Part Va: CANONIZATION — Chapter Six: The Collection Begins

Related Media|

Preparing the Way

|

Some time ago “Ron,” a local high school teacher, staggered into my office in a mild state of shock. He looked as though he had just tackled a tiger and lost. That was about it too. He needed help fast. Just that day he had been sharing his faith with a colleague and had been shot down in flames. In the heat of the battle Ron’s associate had challenged his authority—the Bible. Although it was an old argument, my friend had never met it before. It obviously had knocked him off balance. His fellow teacher had simply rejected the Bible. This wasn’t what sent my friend reeling however. It was the reason.

According to his antagonist, the Bible is merely a collection of books put together by men long after the days of Christ. He noted there was little agreement among these men. Different collections exist. “How do you know your Bible contains all the books it should contain?” he asked. He pointed out that there may be other worthy books overlooked! He wondered how Ron could be sure that some unworthy books had not been unwarrantedly placed in the collection. Some may have been included by mistake!

My beleaguered and beaten friend needed some answers. Who did the collecting? Can we be sure the collection is a reliable one? Why do we have sixty-six books in our Bible instead of sixty-four? Are there some that really don’t belong there? Why do we have sixty-six instead of the seventy-seven found in some Bibles? Are there some that have been lost or that we have failed to recognize?

These questions relate to the canon of Scripture—the subject of our study in this and the following chapter.

To hold his own in the teachers’ lounge that day, Ron needed answers to these very questions. He needed some background. He had to understand the process in order to eliminate the problems. A few simple facts would quickly dislodge his colleague from his rather pompous pedestal.

I. A Word of Explanation

The term “canon” is derived from a Greek word meaning a staff, straight rod, rule or standard. This Greek word was derived in turn from the Sumerian word that originally meant a “reed” (Job 40:21). Because reeds were often used as measuring sticks, in a figurative sense the word implied straightness or uprightness and was used for a measuring standard or norm. It was not until c. A.D. 352 that the word was first used by Athanasius in reference to the divinely inspired books of Scripture. The “canon” therefore is the collection of writings that constitute the authoritative and final norm, rule, or standard for our faith and practice. In short, the canon comprises the writings of the Bible, both the Old and New Testaments. The Bible is called the canon because it is the objective rule for measuring, or judging, all matters of doctrine and life.

If the word “canon” implies the status of the Bible by virtue of its inspiration, the word “canonicity” often applies to the recognition of this status by the church. It is the process by which the various books of the Bible were brought together and their value as the Word of God recognized. One scholar speaks of canonicity as “die churches’ recognition of the authority and extent of inspired writings.”1

Perhaps the most helpful way to get a hold on this immense topic is to slice it in half. Surely the most appropriate place to apply the knife is at the very point of division in our English Bible. In this lesson, then, we will concentrate only upon the collection of the Hebrew manuscripts in our Old Testament.

II. The Test

It is obvious that the thirty-nine books of our Old Testament constitute only a small part of the literature that came from the pens of the children of Israel before Christ. There are such books as 1 and 2 Maccabees, the Wisdom of Solomon, Ecclesiasticus, books we today call the Apocrypha. There are such books as the Assumption of Moses and the Book of Enoch and several others that we call the Pseudepigrapha. There are a number of pieces of interesting literature from the Qumran community of the Essenes, such as the Manual of Discipline. Why are some of these not recognized as canonical? What is the test of canonicity?

The simple test for canonicity is inspiration. The writings that are inspired by God the Holy Spirit constitute the norm, or standard, of faith and practice. In ancient days it was its inspiration that made a book authoritative and because of this authority it was recognized as canonical. That is to say, a book did not become part of the canon because it was recognized as such. Rather, it was recognized as such because it was part of the canon by virtue of inspiration. The moment an inspired book was written it was canonical. The authors were certainly conscious of this, as is testified by their frequent use of “thus saith the Lord.” These writings were immediately held as authoritative by some, and probably deposited in the temple. But how were others to recognize which books were inspired and canonical and which were not? This was no simple question.

To say that the sole test for their recognition and acceptance was inspiration is to answer our question correctly but not completely. This simply raises another question, What is the test of inspiration?

Gleason Archer states it succinctly when he says,

The only true test of canonicity which remains is the testimony of God the Holy Spirit to the authority of His own Word. This testimony found a response of recognition, faith and submission in the hearts of God’s people who walked in covenant fellowship with Him.2

E. J. Young agrees when he says,

The canonical books of the Old Testament were divinely revealed and their authors were holy men who spoke as they were borne of the Holy Ghost. In His good providence God brought it about that His people should recognize and receive His Word. How He planted this conviction in their hearts with respect to the identity of His Word we may not be able fully to understand or explain.3

We conclude, therefore, that the books that were inspired by the Holy Spirit, and therefore were canonical, were recognized by men of faith as the Holy Spirit bore witness to the authority of these writings in their hearts.

Three crucial elements are involved in this test.

- The work of the Holy Spirit in inspiration.

- The witness of the Holy Spirit to what He has inspired and is therefore authoritative.

- The providence of God, which becomes apparent in the recognition, collection and preservation of the canonical books.

These factors constitute three basic steps.

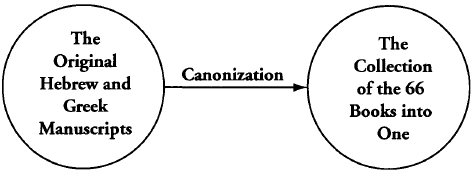

Project Number 1

- On the chart below, label the appropriate steps with the above three points.

- Match the following terms to the appropriate steps: Collection, Inspiration and Canonicity.

III. The Finished Product

To understand this process is to be equipped to cope with dozens of questions similar to those that struck down Ron. With the process firmly fixed in our minds we are ready to look at the product in the Old Testament.

The Hebrew text of the Old Testament contains three major divisions. Take a careful look at them. How do they differ from the Old Testament you know?

Law (five books):

- Genesis, Exodus, Leviticus, Numbers, Deuteronomy.

Prophets (eight books):

- Former: Joshua, Judges, Samuel, Kings.

- Latter: Isaiah, Jeremiah, Ezekiel, The Twelve (Minor Prophets).

Writings (eleven books):

- Poetry and Wisdom: Psalms, Proverbs, Job

- Rolls: Song of Solomon, Ruth, Lamentations, Ecclesiastes, Esther.

- History: Daniel, Ezra/Nehemiah, Chronicles.

What are your observations? By way of comparison, you see every one of your thirty-nine Old Testament books represented here. That is very important to note. In contrast to your Bible, however, you see only three major divisions, not four. The order of books is quite different from your Bible today. You have even seen a difference in the number of books. The combination of writings resulted in only twenty-four books. This was not the only combination that existed in ancient times. When Josephus speaks of twenty-two Old Testament sacred books, he is simply reflecting another structure or order of the same twenty-four (or, if you like, thirty-nine) books.4

In the Greek translation of the Hebrew Old Testament, the Septuagint, the books are arranged more or less topically. They fall into four divisions: the books of the law, history, poetry and wisdom, and prophecy. In general the Latin Vulgate follows the Septuagint. It is this order that has been adopted in our Protestant English Bible.

An understanding of the finished product, the Hebrew canon with its three divisions, was of critical importance to Ron. It offers tremendous leverage in defending the Bible against the kind of attack he faced. To use it effectively, however, Ron needed to know not only the facts of a threefold division in the Hebrew canon, but also the details of its formation.

IV. The Great Assembly

Although it is impossible to positively date the origin of this threefold division of the Old Testament canon, Jewish tradition dates it from the time of Ezra, attributing the work to him and the men of the Great Assembly, 520 B.C. This assembly gave way to the Sanhedrin around 300 B.C. This dates the divisions then, from about the fifth century B.C. If this is so, apparently the division was not rigidly held. The Old Testament canon is described in the New Testament as “the law and the prophets” (Luke 24:27). However, our Lord does refer to this threefold division in Luke 24:44.

The basis for this threefold division has been the object of much discussion. The first division was determined by the sole authorship of Moses. These five books constitute the “law of Moses.” He is recognized as the greatest of the prophets of Israel, the lawgiver of the nation. They were undoubtedly gathered by Joshua and regarded by the nation as the word of God from that date forward.

The second division is called the “prophets,” a title that is appropriate according to every indication of their authorship. These books were written by men with the gift of prophecy who occupied the office of prophet in the nation. As these prophets were under Moses in the administration of the nation it is appropriate that their books form the second division.

The third division comprises books of a variety of material written by men who did not occupy the official office of prophet. This explains why Daniel’s book is in the last division rather than the second one. Its position among the “writings” does not suggest a late date as many critics say. Status in that second division was based upon the official status of the authors in the nation.5

As the inspired books in the second and third divisions were written they were, by virtue of their inspiration, canonical. That is, they were authoritative. They were a standard for the faith and practice of Israel. In the providence of God and by the witness of the Spirit, these books were recognized by men of faith as authoritative. They were securely preserved in the temple precincts until the time of the Great Assembly when, under God, the twenty-four books were collected together and set in the order of the Hebrew Old Testament.

V. What Is the Point?

If you are wondering what the point of giving you all this historical data and detail, let me clear up the matter right now. We have just established that by the sixth century B.C., the Jewish community had recognized and collected twenty-four books (thirty-nine, by our count) that they regarded as authoritative. These were organized in three major divisions. They were the standard for their creed and conduct. Here was their canon.

This simple summary has the support of a host of witnesses. Consider but a few.

The earliest extant reference to these three divisions comes from the prologue of the apocryphal Ecclesiasticus. There we read, “Whereas many and great things have been delivered to us by the Law and the Prophets, and by others that have followed their steps ...” Here the authors of the third division are described as those who have followed in the steps of the prophets.

The testimony of Josephus, the first-century Jewish historian, speaks of the very thirty-nine books of our Old Testament as the corpus of Scripture “which are justly believed to be divine.” When he speaks of twenty-two books, he simply reflects a different structure of ordering the books.6

Philo, a learned Jew of Alexandria, refers to or uses as authoritative all the books of the Old Testament except five (Esther, Ezekiel, Daniel, Ecclesiastes, Song of Solomon). These are never denied, just ignored. On the other hand he never quotes nor mentions any of the apocryphal books.

Among the Dead Sea Scrolls discovered in 1947, some portion of all the thirty-nine books of our Old Testament were found. They obviously held these books in high esteem and regarded them as authoritative. Although other literature is alluded to, it is never quoted as authoritative. The books written by the Qumran sect make no claim of inspiration for themselves.7

Following the destruction of Jerusalem, Jamnia became a centre for scriptural study under Rabbi Johanan ben Zakkal. Here discussion continued concerning the canonicity of certain books that were disputed. Although the so-called Council of Jamnia (A.D. 90) was something less than a formal council, informal discussions were held that helped to crystallize and fix more firmly the Jewish tradition. It has been demonstrated that this “council” was actually “confirming public opinion not forming it.”8 Here the extent of the Old Testament canon seems to have been finally and forever settled. The same twenty-four books set in three divisions five hundred years earlier were confirmed as canonical!

Before you press on, place yourself in Ron’s position for a few moments. With the background of this chapter can you answer these questions?

Project Number 2

- In the Old Testament era did different collections exist?

- Was the collection of Old Testament books made long after the writings of those books?

- How do you know that your Old Testament contains all the inspired books of that time, and only inspired books?

If Ron’s colleague was both skilful and knowledgeable, he would still have one trump card left in his hand. It is used with devastating success over and over again against Christians who are unskilled and without knowledge.

VI. What about the Apocrypha?

Several of our new versions of the Bible include the Apocrypha. What is it? Why is it included only in some versions? Is it part of the Word of God? Answers to these questions and more come more easily when we understand that the Apocrypha is only one of the four classes of literature that emerged in the Old Testament era.

A. The Homolegoumena

These were “the acknowledged books.” Thirty-four of our Old Testament books were accepted as canonical by men of faith when they were written, and their canonicity was never disputed. They were universally and commonly acknowledged as authoritative writings inspired of God.

B. Antilegoumena

Five of our Old Testament books were “books spoken against.” They were apparently accepted immediately by believers as canonical, but at a later date were questioned as to their place in the canon. Surprisingly we have no record of any of these books being questioned until the first century A.D.

Ecclesiastes was disputed because of its alleged pessimism, Epicurianism and denial of life to come. In the light of its purpose and literary technique, these objections are not valid.

Esther was disputed because the name of God does not appear in it. This objection is offset by the spectacular manifestation of divine providence and a recognition of the peculiar purpose of the book. It is to present the fortunes of Israel in unbelief. Because they are in unbelief God withdraws from direct communication and works providentially.

The Song of Solomon was criticized because of its low morality. It speaks of physical attractiveness in rather startling and bold terms. The interpretation of Hillel, who identified Solomon with Jehovah and the Shulamite with Israel, added a spiritual dimension that helped overcome the objections.

Ezekiel was challenged on the basis of the contradiction between the description of his temple in the latter chapters of the book and the temple of Jerusalem, which had been built by Zerubbabel. This objection was met by the observation that the differences were minor and the suggestion that Ezekiel may be speaking of a future temple, as indeed he is—the millennial temple.

The objections to Proverbs were based upon several minor, apparent contradictions. For example, “Answer not a fool according to his folly” (26:4) and “Answer a fool according to his folly” (26:5).

C. Pseudepigrapha

These are religious books written under the assumed name of a biblical character such as Moses, Enoch and others. These books were written in times of national emergencies, as in the persecution of the Jews by Antiochus. Their purpose was to encourage the morale of the people. The four types of literature found in this category were apocalyptic, legendary, political and didactic. They were never recognized as canonical.

In Jude 14-16, the pseudepigrapha book of Enoch is quoted. This book of Enoch never claimed canonicity. It is, however, quoted as a true statement.

The apostle recognizes truth in this writing as we today would recognize it in a poem by Robert Frost or in the writing of C. S. Lewis. As this truth may be quoted in a sermon, so Jude found truth in the Book of Enoch and quoted it.

D. Apocrypha

Fourteen books written between 200 B.C. and A.D. 100, mainly by Alexandrian Jews, are known by the term Apocrypha, which in classical Greek means “obscure” or “incomprehensible” or “hidden.” Jerome used the word for spurious, non-canonical books.

The books fall into five classifications:

The Wisdom Books—Wisdom of Solomon, Ecclesiasticus

The Historical Books—1 Esdras, 1 & 2 Maccabees

The Religious Romances—Tobit, Judith

The Prophetic Books—Baruch, 2 Esdras

The Legendary Additions:

+Prayer of Manasseh

+Remainder of Esther

- Songs of Three Holy Children

+History of Susanna

+Bel and the Dragon

All of these are accepted by the Roman Catholic Church today, except 1 and 2 Esdras and the Prayer of Manasseh.

Although these books were not recognized by the Aramaic Targums* and the earliest Syriac Peshitta,** yet they are included in the Septuagint—the Greek translation of the Old Testament by the Alexandrian Jews. Does the presence of the Apocrypha in the Septuagint indicate they were recognized as canonical?

Not necessarily. Several points ought to be noted.

- The manuscript evidence is uncertain. Vaticanus lacks 1, 2 Maccabees, includes 1 Esdras. Sinaiticus lacks Baruch, includes 4 Maccabees. Alexandrius contains 1 Esdras, 3 and 4 Maccabees. “Thus it turns out that even the three earliest manuscripts of the LXX show considerable uncertainty as to which books constitute the list of Apocrypha, and that the fourteen accepted by the Roman church are by no means substantiated by the testimony of the great uncials of the fourth and fifth centuries.”9 The first point to be noticed, then, is that there never was a definite canon of the Septuagint.

- Philo, the Alexandrian historian, never quotes from the Apocrypha. This is surprising because he lived in the city of the Septuagint, which included it.

- The discoveries at Qumran, where some apocryphal books and pseudepigraphic*** books have been found, along with books accepted as canonical, demonstrate that “subcanonical books may be preserved and utilized along with canonical books.”10 Therefore the presence of the Apocrypha in the Septuagint does not necessarily imply that believers recognized it as canonical.

- The Septuagint was the Bible of our Lord and the early church. Yet never did our Lord or the writers of the New Testament quote from the apocryphal books that were interwoven through the Bible they used. Never did they indicate any recognition of authority in these books.

- Aquila’s Greek Version of the Old Testament (A.D. 128) did not contain the Apocrypha and yet was accepted by the Jews of Alexandria.

- In his Latin Vulgate, Jerome included the Apocrypha but did not recognize it as canonical. He pleaded for the recognition of only the Hebrew canon, excluding the Apocrypha.

- Meliot, Justin Martyr, Origen, Tertullian, Gregory the Great (640), Cardinal Ximenes and Cardinal Cajetan (1534) all rejected the canonicity of the Apocrypha.

|

* Aramaic Targums—Aramaic paraphrases or interpretations of some parts of the Old Testament. ** Syriac Peshitta—The Syrian translation of the Old Testament Scriptures. Peshitta = “simple.” A simple translation. ***Pseudepigraphic books—These were other Jewish writings that were excluded from the Old Testament canon and from the Apocrypha.

|

However, in 1546, at the Council of Trent, the Roman Catholic church decreed the Apocrypha to be “Sacrosancta.” “At one of the prolonged sessions, with only fifty-three prelates present, not one of whom was a scholar distinguished for historical learning, the decree ‘Sacrosancta’ was passed, which declared the Old Testament including the Apocrypha are of God.”11 In so doing Rome disregarded not only the testimony of history, which generally rejected the Apocrypha, but also the role of the church councils, which up to this point had only confirmed the opinion of people. These councils never formed public opinion, they only confirmed it. Why were such precedents neglected? Some historians think Rome was motivated by political reasons. In the wake of the Reformation she needed to reassert the authority of the church.

Merrill F. Unger offers a helpful survey of the history of the Apocrypha since 1546.

The Church of England (1562) followed Jerome s words, “The Church doth read ... (the Apocrypha) for example of life and instruction of manners; but yet doth it not apply them to establish any doctrine.” The view of the Westminster Confession would logically banish them from the Bible altogether. “The books commonly called Apocrypha, not being of divine inspiration, are not part of the canon of Scripture; and therefore are of no authority in the Church of God, nor to be otherwise approved and made use of than other human writings.” This view may be said to have prevailed in Protestantism.

Beginning in 1629, the Apocrypha were omitted from some editions of English Bibles. Since 1827, they have been excluded from practically all editions. In the Revised Version (1885) and the American Standard Revision (1901), they were omitted entirely. In 1895, they were revised and published in a separate volume.12

In the ecumenical climate of our day, the Apocrypha is becoming increasingly popular and is included in many translations of the Bible. For example, the New English Bible and the Oxford Annotated Bible include it. Should the Apocrypha be regarded as inspired and occupy a place in the canon of Scripture? For several reasons we think not.

1. Not one of the apocryphal books was at any time included in the Hebrew canon.

2. Not one is ever quoted in the New Testament. This is truly amazing because they were included in the Septuagint—the Bible of the apostles! The Greek Bible (in its extent) was not the Bible of the Lord and disciples. Although they used it, they did not use it all! It is not entirely clear whether the prophecy attributed to Enoch in Jude 14 is a reference to the Enoch of Genesis 5 or to a similar statement in the Book of Enoch (1:9). If it is from the Book of Enoch, it is important to note that it is not from an apocrypha book, but rather from the pseudopigrapha books (see p. 99). Furthermore, the book never claimed canonicity and was never recognized as canonical. As Paul quoted a Cretan poet in Titus 1:12 so Jude quotes something as true from the book of Enoch.

3. These books do not claim to be the word of God. As a matter of fact Maccabees denies he is a prophet. Upon at least three occasions (1 Macc. 4:46; 9:27; 14:41) he indicates that the current feeling in Israel was that there was no prophet available for consultation. He recognized that the spirit of prophecy had long since departed.

4. The testimony of Josephus indicates that the Jews believed the Old Testament canon to be closed and the gift of prophecy to have ceased in the fifth century B.C. In his Contra Opionem Josephus writes:

From Artaxerxes (the successor of Xerxes) until our time everything has been recorded, but has not been deemed worthy of like credit with what preceded, because the exact succession of the prophets ceased. But what faith we have placed in our own writings is evident by our conduct; for though so long a time has now passed, no one has dared to add anything to diem, or to take anything from them, or to alter anything in them.13

Here Josephus reflects the minds of the first century Jews and says no canonical writings have been composed from the time of Artaxerxes, which, by the way, was the time of Malachi.

5. The quality and doctrine of the Apocrypha is very inferior to that of the canonical books. It has well been pointed out that

both Judith and Tobit contain historical, chronological and geographical errors. The books justify falsehood and deception and make salvation to depend upon works of merit. Almsgiving, for example, is said to deliver from death (Tob. 12:9; 4:10; 14:10, 11).

Judith lives a life of falsehood and deception in which she is represented as assisted by God (9:10, 13). Ecclesiasticus and the Wisdom of Solomon inculcate a morality based upon expediency. Wisdom teaches the creation of the world out of pre-existent matter (11:17). Ecclesiasticus teaches that the giving of alms makes atonement for sin (3:30).

In Barach it is said that God hears the prayers for the dead (3:4), and in I Maccabees there are historical and geographical errors.14

This is not to say the Apocrypha is of no value. Although they are not Scripture, the books are of “considerable antiquity and of real value. They, like the Dead Sea Scrolls, are monuments to Jewish literary activity of the intertestamental period.”15 They show the lack of idolatry, the solid monotheism and the presence of a Messianic hope in the period between the Testaments. Also, they trace the heroic political struggles of Israel for liberty.

The material of this chapter is part of the very material I put into the hands of my anxious friend Ron. But it is only part. There still remains those gnawing questions about the New Testament that call for an answer. It is amazing how an experience like his in that teachers’ lounge sharpens one’s appetite for this kind of information! Armed with some facts, Ron was able to “return to the scene” and “contend for the faith.” And this is the calling of every believer.

Review

In this chapter we have established a definition for the term “canon” and have studied the test, the divisions and the extent of the Old Testament canon. Have you grasped the key points? Why not test yourself now? Go back to the questions at the beginning of our chapter and measure your retention. You ought to be able to answer every one of them now.

For Further Study

- Study carefully Jude 14-16. What is the problem here? How can it be answered?

- Discuss the liberal theories as to the origin of the Old Testament canon. See: Gleason Archer, A Survey of Old Testament Introduction, (Chicago, IL: Moody Press, 1964), pp. 70-72.

- Explain and refute the documentary theory of the Pentateuch. See again Gleason Archer, A Survey of Old Testament Introduction, chs. 6-8.

Bibliography

Archer, Gleason. A Survey of Old Testament Introduction. Chicago, IL: Moody Press, 1964.

Beckwith, Robert. The Old Testament Canon of the New Testament Church. Grand Rapids, MI: Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing Co., 1985.

Harris, Laird. Inspiration and Canonicity of the Bible. Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan Publishing House, 1969.

Harrison, R. K. Introduction to the Old Testament. Grand Rapids, MI: Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing Company, 1969.

Henry, Carl F. H. (ed.). Revelation and the Bible. Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Book House, 1958.

Unger, Merrill E. Introductory Guide to the Old Testament. Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan Publishing House, 1964.

Van Campenhausen, Hans. The Formation of the Christian Bible. Philadelphia, PA: Fortress Press, 1972.

Waltke, Bruce. “How We Got Our Old Testament,” Christian History, Vol. XIII, No.3, Issue 43, pp. 32, 33.

1 Dr. S. L. Johnson, Jr., “New Testament Introduction” (Unpublished class notes, Dallas Theological Seminary, 1966).

2 Gleason Archer, A Survey of Old Testament Introduction (Chicago, IL: Moody Press, 1964), p. 69.

3 E. J. Young, “The Canon of the Old Testament,” Revelation and the Bible, ed. Carl EH. Henry (Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Book House, 1958), p. 168.

4 Laird Harris, Inspiration and Canonicity of the Bible (Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan Publishing House, 1969), p. 141.

5 Gleason Archer, A Survey of Old Testament Introduction, pp. 368, 369.

6 Laird Harris, Inspiration and Canonicity of the Bible, p. 141.

7 Ibid, p. 137.

8 R. K. Harrison, Introduction to the Old Testament (Grand Rapids, MI: Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing Company, 1969), p. 278.

9 Gleason Archer, A Survey of Old Testament Introduction, p. 66.

10 Ibid., p. 66.

11 Merrill F. Unger, Introductory Guide to the Old Testament (Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan Publishing House, 1964), p. 106.

12 Ibid., p. 107

13 Gleason Archer, A Survey of Old Testament Introduction, p. 63.

14 E. J. Young, “The Canon of The Old Testament,” pp. 167, 168.

15 Laird Harris, Inspiration and Canonicity of the Bible, p. 180.

Related Topics: Bibliology (The Written Word), Canon, History