is referred to (Steph. In Hp.2.407). LSJ, “καλλιγραφικός,” 867.

20 Authors own translation using the Greek and the Latin.

21 The Latin translation reads: “Erat autem parasceve Paschae, hora quasi sexta, et dicit Judaeis: Ecce rex vester. Horam evangelista denotavit propter resurrectionem tertio die factam. Insignis autem scriba pro Gamma elemento, quod tertiam signat, aliud signum posuit, quod Gabex Alexandrini vocant, et sextum denotat, magnamque inter se habent similitudinem: et ex errore scriptionis ista irrepsit diversitas lectionis. Nam pro tertia hora sextam scriptsit.” J. P. Migne, Patrologia Graeca, LXXV, col. 1512.

22 Quote taken from Joel C. Elowsky, ed., Ancient Commentary on Scripture John 11-21 (Vol IVb; Downers Grove, IL: Intervarsity Press, 2007), 304. See also P.G. Migne Patrologia Graeca, XXII, col. 1009.

23 Peter of Alexandria’s death is dated about 311 AD. He was bishop of Alexandria starting in about 300 AD. Cross and Livingston, eds., The Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church, 1263-64.

24 ANF, 6:282.

25 P.G. Migne, Patrologia Latina, XXVII, col. 1108c.

26 Joel C. Elowsky, ed., Ancient Commentary on Scripture John 11-21, 304. Cross and Livingston, eds., The Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church, 1491, 1607.

27 Herbert Weir Smyth, Greek Grammar (Harvard: Harvard University Press, 1920), 125.

28 Image taken from http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Digamma. (Date accessed November 1, 2013).

29 Bartina, S.J., “Ignotum Episemon Gabex,” 37.

30 A rough translation is as follows: “Due to of all that has been reasoned before, from the context of the Gospels, from textual criticism and from sufficient ancient testimony, it appears clear, it is more probable that Jn 19, 14 originally had the third hour not the sixth.” Ibid.

31 Even some like Hodges and Farstad who hold almost exclusively to the majority of manuscripts note, “Occasionally a transcriptional consideration outweighs even a preponderance of contradictory testimony. . .” Zane C. Hodges and Arthur L. Farstad, The Greek New Testament according to the Majority Text (2nd ed.; Nashville: Thomas Nelson Publishers: 1985), xxii.

32 McClellan notes that early textual critics Theodore Bezae and J.A. Bengel adopted this view. John Brown McClellan, The New Testament of our Lord and Savior Jesus Christ (London: Macmillan, 1875), 738.

33 Ibid., 740.

34 B. F. Westcott, The Gospel according to Saint John (London: John Murray, 1908. Reprint; Grand Rapids: Baker Book House, 1980), 324-26. A. T. Robertson, A Harmony of the Gospels for Students of the Life of Christ (New York: Harper and Row Publishers, 1950), 286-87. Ben Witherington, III, John’s Wisdom – A Commentary on the Fourth Gospel (Louisville, KY: Westminster John Knox Press, 1995), 294. The Holman Christian Standard Bible reads: “It was the preparation day for the Passover, and it was about six in the morning. Then he told the Jews, ‘Here is your king!’” (John 19:14 HCSB).

35 Pliny, Natural History 2.77 (188). Loeb Classical Library, 319. Pliny later states in the same section: “A. Gellius, iii. 3, informs us, that the question concerning the commencement of the day was one of the topics discussed by Varro, in his book “Rerum Humanarum:” this work is lost. We learn from the notes of Hardouin, Lemaire, i. 399, that there are certain countries in which all these various modes of computation are still practised; the last-mentioned is the one commonly employed in Europe.”

36 Plutarch, Questions, 84.

37 Macrobius, Saturnalia, 1.3.2. Loeb Classical Library, 23.

38 Ibid., 1.3.10.

39 i.e., asking advice or guidance from the gods.

40 The text goes on to say that a slave, if he has left after midnight and returned before the next midnight, is only considered to be absent one day. Ibid., 1.3.8. Witherington who sees a Roman time reckoning as “likely” makes the point that Romans “were known for dealing with such matters the first thing in the morning, and Pilate is likely to have followed the same practice.” Ben Witherington, III, John’s Wisdom – A Commentary on the Fourth Gospel, 294. In a footnote he writes, speaking of Pilate’s decision and the time of it, “What may be significant is that this particular form of Roman recognition was used in official documents and for legal purposes. We have seen the interest of the evangelist throughout in presenting the story of ‘Jesus on trial’ and there is a certain fitness to have it close with a sort of time marker used in Roman legal proceedings.” Ibid., 400.

41 Philo is sometimes cited as evidence for this view. “the spectacle of their sufferings was divided; for the first part of the exhibition lasted from the morning (πρῶτος) to the third or fourth hour, in which the Jews were scourged, were hung up, were tortured on the wheel, were condemned, and were dragged to execution through the middle of the orchestra; and after this beautiful exhibition came the dancers, and the buffoons, and the flute-players, and all the other diversions of the theatrical contests” (Philo, Flaccum, 1:85). Translation taken from Bibleworks 9.0.

42 McClellan, The New Testament of our Lord and Savior Jesus Christ, 742.

43 B. F. Westcott, The Gospel according to Saint John, 324-25.

44 A. T. Robertson, A Harmony of the Gospels for Students of the Life of Christ, 286-87.

45 See Norman Walker, “Reckoning of Hours in the Fourth Gospel,” Novum Testamentum 4 (1960), 69-73.

46 Köstenberger cites a case in Josephus (Ant. 2.11.1) were some one was wearied at about midday. Andreas Köstenberger John (The Baker Exegetical Commentary of the New Testament; Grand Rapids: Baker Book House, 2004), 147.

47 Norman L. Geisler and Thomas Howe, The Big Book of Bible Difficulties (Grand Rapids: Baker Book House, 1992), 376.

48 Walker, “The Reckoning of Hours in the Fourth Gospel,” 69-70.

49 W. M. Ramsay, “About the Sixth Hour,” The Expositor 4.7 (1893), 220.

50 Ibid., 223. Tischendorf records this variant. See Constantinus Tischendorf, Novum Testamentum Graece (8th ed.; Lipsiae: Giesecke & Devrient, 1872), 2. 166.

51 J. A. Cross, “The Hours of the Day in the Fourth Gospel,” Classical Review 5.6 (June 1891), 245. Johnny V. Miller, “The Time of the Crucifixion,” Journal of the Evangelical Theological Society 26.2 (1983), 165.

52 One clear passage from Josephus is from Life where a lunch (ἀριστοποιέω) is said the be at the sixth hour (Life, 279). One place in Philo is the reference to Jewish persecutions in the third or fourth hour which are probably to be reckoned from the first hour of the morning. See Philo, Flaccum, 1:85.

53 Leon Morris, The Gospel according to John (NICNT; Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1971), 158.

54 Gibbs, Greek and Roman Sundials, 304.

55 Ibid., 169.

56 This proclamation having been made by the herald, the whole multitude both of the heathen and Jews, who dwelt at Smyrna, cried out with uncontrollable fury, and in a loud voice, “This is the teacher of Asia, the father of the Christians, and the overthrower of our gods, he who has been teaching many not to sacrifice, or to worship the gods.” Speaking thus, they cried out, and besought Philip the Asiarch to let loose a lion upon Polycarp. But Philip answered that it was not lawful for him to do so, seeing the shows of wild beasts (τὰ κυνηγέσια) were already finished (Martyrdom of Polycarp, 12:2). Also, Philo notes that in the shows which started with the persecution of Jews the first portion of is lasted from the first (πρῶτος) to the third or fourth hour (Philo, Flaccum, 1:85). Translation taken from Bibleworks 9.0.

57 Ramsey, “About the Sixth Hour,” 221, footnote 2.

58 A. Plummer, The Gospel According to St. John (Cambridge: University Press, 1906), 342.

59 See Craig S. Keener, The Gospel of John – A Commentary (2 vols.; Grand Rapids: Baker, 2003), 2:1130.

60 Finegan in his Handbook of Biblical Chronology adopts the Roman civil reckoning view in its first edition. Jack Finegan, Handbook of Biblical Chronology (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1964), Sec. 453. But Finegan in the second edition changes to the view that Mark and John are irreconcilable with Mark being an “interpolation.” Jack Finegan, Handbook of Biblical Chronology (Revised ed; Peabody, MA: Hendrickson Publishers, 1998), Sec. 614.

61 Augustine, Tractates on the Gospel of John 117.1. Translation taken from John W. Rettig trans. The Fathers of the Church – Tractates on the Gospel of John 112-24-Tractates on the First Epistle of John (Washington D.C. The Catholic University of America Press, 1995), 33.

62 Aidan Mahoney, “A New Look at the Third Hour of Mk 15,25,” CBQ 28 (1966), 292-299.

63 Ibid., 294.

64 Miller though opts for time approximation and being the best solution to this issue. John Miller, “The Time of the Crucifixion,” JETS 26.2 (June 1983), 165. Miller also notes that there is a textual variant in which D, it, samss read εφυλασσον (they guarded) which supports the time reference being something other than the actual lifting of Jesus on the cross.

65 Andreas Köstenberger, John, 538.

66 Leon Morris, The Gospel according to John, 801.

67 Mark Stein, Mark (BECNT; Grand Rapids: Baker, 2008), 713.

68 Mark’s only time references in regard to the “hour” are on the day of the crucifixion. Mark 15:25 (Jesus crucified; third hour), Mark 15:33 (darkness fell; sixth hour) and Mark 15:34 (Jesus died; ninth hour).

69 One that for those used to looking at the sun for time indicators solar noon would be one of the easier times to identify.

70http://www.reformed.org/documents/index.html?mainframe=http://www.reformed.org/documents/icbi.html (Date accessed November 8, 2013).

Related Topics: Apologetics, Bibliology (The Written Word), Christology, Crucifixion, Cultural Issues