7. Jeremiah

Related MediaNotes on the Book of Jeremiah

I. The Historical Era of Josiah (640-609 BC)

Little Josiah became king of Judah at the age of eight. His father, Amon, had been assassinated at the age of 24 after two years of rule. Amon had followed the religious lifestyle of his father, Manasseh, who ruled long (55 years) and lived wickedly. In spite of a repentant attitude in his last years after having been defeated and deported by the Assyrians to Babylon,1 Manasseh left a legacy of rebellion against the Lord made worse by the length of his reign. In God’s sovereignty this wicked work was to be countered by the godly young prince who acted first under tutors and later on his own to restore godly practices in Judah.

In his eighth year (632) he began “to seek the God of his father David” (2 Chron 34:3). In his twelfth year (628) at the age of twenty, he began the reform movement that was to prove so successful. During this purge, Chronicles tells us, he went into the cities of Manasseh, Ephraim, Simeon and Naphtali and tore down their images. This is Assyrian territory. It could be that religious activity would be tolerated on the part of a Judean King (as messengers of Hezekiah had gone north to announce the great Passover), but this activity is too blatant for anything that mild. This must indicate some effort on the part of Josiah to extend political control as well. Jeremiah received his call to the prophetic ministry one year later in 627. Ashurbanipal died in 626 or two years after the beginning of the reform movement complaining of all the misery and misfortune that had befallen him.

Internal troubles resulted in succession squabbles. Ashur‑etil‑ilani, Ashurbanipal’s heir apparent, had to fight for the throne. Babylonia, until now a province of Assyria, broke away under the Chaldean Nabopolassar in 626 when Ashurbanipal died and began fighting Assyria upon Nabopolassar’s accession in 625.

An even more extensive reform was carried out in Josiah’s eighteenth year (622) during which the law book was found that called for even greater repentance. He again made a foray into the north, tearing down the altar built at Bethel by Jeroboam. He also removed all the houses of the high places that were in the cities of Samaria. A great Passover was held, but except for a passing comment (2 Chron. 35:18), there is no mention of participation by the northern Israelites. The confusion going on in Assyria prevented effective control of the Assyrian territory of Samaria and allowed Josiah to move somewhat at will.

II. The Man, Jeremiah

Jeremiah is better known than most prophets because of the many biographical sections in the book. We have greater insight into his personality, his struggles and his commitment to the Lord who called him than in any other OT prophet.

Jeremiah was born in the village of Anathoth north of Jerusalem and was the son of Hilkiah who was a priest. This priestly family was probably descended from Abiathar whom Solomon banished to Anathoth because he supported Adonijah (1 Kings 2:26). Jeremiah was apparently young when he was called (1:6). His ministry spanned forty years from the thirteenth year of Josiah to some time after the destruction of Jerusalem in 586 BC2

III. The Milieu

This historical background given above describes the situation in which Jeremiah ministered. He began in the thirteenth year of Josiah’s reign and so shared in the early period of reform. With Josiah’s death, Jeremiah’s ministry became increasingly difficult, since there was no support from the throne. In spite of the fact that his early prophecies proved true, he was still treated roughly when he tried to turn the minds of the officials, priests and people to the Lord and to get them to submit to inevitable adversity under Nebuchadnezzar.

IV. The Call Theme in Jeremiah

When God calls Jeremiah to the prophetic ministry, he tells him there will be six negative and two positive components in his message: to tear down, destroy, pluck up, and root out and to build and to plant (1:10). These phrases are reiterated in full or in part several times in the book. At least four of the words appear in 1:10; 18:7,9; 24:6; 31:28; 42:10. Between one and three occur in 12:14-17; 31:4,5; 31:40; 32:41; 33:7; 45:4.

V. The Text of Jeremiah

The LXX text of Jeremiah is one eighth shorter than the Hebrew text underlying our English translations. In addition there is somewhat of a different arrangement of material (e.g., the oracles against the nations are situated in a different place than in the MT). Qumran fragments support a reading unique to the LXX and lead to an inference that there was a Hebrew Vorlage (or underlying text) for the Greek translation. But we must stress that it is only an inference since all we have are a few fragments (4QJerb).3 I believe we must deal with these differences as text critical problems (some want to talk about a developing canon, but canon speaks of the book, whereas textual criticism speaks of the changes in the text.)

VI. The Structure of the Book of Jeremiah.4

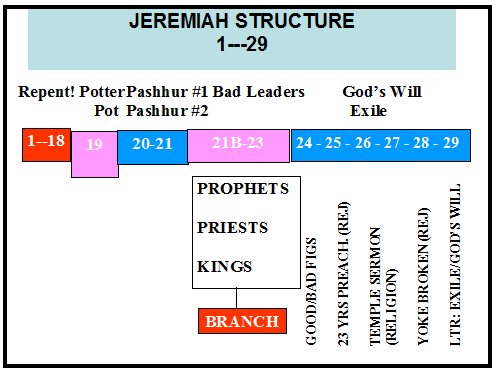

A. Chapters 1—29

1. It seems that Jeremiah wants us to understand that the Judeans had ample opportunity to repent and thus avoid subjection. This is especially illustrated in the temple sermon (chapter 7) and in chapters 17-18. In the potter imagery, the nation that chooses to repent will avoid reshaping in judgment. God will change his mind about the plans for that nation.

2. Moving from the potter in chapter 18 to the pot in chapter 19 is an abrupt change. The smashed pot indicates that judgment is inevitable. Even if they were to repent now, they would only preserve their lives. Submission to Babylon is now unavoidable.5

3. Chapters 20 and 21a are to be viewed together. Chapter 20 represents official rejection of Jeremiah. Pashhur ben Immer persecutes Jeremiah and denies his message. However, chapter 21 (from after 588 or several years later) shows that Jeremiah’s message was fulfilled when another Pashhur (ben Melchiah) entreats Jeremiah to pray for the city, (now under siege by Babylon).

4. Chapters 21b-23 introduce a new element: the leaders of Israel have failed in their responsibility and Judah has suffered. First it is the kings and finally it is the prophets. But in between is the marvelous message of hope of a coming Branch. As in Isaiah, this ideal king will judge with equity and will deliver the people of God.

5. Chapter 24 teaches that the Jews who went into exile in 597 are the good figs, not in the sense that they are more moral, but that God’s purpose has been fulfilled.

6. Chapter 25 is a recap of the twenty-three years of preaching, showing that there was ample opportunity to repent, but that the people refused to do so.

7. Chapter 26 is an abbreviation of the temple sermon of chapter 7 with the addition of the persecution and threat of death to Jeremiah. This again shows that there was a clear offer of repentance and avoidance of judgment, but it was rejected.

8. Chapter 27 is the yoke chapter. The Judeans no longer have the option of avoiding subjection, their only option now is to submit to Nebuchadnezzar’s yoke. The alliance into which Zedekiah is entering is futile because it is not the will of Yahweh.

9. Chapter 28 is the breaking of the yoke by Hananiah, illustrating the official rejection of Jeremiah’s message. His judgment for doing so is death.

10. Chapter 29 is a letter to the exiles urging them to accept Yahweh’s will and settle down. The false hope raised by the prophets will only bring pain. They will be there seventy years.

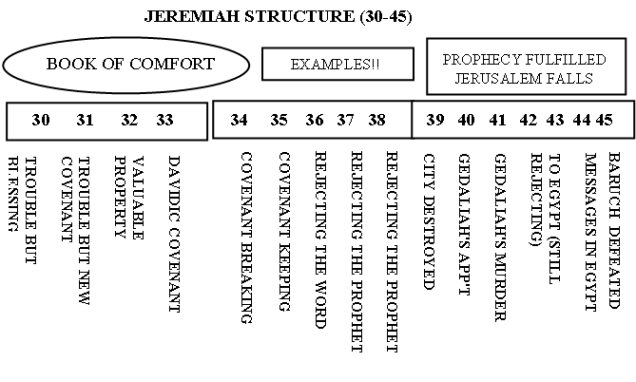

B. Chapters 30—45

1. Jeremiah 30-33 is one of the clearest units in the book. Here the prophet has collected messages preached over some period of time containing messages of hope and consolation. They are placed here to show that in spite of the judgment of God brought upon his people, that there is still a future for Israel. The New Covenant, especially, gives great hope for the future of Israel. The context clearly calls for the seed of Abraham to be restored in the Eschaton. Chapter 32 is a historical account, but it is in the section on hope, because Jeremiah is instructed by Yahweh to buy a piece of land while the city is under siege! This teaches that the “real estate” will again prove to be valuable. Chapter 33 harks back to the Davidic Covenant and shows that the “Branch” spoken of in chapter 23 will rule and reign in equity and justice.

2. Chapters 34-38 are a series of “Examples” of why the Judeans had to go into exile. Chapter 34 shows how the covenant of God was broken (on the freeing of slaves) and even the covenant they had made was broken. Chapter 35 is an example of people who kept the covenant of their ancestor, Jonadab, and thus shamed the Judeans. Chapter 36 is an example of the king of Judah flagrantly rejecting the word of God by burning it in the fire. A contrast is being drawn with the response of Josiah to the scroll of the law and that of his son Jehoiakim to the scroll of the prophet. Chapters 37-38 provide two examples of the rejection of God’s spokesman, Jeremiah. In 37 he is called a traitor and in 38 he is put into the pit to die.

3. We come back to a historical unit in chronological order in chapters 39-44. All the prophecies of Jeremiah about the fall of the city are fulfilled. The people continue to reject the word of the prophet even though he has been fully vindicated as a true prophet of Yahweh. They go to Egypt after the violent death of Gedaliah and Jeremiah

continues to prophesy in the Delta region. It was presumably sometime after this in Egypt that Jeremiah and Baruch compiled his messages of the previous forty or so years.

4. Chapter 45 is in a unique position. The time of the prophecy is 605 when Jeremiah wrote the scroll that Jehoiakim burned (chapter 36). Why is it placed last? It forms an appendix, much as do the oracles against the nations (46-51). I am treating it as a negative conclusion: Jeremiah and Baruch are called upon to preach to a God-rejecting people. Their task will not be easy. In the traumatic experience of chapter 36, Baruch became discouraged with the task. God tells him through Jeremiah not to be discouraged. I suspect this chapter stands here to say, “All the prophetic ministry of Jeremiah from 627 to 586 and afterward was rejected, but God’s purposes will none-the-less stand. Therefore, Baruch must not be discouraged.”

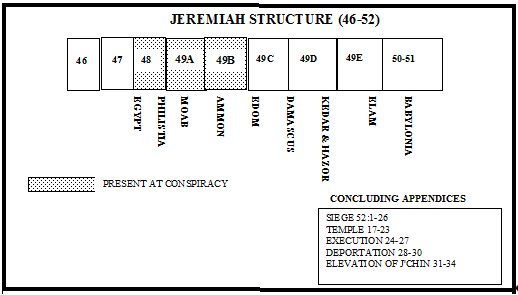

C. Chapters 46—52

1. Jeremiah gave various oracles against several nations in the course of his ministry. Chapter 26 is a good example of one of those oracles. There Jeremiah is told to make the nations drink the wine of God’s wrath. Those nations include: Judah, Egypt, Uz, Philistines, Edom, Moab, Ammon, Tyre, Sidon, Dedan, Tema, Buz, Arabia, Zimri, Elam, Media, Kings of the North, Sheshach (Babylon). As a matter of fact, chapters 46-51 are placed after the middle of 26:13 in the Septuagint. In the Hebrew text, they are treated as an appendix at the end of the book.

2. Egypt is the first nation to receive an oracle and Babylon is the last. As in Isaiah, God wants His people to understand that He is in charge of the universe and determines the events and outcomes of all peoples. Egypt, at first an enemy but later an ally, is shown in 605 BC to be under God’s judgment, for Babylon will defeat her at Carchemish. But Babylon, the nemesis of all nations and God’s servant for judgment, will one day in turn be judged. Some of the material comes from after 586 and reflects the exile. From that exile, God will deliver his people and judge Babylon. Likewise all the other nations will be defeated sooner or later. Therefore, the puny plans of man are a waste of time.

3. Finally, chapter 52 is an appendix to show the ultimate outcome of all God’s work concerning his people Judah. The city and temple were destroyed, the leadership was judged by Babylon for rebelling, people were taken into captivity, and finally, even the king in exile, Jehoiachin was elevated by Evil Merodach (Ewal Marduk) in 560 BC Thus the skein of prophecy is spun out. God’s purposes have triumphed over all the plans of man. Ultimately, Judah will be restored both in 539 and in the Eschaton. Then God’s plans for Israel will be joyously fulfilled.

VII. Outline Notes

The outline of Jeremiah is difficult because the book is not constructed chronologically. Consequently, events are out of order.6 The messages of Jeremiah were brought into a continuous whole some time after the last one had been delivered. The sermons and speeches delivered at different times and under different circumstances over some thirty years, have been brought together in this final form with a message: Judah deserves to be punished. Had she repented in the earlier years, the punishment could have been averted. However, with the passing of time and the hardening of hearts, the captivity became inevitable. As a completed whole, the book of Jeremiah is an apologetic for God’s action against and in behalf of His people. The argument of the book progresses from the call of Jeremiah in chapter 1 to the removal to Egypt after his message had again been rejected in chapter 43.

A. Undated prophecies and events showing that Judah had ample warning to repent (1:1—17:27).

1. Jeremiah is called to the prophetic ministry and given a message to preach to Israel (1:1‑19).

The historical note is given on Jeremiah’s ancestry and indicates that he prophesied from the thirteenth year of Josiah (627 BC) until the eleventh year of Zedekiah (586 BC). We know that he also prophesied some time after the fall of the city and was taken to Egypt (1:1‑3).

God sovereignly called Jeremiah to be a prophet before he was even born. In response to Jeremiah’s protestations that he is too young, (naar, נַעַר), God promised to be with him. In spite of that promise, Jeremiah suffered greatly, yet God was with him throughout his ordeal.

The message of Jeremiah is given in 9‑19. He is “to root out, pull down, destroy, throw down, build and plant.” There are four negative issues and two positive ones. Watch for these to recur throughout the book (1:9‑10).7

Through two symbols God promises to bring judgment on Judah. The first is an almond rod (shaqed, שָׁקֵד). By a pun on the word the Lord says, “I will hasten (shoqed, שׁקֵד) my word to do it.” The second symbol is a seething pot with its opening toward the north. This indicates that God is going to call the nations of the north against Judah8 (1:11‑16).

Jeremiah is now told to gird himself up and begin prophesying. Kings, princes, priests and people will resist him. Yet God promises that he will prevail over them all (1:17‑10).

2. Jeremiah pleads with backslidden Judah to repent (2:1‑37).

Looking back to the wilderness experience as a time in the early history of Judah, God reminds them of His devotion to her. Israel was like the firstfruits that belong to the Lord. Anyone who interfered with her became guilty (2:1‑3).

The Lord asks them what He has done that they are finding fault with Him. He points out that the priests are not asking “Where is Yahweh”; those who handle the law are not knowing Him; the rulers transgress against Him; and the prophets are prophesying through the pagan god Baal (2:4‑8).

The Lord enters a court case with them again (riv, רִיב). He calls on all the witnesses of foreign countries to find if anyone has ever left their gods as Judah as left her God. Not only have they forsaken Him, the fountain of living waters, but also they have hewn out cisterns for themselves (2:9‑13).

“Israel” here refers to the northern kingdom that went into exile shortly after Jeremiah began prophesying (722 BC). The “you” refers to Judah who has suffered at the hands of Egypt (this must reflect a period early in the reign of Jehoiakim rather than Josiah). She goes to Egypt and Assyria (looking for gods), but they have forsaken the Lord (2:14‑19).

Judah’s apostasy is reflected in the imagery of an ox that refuses to serve under the yoke; as a choice vine that refuses to produce fruit; as a stained person who cannot be cleaned with the strongest detergents; and as a wild donkey in heat who pursues her lovers (2:20‑25).

Judah, says God, is ashamed of her idolatrous practice. The word shame (bosheth, בּשֶׁת) often has the connotation of embarrassed, that is, they let Judah down in a time of need. God demands that Judah call on her idols for deliverance if she believes they can help her. There are as many gods as there are cities in Judah9 (2:26‑28).

The Lord insists that they tell Him why they are contending with Him. He has struck them, but it has not helped. It is not normal for people to forget God, but they have forgotten their God. They were committing the same sins condemned a century before by Amos, Hosea and Isaiah, yet they refused to admit their sin. The historical situation may refer to Assyria prior to 609 when Josiah may have been trying to work out an arrangement with Assyria, but she fell to Babylon. Now they seem to be going to Egypt for help against Babylon (2:29‑37).

3. God appeals to His adulterous wife to repent (3:1—4:4).

The NASB has construed the literary structure of chapter 3 as a composition containing poetry (1‑5, 11‑14, 19‑23) and prose (6‑10, 15‑18, 24‑25).10 The critics will argue that the prose sections are later “deuteronomistic” additions to Jeremiah’s poetic preaching. Thompson argues that like Shakespeare, Jeremiah could have written both prose and poetry.11 The difference in style may show that Jeremiah preached these passages at different times and later edited them into a continuous whole. The unity of the passage is shown by the concept of divorce (3:1 and 8), “returning” or “turning” (shub, שׁוּב: 3:1,1, 7, 7, 10, 12, 14, 14, 19, 22, 22), and calling God “Father” (3:4 and 19).

The Lord appeals to the Deuteronomic law against a husband divorcing his wife and later taking her back again (Deut. 24:1‑4). Since that is the law, would it not be improper for Yahweh to take Israel back after she has committed adultery? The phrase “Yet turn to me” is debated (veshob ’eli,וְשׁוֹב אלִי ). Does it mean, as NASB implies, “since you have committed adultery, do you think you can return to me?” Or is it be taken as an imperative, “Yet [in spite of this] return to me!” God most assuredly will take Judah back as a demonstration of His grace (cf. Hosea 1‑3, Isa. 50:1), but only when there is genuine repentance and not the superficial response recounted in this chapter. If Judah will sincerely repent, He will override His Deuteronomic law in His dealings with Israel (3:1).

Jeremiah charges them with extensive idolatry. He likens them to an Arab sitting along the road. As a result God has withheld the former rains (showers: Oct/Nov) and the latter rains (spring: Mar/Apr). In spite of this Judah is brazen like a harlot and refuses to be ashamed. Under pressure, they have called God “Father” and “friend” ; they have prayed that He would not be forever angry. But in spite of this speech, they have done all the evil they were able to do (3:2‑5).

Yahweh compares Judah to her sister Israel and says that Israel comes off looking better. He cries out to Israel to return to Him because He is gracious. He promises to return them to Zion (3:6‑14).

The promise of a return brings Jeremiah to the message on the shepherds whom God will raise up to them (cf. chapter 23); Yahweh speaks of His new covenant which will not need the ark; He speaks of Jerusalem as the “throne of the Lord”; and finally He speaks of the unity that will exist between Israel and Judah (3:15‑18).

Jeremiah returns to poetry to appeal further to Israel who has now been judged and sent into exile. God’s desire is to set them as sons in his pleasant land, but they have departed from Yahweh like a treacherous wife. The result is “weeping and supplication” because of their captivity. The “hills” (other countries) cannot help them; only Yahweh can be the salvation of Israel. Verses 24‑25 are construed as poetry in BHS and Thompson, but as prose in NASB. These verses constitute a confession for Israel acknowledging their sin. Some would argue that these verses might address Josiah’s attempts to extend the reform into the north (2 Kings 23:15‑20). In any event they reflect the deep concern of Jeremiah for the Northern Kingdom and his expectation of their restoration with Judah (3:19‑25).

Yahweh appeals to Israel to return with the promise that the blessings of the Abrahamic covenant will be theirs (nations will bless themselves in Israel: hithbareku, הִתְבָּרְכוּ). To Judah and Jerusalem He also appeals for repentance. They are urged under the similes of sowing and circumcision to repent so that God’s wrath might not break out on them (4:1‑4).

4. Yahweh promises destruction of Judah (4:5—6:30).

Yahweh tells Judah to prepare for war by going into the fortified cities because He is going to bring devastation from the north (this of course refers to Babylon) that will lay the land of Judah waste. The mind of the king, princes, priests and prophets will be astounded (4:5‑9).

Jeremiah’s statement in 4:10 is startling. The direct, stark statement to God sounds blasphemous until we get to understand Jeremiah and realize that he had an intense and close relationship with his Lord. As such he poured out his anguished heart on more than one occasion. Who is telling Judah she will have peace? It can only be the false prophets who continuously speak a lie in the face of Jeremiah’s predictions (6:14; 14:13; 23:16‑17). “Throat” is the translation of nepesh (נֶפֶשׁ) which normally means “soul” or “life.” The meaning of “throat” is attested in Ugaritic (4:5‑10).

In spite of the word of false prophets, God promises to come against Judah in judgment. This statement is in the first person, but the prophet adds another verse in the third person to say that God will come against Jerusalem in chariots like a whirlwind (4:11‑13).

Yahweh appeals again for repentance and promises judgment from the north to punish them for their sin (4:14‑18).

Jeremiah is known as the “weeping prophet,” and these verses support that identification. Jeremiah laments the destruction of his people. At no point did Jeremiah take delight in the destruction of his people in spite of the way they treated him. To Jeremiah’s lament is appended a statement of Yahweh that His people are foolish. Perhaps this is God gently chiding Jeremiah with the truth that the judgment is deserved (4:19‑22).

Jeremiah in a series of “I looked” statements (raithi, רָאִיתִי) speaks of the devastated earth that Yahweh is going to judge (4:23‑26).

Yahweh responds by saying that He will indeed bring devastation upon Judah, and yet, He promises that it will not be a complete devastation. Furthermore, Judah will not be able to allay the judgment by primping. She will be despised by her lovers and will cry out in distress (4:27‑31).

The reason for the judgment is amplified by the analogy of Sodom and Gomorrah. If Yahweh can find anyone truly faithful in Jerusalem, He will spare Jerusalem from judgment. On the contrary, they have refused to repent (5:1‑3).

Jeremiah intercedes for the people by arguing that the poor do not understand the way of the Lord. He expects the great ones (the leaders) to be responsive, but they have broken the yoke of their obedience to Yahweh. As a result judgment must come upon them (5:4‑6).

Yahweh argues that there is no basis for forgiveness since they refuse to repent and carry out the fertility practices in real life (5:7‑9).

God says that the branches of sin are to be removed from His vineyard. Both houses of Israel have lied by denying that God could ever judge them for their sin. Consequently, the words of Jeremiah are going to be like a fire as he prophesies the coming of a powerful, ferocious nation to destroy them.12 An addendum is given again that God’s judgment will not be final. There is hope, but only after they have served strangers in a land not theirs (5:14‑19).

Yahweh speaks in terms that we have seen before in His prophets. He is the creator, the one who sets the boundaries of the sea, brings rain, appoints seasons and otherwise shows Himself to be the sovereign God. Yet Israel has turned against Him and refuses to live righteously. Consequently, they must be judged. To compound the egregious nature of their sin, the prophets are false, the priests ignore God in their activity, and the people like it this way (5:20‑31).

The motif of the sounding of the trumpet is given again (cf. 4:5ff). The destruction from the north is again promised. Judah will be devastated so that shepherds will graze their flocks there. The reason for this siege is that Jerusalem maintains wickedness and refuses to let go of it (6:1‑8).

Under the imagery of grape pickers, God says that the remnant of Israel will be gleaned. The command of 6:9 was probably directed to Jeremiah. God is telling him to preach again to what is left in case he has missed someone. Jeremiah complains that there is no one else left to whom he could speak who would respond to his message. Israel in this context must refer to the people of God in general and not to the northern kingdom. Jeremiah indicates weariness with being rejected when he preaches Yahweh’s message, and he calls upon God to carry out His judgment. God’s response is melded into Jeremiah’s statement. He says He will indeed judge the people because they live wickedly. The prophets will be judged because they are crying “Peace” when judgment is coming (6:9‑15).

God cries out for the people to obey Him, but they refuse. He sets a watchman (prophets) but they refuse to listen, He blows the trumpet, but they refuse to hear it. Therefore He will judge them. Jeremiah picks up the theme already heard in Amos, Hosea and Isaiah that empty ritual will have no impact on God. Their sacrifices are not pleasing to Him (16‑21).

The foe from the north is again presented. This description of a fierce people could refer to most any nation in those days, since war was conducted without quarter by all those practicing it who had the ability to do so (6:22‑26).

This section on the coming judgment of God is closed with Yahweh’s statement to Jeremiah under the simile of an assayer or one who tests metals. Jeremiah’s job is to test the character of people to see how they will respond and to separate the dross from the real metal. Unfortunately, they refuse to respond, and so are considered by God to be “rejected silver,” in other words all dross. As a result, God has rejected them (6:27‑30).

5. Jeremiah delivers his famous temple sermon (7:1‑8:3).

Jeremiah attacks the religiosity of the people because they were taking refuge in a superficial response to Yahweh possibly brought about forcibly by Josiah. They were mixing worship of Yahweh with worship of Baal and other deities. “Jeremiah not only had to stand against their wickedness, he had to stand against their righteousness.”13

a. Judah has a misplaced confidence (7:1-7).

This sermon is entirely in prose, which leads critics to argue that it is not typical of prophetic preaching style. Why does this need to be true? At best they may be right in assuming it was put in this form (I would say by Jeremiah) after it had been delivered orally. The people are coming into the temple to worship Yahweh. Jeremiah preaches his sermon to them because they are assuming that the presence of the temple (The temple of the Lord, the temple of the Lord, the temple of the Lord) will prevent judgment from coming on them. However, God says that judgment may be averted only by repentance.

b. Judah practices hypocrisy (7:8-16).

Yahweh says that Judah is breaking commandments 8, 6, 7, 9, and above all number 1 and still has the audacity to come to the temple and claim that Yahweh has delivered her. They should go to Shiloh where the tabernacle was first pitched to see what happened to it. Shiloh was apparently destroyed in the Philistine attacks that captured the ark.14 If the tabernacle from God’s wrath did not protect Shiloh, what makes Jerusalem think she is safe because the temple is there? God will judge them for their sins.

c. Judah practices idolatry (7:16-20).

This section is not part of the original sermon since God admonishes Jeremiah not even to pray for these people because they refuse to listen and are involved in idolatrous practices. Yahweh tells Jeremiah to take note of what Judah is doing in the streets of Jerusalem. The entire family is involved in the worship of the astral cult Queen of Heaven (malkath hashamaim, מַלְכַּת הַשָּׁמַיִם). A full quote from Thompson will help us understand the issue. “In the cities of Judah and in the streets of Jerusalem the cult of the Queen of Heaven was being practiced. The reference is to the Assyro‑Babylonian Astarte (Ishtar, cf. 44:17). The worship of Astarte along with other Mesopotamian gods was popular in Judah in the days of Manasseh (2 K. 21; 23:4‑14). In Mesopotamia this goddess was known precisely as the Queen of Heaven (sarrat same) or the Mistress of Heaven (belit same). The name was still in use in the fifth century BC in Egypt, as the Aramaic papyri from the Jewish colony at Elephantine testify. Astarte was an astral deity, and her worship was practiced in the open (19:13; 32:29; cf. 2 K. 23:12; Zeph. 1:5). There were local expressions of her cult in Mesopotamia, Canaan, and Egypt. Perhaps, indeed, the cult of Astarte was identified with that of some Canaanite goddesses.”15

d. God speaks of His true revelation (7:21-28).

When God first spoke to the people of Israel, He gave the decalogue and the people agreed to accept it and follow it. At that time God did not speak of ritual—that would come later. Therefore, Judah should recognize that the ritual is secondary to what Yahweh really wants: obedience. On the contrary there has been disobedience from the very beginning. God now says that He will not answer them when they pray.

e. God gives a final promise of judgment (7:29-8:3).

The people are told to enter into the mode of mourning because God is going to judge His people. Topheth is in the valley of Hinnom where Judah practiced child sacrifice. God will turn that place into the “valley of slaughter” when He brings judgment on Judah. It is considered disgraceful for a body to be disinterred and the bones scattered.16 When God brings judgment on Judah, the bones of all the leaders will be scattered, and death will be chosen over life at that time.

6. Through a series of first person statements, Yahweh charges Judah with her sin (8:4—9:26).

Judah in her conduct goes against all natural laws. When one falls, he gets up. The stork knows her seasons, etc., but Israel does not have enough sense to know the ordinance of Yahweh (8:5‑7).

Judah considered herself to be wise, but Yahweh says that the wise men are a disappointment because they have rejected the word of Yahweh. Because of this, Yahweh will judge them. Everyone is greedy; even the prophet and the priest are involved. The only message they bring is Shalom when in reality there is no Shalom. Therefore, they will be punished (8:8‑13).

A confession is written for Judah to say: “We must prepare for judgment for we have sinned against Yahweh” (8:14‑17).

Jeremiah speaks for himself and almost for Yahweh in his lament for the people of Judah because of the suffering that is going to come upon them. There is no healing for His people (8:18‑22).

Jeremiah’s lament goes on in chapter 9. Again he speaks for himself and for Yahweh. He wishes he could get away from the people because of their sinfulness. Yahweh laments that they do not know Him (9:1‑6).

Because of their sin Yahweh is going to refine them and assay them as metal (cf. 6:27‑30). What He finds is a deadly poison. He must punish them for their sin (9:7‑9).

Yahweh will bring terrible destruction upon Jerusalem. The city and its environs will be desolate. When the question is asked: Why has this been done, the answer will be that Yahweh has punished His people (9:10‑16).

A dramatic presentation is given of professional women being called to mourn Jerusalem’s destruction (9:17‑22).

A final challenge is made to the “wise men.” True wisdom is to understand and to know Yahweh who exercises ḥesed, justice, and righteousness. These are the things in which He delights. Furthermore, in the future God is going to judge both Israel (circumcised) and the Gentiles (uncircumcised). Indeed Israel is uncircumcised of heart (9:23‑26).

7. Yahweh speaks of the futility of idolatry (10:1‑16).

Israel is warned not to learn the way of the nations. They should not fear the astrological religion of the pagans. The idols are only wood and stone. It is utter foolishness to fear them (10:1‑5).

Jeremiah extols Yahweh as the one who is great and to whom reverence is due. The wisest of men are stupid when compared to God. Their foolishness is magnified in their following after lifeless idols. Yahweh is the true God and sovereignly in charge of the nations (10:6‑10)

Verse 11 is very strange for it is in Aramaic. Most critical scholars assume it to be a gloss. Thompson says: “It is not impossible that it was a well‑known saying. That it is in Aramaic is no necessary argument for a late date, since Aramaic was widely known in Western Asia and among people on Israel’s borders. Even so, it may represent a marginal note added later by an Aramaic speaker. The thought is in any case not inconsistent with Jeremiah’s outlook.”17 The verse is in LXX and Qumran fragments. The Qumran Hebrew seems to follow the LXX.

Jeremiah returns to the greatness of God. Notice the alternating patterns between God the Unique One and idols (idols: 1‑5; God: 6‑7; idols: 8‑9; God: 10; Aramaic on false gods: 11; God: 12‑13; idols: 14‑15; God: 16). Note that verse 11 as a promise of the demise of idols fits into the last two “God” sections.18

8. Jeremiah gives a graphic message of captivity (10:17‑25).

It is difficult to know how to relate this section to the rest of the chapter. Unless Jeremiah is speaking prophetically, or giving a dramatic presentation of what will happen in the future, there is captivity going on at this time. Perhaps it should be related to 597 BC when Jehoiachin was carried away captive.

Jerusalem is under siege, and Jeremiah tells them to pack their bags for they are leaving. However, it is no accident that they are going, for it is God Himself who is “slinging” them out (10:17‑18).

Jeremiah then identifies with the people and weeps over their calamity. Jeremiah never rejoiced in the judgment on his people. He blames the problem on the shepherds (leaders) who are stupid and have not sought the Lord. Judgment is therefore coming (10:19‑22).

Jeremiah gives a subdued testimony in the last unit of the chapter. He acknowledges man’s sinfulness; he recognizes the necessity of God’s chastening hand; but he asks for God to use moderation and to judge those nations that have devoured Judah (10:2325).

9. Jeremiah delivers the covenant sermon (11:1‑17).

This sermon stresses the covenant Yahweh made with the Israelites at Horeb when He brought them out of Egypt. He swore to them at that time to give them a land flowing with milk and honey. A number of covenants were given to Israel (Abrahamic, Mosaic, Palestinian, and Davidic), but the one stressed here is the one given in Exodus 20 and following. Jeremiah responds by saying Amen, Yahweh! (11:1‑5).

Jeremiah is admonished to preach the covenant sermon all around Judah. The people are to learn that Yahweh judged the people of Israel for disobeying His covenant. The same fate awaits those who disobey Him now (11:6‑8).

Judah is viewed as having entered a conspiracy against Yahweh. They have violated the covenant He gave to their ancestors, and they have sinned in idolatry as their ancestors did. When they are in trouble, God tells them to cry out to their idols for help, but that they will not help them. They have as many idols as they have cities. Because of their violation of the covenant, they are going to be judged. There is no point in Jeremiah praying for the judgment to be lifted (11:9‑14).

The next two verses are difficult. They are in poetic form and therefore were probably delivered at a different time from the rest of the sermon. The mention of idols in v. 13 leads to a condemnation of the Jews who are going to the temple for worship while they follow idols. Yahweh called them a green olive tree, but he is going to set their worthless branches on fire (11:15‑16).

10. Jeremiah’s life is threatened and he complains to Yahweh (11:17—12:6).

Yahweh revealed to Jeremiah that some people were seeking his life. Jeremiah laments his vulnerability and naiveté toward those who planned to kill him. He appeals to the righteous God to judge his case and avenge him of his enemies (11:17‑20).

Yahweh reveals to Jeremiah that it is the men of his own village Anathoth who are plotting against him. He promises to punish them because of their opposition to Jeremiah (11:21‑23).

The poem at the beginning of chapter twelve is placed here because it is the personal complaint of Jeremiah as to why the wicked prosper. He says that God has planted the wicked and caused them to prosper. This is true in spite of their hypocrisy. Jeremiah points out that Yahweh knows him and his attitude toward God. Therefore, Yahweh should judge his enemies since because of their sin, the land is in trouble (12:1‑4).

Yahweh’s response is to chide Jeremiah for his impatience. If you have run with the footmen (false prophets?) and become weary, how can you run with the horses (Babylonian war?). “The land of peace is contrasted with the “swelling of Jordan.” The swelling of Jordan (ge’on hayarden, גְּאוֹן הַיַּרְדֵּן) is the area on each side of the river where the water over floods and leaves rich soil. This caused the underbrush to grow thickly and became a good place for lions to hide; hence a dreadful place. He goes on to tell Jeremiah that members of his own family are plotting against him and that he is to ignore them if they entice him. Since his own family and villagers are mentioned (11:21; 12:6), these pericopes may come from the same period of time in Jeremiah’s life (12:5‑6).

11. Yahweh laments the damage He has had to inflict on His people (12:7‑17).

Without transition, our attention is turned to Yahweh’s lament for His people. He has forsaken Israel, and she has suffered greatly at the hands of her enemies. Shepherds (v. 10) refers to foreign rulers who have attacked Israel and desolated the land. When this took place is not stated, but it could have been the situation spoken of in 2 Kings 24:1‑2, when bands of marauders were sent by Yahweh against Jehoiakim prior to Nebuchadnezzar coming against the city in 597 BC (12:7‑13).

A prose section is added here to say that those “shepherds” who despoiled God’s people will in turn be despoiled. In universal terms God speaks of restoring Judah from the lands where she will be taken captive and of His restoration of the Gentiles who have captured her. This can only speak of the messianic era which the Gentile peoples will be turned to Yahweh (12:14‑17).

12. Yahweh illustrates by a waistband and a proverb His promised judgment on Judah (13:1‑27).

The first illustration is that of the waistband. Jeremiah was to hide it in Perath (פְּרָתָה). This word is usually identified as the Euphrates river, which would be some six or seven hundred miles away. Jeremiah may have made that trip or he may have gone to a stream called Wadi Farah, or he may have had a vision. I would incline to the second view. The rotting of the waistcloth is interpreted to be God’s destruction of His people. The identification with the River Euphrates or a stream sounding like that river should indicate that God will “rot” them by sending them to Babylon in exile (13:1‑11).

The second illustration is the quotation of a proverb: “Every jug (wineskin, nebel, נֵבֶל) will be filled with wine,” that is, the purpose of jugs is to be filled with wine. When the people answer with derision: “Of course we know this proverb,” Jeremiah is to say: “You will drink the wine and become drunk.” Drunkenness represents Yahweh’s judgment upon the people. Jeremiah thrusts at the ruling family in v. 13 (13:12‑14).

The following section speaks of captivity, and since it even speaks of the captivity of the king and queen mother, it may refer to the deportation of Jehoiachin in 597 BC, although the tenses could be prophetic perfects. The compassion of God is evident in His deep groaning for the people who are made to suffer so. Yet they deserve what has happened because they seem to be utterly unable to stop sinning (Ethiopian/leopard) (13:15‑27).

13. Jeremiah identifies with the people in time of drought and judgment (14:1‑22).

This section (1-9) should not be linked chronologically with the one following for the simple reason that the false prophets are saying there will be no famine, but rather peace (v. 13). A drought has taken place that brought with it famine and devastation. Jeremiah, speaking for the people, confesses his sin and cries out for forgiveness and care on the part of God. Even though He acts helpless, He is indeed in their midst and able to deliver (14:1‑9).

Yahweh tells Jeremiah not to pray for Israel because their sin is so great, He is going to call them to account for it. Jeremiah pleads on their behalf that the false prophets are to be blamed for telling them that there will be only peace and prosperity. Yahweh’s reply is that the prophets will be judged by the very things they say are not coming. However, the people are still responsible for their actions and will be likewise judged for their sin (14:10‑16).

The following section like 13:15ff refers to some kind of military campaign. People are crushed, slain, subject to famine and disease and prophets and priests have been deported. Yahweh gives an interesting command to Jeremiah: he is to speak words to them that they themselves would be saying. They cry out to God asking Him if He has completely rejected Judah. They confess their sin and ask Him to remember His covenant. They conclude with a word of confident hope (neqaweh, נְקַוֶּה) in Him (14:17‑22).

14. Jeremiah speaks words of judgment and personal complaint (15:1‑21).

Yahweh tells Jeremiah that even though Moses and Samuel, the two great intercessors, were to pray for the people, He would still send them away. Their judgment will consist of four things: death, sword, famine, and captivity. There will be four dooms: sword, dogs, birds, and beasts. All this is because of the sin of Manasseh the son of Hezekiah who led Judah into such sin (15:1‑4).

Yahweh speaks in poignant terms of Judah’s judgment that will lead them to the point where no one will have pity. The anguish will be unbelievable (15:5‑9).

Jeremiah laments his birth because he has become a man of contention and strife (madon, riv, רִיב). These are court terms again and may mean that Jeremiah is always indicting the people. Yahweh’s answer is not very clear. He seems to be promising Jeremiah protection from the enemy when he comes. This is precisely what happened (Jer. 39:11‑14) (15:10‑11).

The futility of Judah’s resistance against the coming attack is represented in the question: “Can anyone smash iron from the north?” God’s judgment will be irresistible (15:12‑14).

Jeremiah laments again to Yahweh and asks that vengeance be wrought on his enemies. His statement about eating the word of God shows the joy of his ministry in spite of suffering. Furthermore, he does not take any pleasure in the suffering of his people even though they have badly treated him (15:15‑18).

Yahweh gives a very encouraging word to Jeremiah. He must be willing to return (does this imply that Jeremiah had stepped aside for a while?). God promises to make him His spokesman who will deliver messages but receive none. Yahweh will protect him. He will receive stiff opposition, but they will not prevail over him (15:19‑21).

15. Jeremiah, by his life, will communicate a message of judgment to the people (16:1‑21).

Jeremiah is not to get married. The reason he is to give when asked is that those with children and family will suffer dreadfully when the judgment comes (16:1‑4).

Jeremiah is not to enter a house of mourning. The reason is that God is going to bring the judgment of death upon many people and there will be no one to mourn them (16:5‑7).

Jeremiah is not to go to a festive party. The reason is that God is going to eliminate festivity from the people of Judah (16:8‑9).

The people will protest innocently: What have we done? Jeremiah is to answer that their ancestors have sinned and so have they. Therefore, He is going to hurl them out of the land (16:10‑13).

In spite of this negative promise, Yahweh declares that He will return the people of God to their land. As if to smash premature hope, He says He will send for fishermen and hunters to catch them all in their sin for judgment. Finally there is another universalistic statement about the fact that God is going to receive the nations who will forsake their idolatry when they see the greatness of God (16:14‑21).

16. This chapter is a series of miscellaneous messages delivered probably over a period of time (17:1‑27).

Judah’s sin is so indelibly impressed upon their hearts that it is as though it were written with an iron stylus. Consequently, God will judge her (17:1‑4).

A wisdom poem is given on the analogy of Psalm one contrasting the man who trusts in humanity to the man whose trust is in Yahweh (17:5‑8).

A beautiful Psalm is presented showing Jeremiah’s trust in Yahweh and praying for God to protect him from the enemies around about (17:9‑18).

The chapter is concluded in an uncharacteristic way, for Jeremiah admonishes them to observe the Sabbath properly. Heretofore, he has denounced them in scathing terms for their ritualism without reality. However, he is probably using the Sabbath here as part for the whole: because they are abusing the Sabbath and not honoring God on it, they are not honoring God at all.19

B. Potter and Pot—from opportunity to repent to inevitable judgment in captivity (18:1—23:40).

Chapters 18-20 form a triad around the issue of the “pots.” Chapter 18 shows God’s sovereignty in dealing with His people—but they can still repent; Chapter 19 shows through the breaking of the pot the necessity of judgment; Chapter 20 describes the persecution of Jeremiah because of his prophecies of judgment. Chapters 21-23 argue that the responsibility for judgment rests primarily on the leadership.

1. Yahweh uses the potter to illustrate His own dealings with the Jewish people and to show that they had an opportunity to repent (18:1‑23).

Yahweh tells Jeremiah to go to the potter’s house. He probably has a crowd following him to whom he makes his point. The potter is making a vessel of some kind on his wheels. When a defect shows up in the work he crushes it and begins again (18:1‑4).

Yahweh says that the potter illustrates His sovereignty. If He has promised calamity against a nation or good for a nation, He is able to change His mind on the basis of their changed attitude. The application is that Israel should recognize that Yahweh is “fashioning” calamity against them. They therefore should repent. “To fashion” is yatsar (יָצַר). “Potter” is yotser (יוֹצֵר). The same word is used in Genesis 2:7 to describe the creative process. All of this play on words as well as the illustration itself is to warn Judah to repent. However, they say: It is no use! (18:5‑12).

Yahweh then indicts Judah for the foolishness of turning away from Him. He says that one could search far and wide to see if anyone has ever done anything like this and the search would be futile. They have moved from the ancient paths where truth is known. Therefore, God will judge them (18:13‑17).

The response of the people to Jeremiah’s message is plainly seen in v. 18. The general consensus is that “the law will not be lost to the priest, counsel to the sage, nor the word to the prophet.” Jeremiah is just a troublemaker. Consequently, they want to bring him down (18:18).

Because of this terrible response, we hear of one of Jeremiah’s most vitriolic statements against his opponents. He calls upon God to wreak vengeance upon his enemies. This is not what we normally hear from Jeremiah as he identifies with his people. He is probably responding very emotionally to the constant refusal of the people to respond to his message and their insistence that all is well and God cannot judge them because they are fulfilling the ritual (18:19‑23).

2. The message of judgment on Judah (the broken pot—the opportunity is past) (19:1‑15).

God tells Jeremiah to give an illustrated message of promised judgment to the people of Judah. In chapter 18 (probably early in Jehoiakim’s rule) there was still the possibility of repentance. In chapter 19, the opportunity has passed—judgment remains. The components of the illustration are a potter’s earthenware jar (baqbuq yotser harash, 20 There are three valleys around Jerusalem: east is the Kidron valley; central is the Tyropoean (cheese makers) valley; west is the Hinnom valley. All three converge south of the city of David. The Hebrew word for valley is gai. And so the name of the west valley is sometimes called Gai Hinnom (the valley of Hinnom) or Gai bene Hinnom (the valley of the sons of Hinnom). From that comes the corrupted name in Greek of Gehenna. The valley of Hinnom was infamous as a place where people (including King Ahaz) forced their children into a fire to offer them to the god Moloch (2 Kings 16:3, 23:10; Jer. 19:4‑5). It thus becomes a symbol of evil and of burning. By NT times it had become a symbol of eternal punishment and so Jesus used it (Matt. 5:22).

3. The warning of impending doom is given. The calamity will be so great it will make people’s ears tingle (19:3).

The reason given for the coming judgment is their idolatrous practices. They have forsaken Yahweh, made the temple “an alien place,” worshipped other gods, filled this place with the blood of the innocent, built high places to Baal and burned their children in the fire to Baal (19:4‑5).

The judgment is pronounced through a series of word plays. The name of the valley will be changed from Topheth or ben-Hinnom to the valley of Slaughter. Topheth is difficult. It may mean place of burning. Next Yahweh says he will make void the counsel of Judah and Jerusalem; that is, He will frustrate their plans. The word for the jar Jeremiah carries is baqbuq. It is an onomatopoeic word: the name is like the sound. In this case it is the sound of emptying out a bottle. As Jeremiah holds the jar (baqbuq) he says, “I will void (baqothi, בַּקּתִי) the counsel of Judah and Jerusalem.” There will be a horrible slaughter, and in the siege parents will eat their children. This is what happened in 2 Kings 6 (19:6‑9).

Jeremiah then carries out the object lesson by breaking the earthenware jar. The breaking symbolizes the fact that God is going to break Judah. The houses will be defiled like Topheth. Josiah had defiled Topheth to prevent any more child sacrifice there. Precisely what this means is not clear. Did he make it a city dump, so that there was always trash burning there and no one would want to use it for sacrifice. In any event, the city of Jerusalem will be like Topheth when God finishes with it (19:10‑13).

Jeremiah then returns to the city, stands in the court of the temple and extends the same message to the people in general (19:14‑15).

4. Jeremiah is persecuted because of his message (20:1‑18).

At the end of Jeremiah’s message, he is arrested by Pashhur ben Immer who was chief officer (paqid nagid, mahpeketh (מַהְפֶּכֶת) which refers to turning. It probably means that Jeremiah was tortured (20:1‑2).

Jeremiah confronts him the next day when he is released and says that Pashhur’s name is being changed to Magor‑missabib (מָגוֹר מִסָּבִיב). This word means “fear on all sides” and seems to be a relatively common expression in Jeremiah (6:25; 19:3,4,10; 46:5; 49:29; Lam. 2:22). Pashhur will suffer the fate of the city. He will go into captivity and die. We now have serious confrontation over the issue of true versus false prophecy (20:3‑6).

The rest of the chapter gives us a glimpse of the private response of Jeremiah to his persecution. The public response was bold and unequivocal; the private response is bitter. He begins by saying that God has deceived him in leading him into the ministry of prophecy. His bitterness because of the daily derision led him to the point of refusing to speak in the name of the Lord any more. However, the word was so strong in him that he was unable to refrain (20:7‑9).21

Jeremiah has heard of the efforts to defeat him. He seems to imply that his own name is Magor‑missabib. Yet he concludes that Yahweh is with him like a mighty champion (‘arits gibbor, עָרִיץ גִּבּוֹר the first word usually refers to a tyrant and the second to a soldier. These are powerful words to use of God’s ability to deliver). He concludes by singing to the Lord of His deliverance (20:10‑13).

A bitter lament follows on the order of Job’s poem (Job 3) decrying the day of his birth. Keil argues that it is psychologically possible for a person to go from verse 13 to verse 14,22 but it is more probable that Jeremiah composed this section at another time and appended it here as an illustration of his struggle with God when he was persecuted (20:14‑18).

5. Zedekiah sends Pashhur to ask for Yahweh’s help in the Babylonian siege (21:1‑10).

With this unit we turn to the last king of the Judean monarchy. Zedekiah was placed on the throne in 597 BC after his nephew, Jehoiachin, had been taken to Babylon. Zedekiah was twenty‑one years old and ruled until 586 BC. In 588 BC he rebelled against Babylon, and Nebuchadnezzar put the city under siege (2 Kings 24:18—25:3). It is in this latter period that chapter 21 takes place.

The king sent messengers to Jeremiah to seek a word from Yahweh. The Pashhur mentioned here is not the same as the one in chapter 20 (this man shows up again in chapter 38), but the common name is used in the argument. The first Pashhur rejected God’s word of judgment, the second Pashhur comes for help in the midst of the fulfillment of that very word. They ask Jeremiah to inquire of Yahweh (darash, “to seek God’s mind”) in behalf of Jerusalem. Their hope is that God will act miraculously (niphlaoth, as in Judges 6:13 when Gideon asks the Angel of Yahweh where the miracles are of which his fathers spoke) in behalf of the city to deliver her from Babylon. The time for repentance was some ten years prior, but that Pashhur rejected the opportunity. Now only judgment remains (21:1‑2).

Jeremiah reports God’s just response to the request of the king. He will help Judah’s enemies. He will fight against Jerusalem. The “outstretched hand and mighty arm” are a victory motif used by God usually in His defense of His people. He finally promises to deliver the king and the people into the hand of Nebuchadnezzar (21:3‑7).

Yahweh then gives the people a choice. They can choose to surrender to Babylon and live, or they can fight and die. God has set His face against the city for harm (21:8‑10).

6. Yahweh indicts the leaders of Judah to show one of the major reasons for the catastrophe (21:11—23:40).

We now move into a section of the book where the events and messages are not at all chronological. They jump back and forth between Jehoiakim and Zedekiah, and include references to Jehoahaz and Jehoiachin as well. These messages lead to the conclusion that the captivity is unavoidable, and that bad leadership has brought them to this point. Judah has reached the point where she must receive the punishment for her sin.

This series of messages is a compilation of several sermons delivered by Jeremiah against the leadership of Judah with a promise of future leadership that will do God’s bidding. The diversity of these messages is indicated by the prose/poetry constructions as well as the chronological indicators that show them to have been delivered over a period of time.

Jeremiah gives Yahweh’s word against the royal house. This section is in poetry and so was probably given at another time, but it is in this unit because it concerns the same topic. The royal house is admonished to be just in its dealings with the people so as to avoid God’s wrath. The valley dweller/rocky plains refers to Jerusalem (21:11‑14).

These chapters (21-23) contain a scathing denunciation of all the kings after Josiah (except Zedekiah). Jehoiakim comes in for the most sarcastic statement of any Jeremiah makes. After dealing with the sinfulness of these kings, a promise is made of God’s coming Messiah who will rule properly. Finally the section closes with a diatribe against false prophets who are also leaders of the people. These messages were no doubt delivered while each pertinent king was alive. They consist of both prose and poetry and have been brought together here because of the similarity of subject matter.

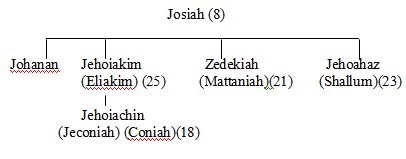

The genealogy according to 1 Chron. 3:14‑15 looks like this:

Johanan is not known outside Chronicles. He must have died young or have been insignificant. Jehoahaz (Shallum) was younger than Jehoiakim, but for some reason was chosen over his older brother to be king. He is listed as the fourth son in Chronicles because he has the same mother as Zedekiah. He had to be older than Zedekiah to have been able to reign in 609 BC

The first unit is not addressed to any particular king. It may have been early in Jehoiakim’s reign before his actions demonstrated an ungodly attitude. In any event the philosophy of kingship is to show justice to all people and particularly to vulnerable ones. God promises that there will be kings on the throne if they obey, but that the temple will be destroyed if they do not. Chapters 24-29 show the results of the failure of the Judean kings to obey—captivity came (22:1‑5).

The second unit is likewise not directed to a king by name, but the tone is hostile. In spite of the position held by David’s descendant in God’s plan, He will bring them down and judge them for forsaking the covenant and worshipping idols (22:6‑9).

The third unit gets specific. It was probably written in 609 BC just after Jehoahaz had been removed from the throne and taken to Egypt. The “dead” in this context is Josiah, the one who “goes away” is Jehoahaz. Then a doleful prediction is made that Shallum will never return to his home. Shallum (שַׁלֻּם) has to do with repayment. A name like Shelemiah would mean “Yahweh repays” (in a good sense). Shallum is the natural name for Jehoahaz as we know from Chronicles, and that may be the only reason it is given here. On the other hand, Jeremiah may be referring to the irony of the name “He got what he deserved” (22:10‑12).

The longest unit is a poetic statement written in vitriolic tones against Jehoiakim. He had apparently set out to build a new palace with cedar walls in spite of the poverty of the people created by raising taxes to pay the tribute demanded by Egypt. His father is held up to him as an example he should follow (v. 15), and he is told that he will die an ignominious death (22:13‑23).

The final unit is delivered against Jehoiachin the young son of Jehoiakim who ruled only three months—long enough to surrender the city to Nebuchadnezzar. The first section is prose and is written prior to his deportation. Here God likens him to a seal ring (a very important item) that He will cast off in spite of its importance. He and the queen mother will be hurled to another country where they will die. The second section is in poetry and takes place after the deportation. Jehoiachin (Coniah) is a despised, shattered jar. God writes him childless, not that he would have no children (we know he had children), but that none of his immediate descendants would sit on the throne (22:28‑30).

The shepherds of Israel are denounced in the beginning of chapter 23. The imagery of sheep and shepherds is common enough in the OT and is of course followed in the NT as well, with Christ being the Good Shepherd. The shepherds are castigated for not doing their job well and are promised judgment. At the same time there is a promise that God will gather His flock and bring them back to pasture (their land) and will raise up over them good shepherds (23:1‑4).

This promise of a future return from captivity and a leadership of good shepherds is the occasion for the next poetic unit to be placed here. The promise is given of a coming “Branch” (tsemah, מְשִׁיחָא). All the ideal actions of a king set forth in this major unit will be carried out by the Branch. As such he will be called “Yahweh, our righteousness” (Yahweh tsidkenu, יהוה צִדְקֵנוּ) which is surely a play on the name of Zedekiah (Yahweh is righteous). A parallel passage is in 33:16 (23:5‑6).

Because of that future glorious work of restoration, the Exodus will pale into insignificance. They will no longer make the creedal statement: “Yahweh who brought us from Egypt,” but they will say “Yahweh who brought us from the land of the north” (23:7‑8).

Jeremiah, mingling his own feelings with those of Yahweh, speaks of the desolation that has come over the land because of the pollution of both prophets and priests. As a result they are promised judgment (23:9‑12).

Yahweh compares the prophets of Judah to those of Samaria. The implication is obvious: the false prophets of Baal misled the northern kingdom and they went into captivity. The same thing will happen to Judah. Their wickedness has become so awful that God must judge them (23:13‑15).

The message of the false prophets can be discerned from the condemnation of their words of peace and prosperity. These prophets do not know the counsel of God. God has sent out His whirlwind and it will not turn back. Furthermore God is near, not far off. No one can hide from Him (23:16‑24).

Yahweh denounces the prophets for their dreams, which He likens to straw (as opposed to grain). God therefore sets Himself against the prophets (23:25‑32).

He tells Jeremiah (singular pronoun) that the only response he is to give when he is asked “what is the oracle of the Lord” is “There is no oracle (What oracle),” Instead the word from God is “I shall abandon you.” The prophets along with the people will be cast out (23:33-40).

This unit began with the house of David, went on to denounce Jehoahaz, Jehoiakim, and Jehoiachin, and finally attacked the religious leaders, particularly the prophets. In the midst of this negative statement is the beautiful prophecy of the Messiah.

C. A series of messages to show the necessity of submitting to Babylonian overlordship (24:1—29:32).

1. Jeremiah delivers a message under the imagery of good and bad figs shortly after the deportation of Jeconiah in 597 BC (24:1‑10).

The vision Jeremiah sees is two baskets of figs sitting before the temple. One basket contains very good figs and the other rotten figs (24:1‑3).

The basket of good figs represents the captives. Those who have gone to Babylon, says Jeremiah, are better off than those who remain, because God is going to bring them back to the land and establish a wonderful spiritual relationship with them (notice the rubric “they will be My people and I will be their God”) (24:4‑7).

The basket of bad figs represents those who will remain in the city as well as those who have fled to Egypt (to escape the Babylonian captivity). They will be given up to the sword, famine, and pestilence. The purpose of the “fig” messages is to say that captivity is God’s sovereign purpose for His people. The fact that that purpose is being carried out is good, even though the effects in the short run are painful. This chapter should be tied in with 23:39-40 (24:8‑10).

Small wonder Jeremiah’s message was despised. The captivity in Babylon was looked upon as a horrible thing and prophets even predicted a return within two years. Jeremiah, on the other hand, tells them it is better to be in Babylon than Jerusalem and predicts the desolation of Jerusalem.

2. Jeremiah predicts seventy years of captivity. The time is the fourth year of Jehoiakim and the first year of Nebuchadnezzar (25:1‑38).

The chronology of this chapter is very important. Pharaoh Necho had put Jehoiakim on the throne in 609 BC Now Nebuchadnezzar has forced Jehoiakim to capitulate to his rule. This takes place in the first year of Nebuchadnezzar (605 BC) and in the fourth year of Jehoiakim. Daniel lists this as the third year of Jehoiakim (25:1-2).23

The message of Jeremiah is that he has spent twenty three years prophesying to them; that God has sent prophets continually to prophesy to them, but they have not listened to anything God told them to do. Chapter 25 seems to have been placed here to reinforce the message of Chapter 24, namely, the disaster that came upon Judah was engineered by God in response to a rebellious people (25:3‑7).

The result of this disobedience through idolatry is that God will bring Nebuchadnezzar (note the phrase “My servant” in v. 9) to attack the city and carry the people away for seventy years (25:8‑11).

Yahweh then promises deliverance after the seventy years are expired. The Babylonians will be appropriately punished24 for their abuse of God’s people (25:12‑14).25

Through the commonly used imagery of drinking a wine cup of wrath, Jeremiah tells the surrounding nations that God is going to judge them as well as Judah: Egypt, foreign people, Uz, Philistines, Edom, Moab, Ammon, Tyre, Sidon, coast lands, Dedan, Tema, Buz, Arabia, foreign people (desert), Zimri, Elam, Media, north, earth. Last of all Sheshach will drink the cup. This latter name is called an athbash or a reversal of the alphabet (a=t [a=z], b=sh [b=y]. Hence, Sh=b, sh=b, k=l or Babel (שֵׁשַׁךְ=בַּבַּל). One wonders whether ambassadors from other nations might have been at Jerusalem to whom Jeremiah offered the drink. If they refuse, he is to tell them that they will drink regardless of whether they accept the cup (25:15‑29).

The wrath of God against the nations is depicted as God roaring from on high and carrying out a court case against the nations. There will be great judgment against the nations. Finally, Yahweh, under the imagery of a lion, attacks the shepherds of the flocks (kings and rulers) and brings devastation to them (25:30‑38).

3. Jeremiah delivers another “temple” sermon and almost loses his life (26:1‑24).

This message takes place in the beginning of Jehoiakim’s reign. That is prior to his submission to Babylon. Bright says that this is a technical expression for the time before his first regnal year, i.e., between Sept. 609 and April 608.26

The reason for the positioning of this unit is not obvious.27 It may be that, like Chapter 25, the point of the placement is to show that from 609 on there was a bitter rejection of Jeremiah’s message. Therefore, the calamity of 586 was inevitable, given the hardened attitude of the king and people to a message requiring repentance. The sermon is an abbreviated version of the one given in chapter 7. Failure to obey God will result in the temple becoming like Shiloh and the city becoming a curse (that is “may you become like Jerusalem” or some such) (26:2‑9).

The priests, prophets and people demanded Jeremiah’s death because of his prophecy against the city, but the princes intervened by sitting in judgment on the case. Jeremiah defended his ministry to the princes, called for repentance, and placed himself in the hands of the princes with the warning that they must give an account to God (26:10‑15).

For unknown reasons, the officials sided with Jeremiah against the priests and the prophets. They cited Hezekiah’s willingness to listen to Micah when he prophesied against Jerusalem (26:16‑19).

The next unit is treated by some as a continuation of the official’s argument, but it is more likely another example of Jehoiakim’s arrogance against the prophets of God and has been included here to reinforce the picture. Uriah prophesied in the same manner as Jeremiah and was killed, while Jeremiah was protected and survived. Such are the ways of God! (26:20‑24).

4. Jeremiah preaches submission to Babylon under the symbolism of a yoke (27:1—28:17).

It would appear that early in the reign of Zedekiah international intrigue was carried out against Babylon. Various ambassadors were in Jerusalem consulting with Zedekiah when this message was delivered. The symbolism consisted of yokes and ropes around Jeremiah’s neck (27:1‑2).

The message to be delivered to the nations (Edom, Moab, Ammon, Tyre, and Sidon) gives us a pretty good awareness of Jeremiah’s theology that God is working through Babylon. They were to recognize first God’s sovereignty (v. 5), and secondly, His right to give control of the world to whom He chooses (v. 6). Nebuchadnezzar was Yahweh’s servant. Those nations who refused to submit to the yoke of Babylon would be judged by the Lord. They were not to listen to their religious leaders because they would cause them to go into captivity (27:3‑11).

Jeremiah made a personal plea to young king Zedekiah, to the priests and to all the people. He tells them that the vessels left by Nebuchadnezzar in his first foray would eventually go to Babylon. They would stay there until Yahweh in His grace brought them back to Jerusalem (27:12‑22).

We now come to a major confrontation between a true prophet and a false one. Hananiah called himself a prophet and came from the town of Gibeon. He addressed a crowd of people in the temple and told them that within two years the temple vessels, Jeconiah and all the exiles would come back to Jerusalem. God would have broken the yoke (symbolically worn by Jeremiah) of the King of Babylon (28:1‑4).

Jeremiah seemed to be somewhat puzzled in his response. He said “amen” to Hananiah’s prophecy but reminded him that the test of prophecy is fulfillment. Hananiah then broke the wooden yoke Jeremiah was wearing and reiterated his prophecy of the defeat of Nebuchadnezzar within two full years (28:5‑11).

Yahweh sent Jeremiah back with the message that the yoke of wood would become a yoke of iron since He had assuredly given Nebuchadnezzar charge of the human arena. Then in a dramatic statement Jeremiah told Hananiah that he was a false prophet. To demonstrate the veracity of the true prophet, Jeremiah predicted Hananiah’s death two months later (cf. 28:1). Hananiah died on the seventh month of that year (28:12‑17).

5. Jeremiah reinforces his message of judgment from God through Babylon by telling the captives to settle down for a long stay (29:1‑32).

Jeremiah sends a letter in a diplomatic pouch to the exiled leaders (elders, priests, prophets, and people) who were in Babylon. Zedekiah had sent official letters to Babylon by Elasah ben Shaphan (29:1‑3).28

The contents of the letter in fine are that they are to settle down, build houses, enter into marriage contracts, and pray for the peace of the city. They are not to let the prophets in exile deceive them when they tell them not to unpack (29:4‑8).29

The letter goes on to give good news. The exile will be long, but only seventy years. After that God’s good plans for them is to bring them back and to restore a relationship between Him and His people (29:9‑14).

This chapter is a collage of material derived from more than one letter and from responses to the letters. There may have been several pieces of correspondence between Jeremiah and the exiles. Verses 1-23 are the first letter to which Shemaiah responds in 24-32. A second letter quoting Shemaiah and telling how his letter was handled follows (29:15‑32).30

Prophets in Babylon. These prophets are again apparently prophesying an early return of the captives, because Jeremiah says that those remaining behind will suffer more than those who went into captivity (29:15‑20).

Ahab ben Kolaiah and Zedekiah ben Maaseiah. These two men are prophets who are prophesying falsely. They will be delivered to the king of Babylon and be roasted in fire (Kolaiah, קוֹלָיָה sounds like roasted grain, qali, , and roasted [in fire], qala, qelalah, קְלָלָה). Their sin is two‑fold: they have prophesied falsely and committed adultery. D. J. Wiseman discusses a rebellion against Nebuchadnezzar about 595 BC and says “It has also been suggested that the rebellion involved some of the Judean deportees in Babylonia since Nebuchadrezzar also put to death by burning Ahab ben Kolaiyah and a Zedekiah ben-Maaseyah who had prophesied that the Jewish exile would last only two years in contrast to the seventy predicted by Jeremiah” (29:21‑ 23).31

Shemaiah the Nehelamite. Nehelamite means “the dreamer” and may have reference to claims to revelation through dreams (cf. 23:25). Shemaiah’s letter to Zephaniah is in response to the letter of the first part of this chapter. He urges Zephaniah to lock Jeremiah up since his words are discouraging. Zephaniah read the letter to Jeremiah (did they have a laugh together?), and Jeremiah sent a word to all the exiles denying Shemaiah’s prophecies and predicting that he will have no descendants (29:24‑32).

D. Jeremiah gives several messages of hope for the future of Israel (The Book of Comfort) (30:1—33:26).

Verses 1‑3 seem to be a heading to the unit of hope. Jeremiah’s messages have contained dismal predictions, at best (including the seventy years of captivity in chapter 29). Now Judah’s attention is turned to the future. She indeed must suffer because of her sin, but the covenant keeping Yahweh will not forget His own. The messianic allusions earlier in the book are augmented by some of the most beautiful prophecy in the Old Testament (30:1‑3).

Before Israel can enjoy God’s ultimate blessing, she must endure suffering. This “time of Jacob’s trouble” is to be equated with the tribulation period from which God promises to save Israel. When that salvation takes place, the yoke will be broken off and they shall serve the Lord their God and David their king. This refers to the Millennium. Will David rule as king during the Millennium (cf. Ezek. 37:25)? I believe the reference to David here is to the Messiah of whom David is the type (30:4‑9).

A message reminiscent of Isaiah’s servant songs is next appended (it is poetry). This is a promise of restoration after chastening. The chastening is necessary because “her wound is incurable” (30:9‑17).

A beautiful poem on the restoration of Israel follows describing the rebuilding of the city. In addition their leader will be “one of them” who will be able to approach God. They will “be my people and I will be their God” (30:18‑24).

The message of hope continues with a depiction of God’s everlasting love. He uses the words of Jeremiah’s call in describing the rebuilding and replanting of Israel. “Arise, and let us go up to Zion, to the Lord our God” (31:1‑6).

The references to Israel probably indicate messages directed to the North early in Jeremiah’s ministry when Josiah was extending his rule to the North.32 Specific statements are made about the return of Israel form the north. What a marvelous and miraculous event this will be. This is no modern “Zionist” movement where a limited number of Jews return to Israel. This is a worldwide restoration of Jewish people in preparation for the Millennium (31:7‑9).

Yahweh summons the nations and coast lands to witness His miraculous work in restoring Israel to happiness and satisfaction (31:10‑14).

This idyllic scene is interrupted with a reminder of the suffering through which Israel must go before she can be restored. Rachel weeps for her children who languish in the exile (Matthew uses this picture to describe Israel’s anguish over the slaughter of the infants by Herod). God agonizes over the pain of His people (31:15‑20).

A series of messages are joined together promising the return of Israel. “A woman will encompass a man” is most difficult. It seems to be a proverb of sorts and is to represent something most unusual (“a new thing the Lord has created in the earth”). It may mean that Israel (a woman) is to turn and embrace the Lord (the man), that is, she will repent.33 Another brief statement is given about the restoration of Judah (31:21‑26).

The only place a new covenant is mentioned in the OT is in this context (but the conditions are promised in Ezek. 36:22-32). God promises restoration again, but he speaks of the fact that He will make a new covenant with Israel that will involve internal conversion. This covenant will be different from the Mosaic covenant. They will know Yahweh so well, that they will not even have to teach one another. Their sins will be forgiven. This passage underlies Hebrews 8 where it is cited fully. The work of Christ at Calvary is the basis for the new covenant including the church and the new covenant that will restore Israel’s fortunes (31:27‑34).

The assurance of God’s faithfulness to Israel is His comparison with the astral heavens. If this fixed order should depart, then He could cast off Israel, but since it cannot, than He can never cast off His people (31:25‑38).

By citing specific physical characteristics of the city of Jerusalem, Yahweh promises the restoration and protection of Israel.34

The siege is coming to a conclusion. Things look hopeless; and from a human point of view they are. Jeremiah, because of his “seditious views” is locked up. He has predicted that Jerusalem will be taken, Zedekiah carried off to Babylon, and the futility of resisting Babylon (32:1‑5)

The Lord tells Jeremiah to prepare for an unusual request from his uncle with reference to a field. The purpose of this divinely planned incident, is to give hope to the people. This situation is the matter of goel (גּאֵֹל) redemption of land sold due to poverty as set out in Lev. 25:25. Hanamel asks him to buy his property in the hometown village of Anathoth. This is a notoriously poor investment. The land is surrounded by Babylonians; everyone is about to lose their property; nothing is worth anything, and yet Hanamel wants Jeremiah to buy his land. Since Jeremiah knows now that it is from the Lord, he proceeds to carry out the transaction. He takes witnesses, writes a deed, pays seventeen shekels of silver and tells Baruch to put the deed where it will endure for a long time. The key words are “houses and fields and vineyards shall again be bought in this land” (32:6‑15).