7. 2 Kings

Related MediaSecond Kings1

Since 1 and 2 Kings are really one book, the outline will continue.2

[The names of northern kings are italicized in these notes, when outside of a heading.]

H. Elijah opposed Ahaziah (2 Kings 1:1‑18).

1. Moab threw off the Israelite yoke (1:1).3

2. Ahaziah was injured and inquired of a pagan god (1:2‑4).

a. He sent messengers to inquire of Baal-Zebub (Zebul) of Ekron.4 There is intended irony that a king of Israel inquired of a pagan god, “will I recover from this sickness?” In 8:8 a pagan king inquired of Yahweh with the very same words (1:2).5

b. Elijah intercepted the messengers at Yahweh’s direction and challenged Ahaziah. Elijah told the messengers that Ahaziah would die (1:3‑4).

3. Ahaziah ascertained that the man was Elijah and sent army men to capture him (1:5‑14).

a. The prophet Elijah was distinctive in appearance: he was hairy and wore a leather belt. This sounds much like John the Baptist (1:7‑8).

b. Ahaziah sent a squad of fifty soldiers, but they were killed by fire. He sent a second squad, and they were killed. He sent a third squad, and the officer pled with Elijah (1:9‑14).6

4. At God’s encouragement, Elijah went down to Ahaziah and repeated the message about his death (1:15‑18).

The purpose of this unit is to show that Yahweh is the God of Israel. Kings should submit to him and not go to foreign gods for their messages.

IV. Elisha and Jehu against Baal—2 Kings 2:1—10:36 (841‑814 B.C.).

A. The mantle of the prophetic leadership passes from Elijah to Elisha (2:1‑25.)

We have already discussed the relationship between Elijah’s flight to Sinai and Moses’ activity in the wilderness. We should also see similarities in this account and that of Moses and Joshua as well. Hobbs says: “Within the stories of Elisha (chaps. 2‑8; 13) there are also a number of items of style that warrant brief notice. As with the kings, one model dominates the traditions concerning Elijah and Elisha. That model is Moses. This is nowhere more evident than in the transition from the ministry of Elijah to Elisha in chaps. 1‑2. The narrative is so constructed as to present a smooth transition from one to the other, but the narrative is also dominated by allusions to incidents from the career of Moses, and indeed Joshua. This is especially clear in the location of the ascension of Elijah and the actions which accompany that ascension.”7

1. Elijah and Elisha went to Bethel (2:1‑4).

The “schools of prophets” (bene hannevi’im בְּנֵי הַנְּבִיאִים) had their beginning apparently under Samuel’s ministry. The precise nature and composition of the bands is not clear, but they did apparently live in groups; there was much poverty (vow of poverty?); they had “heads” (Samuel, Elijah, Elisha) and special disciples (Elisha to Elijah and Gehazi to Elisha); they carried prophetic statements to the kings (often negative in content). In this chapter there are groups in Bethel and Jericho (at least fifty in Jericho and one hundred at Gilgal in 4:38-44) as well as at Naioth in Ramah (1 Samuel 19).8 Both Gilgal and Bethel have ancient spiritual connotations. Because of the role they played in the invasion under Joshua, so does Jericho. As a matter of fact, the incident of dividing of the waters (Red Sea: Moses, Jordan: Joshua), this incident is being tied into the pristine past.

2. Elijah and Elisha went to Jericho (2:5‑6).

There was a community awareness that Elijah was going to be removed from the prophets. They kept telling Elisha about it, but he essentially ignored them.

3. Elijah was transported to heaven and Elisha received a double portion of his spirit (2:7‑14).

While the Jericho band was watching, Elijah divided the Jordan, and he and Elisha crossed it. Elisha asked for a double portion of the spirit, and Elijah said he would have it if he saw his departure. Elijah was translated before over fifty watching people, and Elisha tore his garments into two (double portion), took Elijah’s mantle, smote the Jordan River and it parted. The allusion to the double portion for the first‑born (Deut. 21:17) is not accidental. Truly Elisha had succeeded Elijah.

4. The prophets accepted Elisha’s leadership (2:15‑18).

Apparently, it was customary for Elijah to disappear under the influence of the Spirit (Obadiah was afraid this would happen in 1 Kings 18). The prophets sent fifty men to search for him, but they did not find him as Elisha had predicted.

5. Elisha purified the water at Jericho (2:19‑22).

The following series of miraculous acts by Elisha are not to be considered mere anecdotes of his life and ministry. These are confirmatory acts. The “sons of the prophets” saw the transfer of authority, but they now see the concomitant ability attached to it.9

The Hebrew word “unfruitful” in v. 19 (mešaccalet מְשַׁכָּלֶת) is otherwise used of miscarriage. It may be that the families were having difficulty carrying pregnancies to term. Salt had a very important place in the ancient medicinal process. This fountain is identified with the spring near modern Jericho, ‘Ain es-Sultan, or Elisha’s spring.

6. Elisha called judgment on the young people who mocked him (2:23‑25).

This miraculous act is quite troubling on the surface. It seems more the petulant act of an irritated man than a godly response of a prophet of Yahweh. Two issues have led some to argue that there is more than meets the eye: the bald head is said not to be typical for those who live outdoors a lot in the middle east.10 Therefore, some would argue that it represented some kind of priestly tonsure. The second issue is the locale of the event. Bethel was where some of the prophets were located as we are told in 2:3 (Jeroboam’s cult was centered here as well). Consequently, some would argue, these children (they are little youths, [ne’arim qetannym נְעַרִים קְתַנִּים]) were offspring of some of the prophets who were rejecting the authority of the prophetic office of Elisha. However, this kind of speculative reconstruction needs to be viewed with caution. The least that can be said is that God does not take lightly the mocking of his holiness (as with touching the ark and burning up the fifties that came against Elijah).

B. Elisha guided Jehoram and Jehoshaphat in their war against Moab (3:1‑27).

1. Jehoram succeeded Ahab and was as wicked (3:1‑3).

Jehoram was the second son of Ahab who ruled after his brother Ahaziah from 852 to 841 B.C. He also was wicked, but the statement against him is ameliorated by the fact that he removed the Baal pillar his father had made. These pillars (maṣebboth מַצֵבּוֹת) were objects of veneration.11 Therefore, some would argue that it represented some kind of priestly tonsure. The second issue is the

2. Jehoshaphat allied with Jehoram as he had with Jehoram’s father, Ahab. He seemed determined to maintain this non-spiritual relation-ship (3:4‑8).

a. There were friendly relations between the Davidic dynasty and the Omride family in the north. This culminated in the marriage alliance of Ahab and Jezebel’s daughter, Athaliah, to Jehoshaphat’s son. This proved to be a disaster, for Athaliah inherited all her mother’s devious skill.

b. There are two accounts of the rebellion of Moab against Israel. One is the biblical reference of chapter 3 that speaks of a punitive expedition against Moab by Israel and Judah, joined by Edom.12 This ended in a bloody defeat for Moab, but the long-term results were indecisive. Moab was not returned to “the fold.” The other account comes from the King of Moab himself.13

“I am Mesha, son of Chemosh [. . . ], king of Moab, the Dibonite—my father had reigned over Moab thirty years, and I reigned after my father,—(who) made this high place for Chemosh in Qarhoh [. . . ] because he saved me from all the kings and caused me to triumph over all my adversaries. As for Omri, (5) king of Israel, he humbled Moab many years (lit., days), for Chemosh was angry at his land. And his son followed him and he also said, “I will humble Moab.’ In my time he spoke (thus), but I have triumphed over him and over his house, while Israel hath perished forever! (Now) Omri had occupied the land of Medeba, and [Israel] had dwelt there in his time and half the time of his son [Ahab], forty years; but Chemosh dwelt there in my time.”14 Either the subjugation began when Omri was still an officer or 40 represents a round number (testing?) since total rule of all Omri is 44-48 years. “Son” must mean grandson. (Nine lines out of twenty-two). The Moabite stone was discovered in 1878.

3. When they were in distress, Jehoshaphat called for a true prophet as he had done before, and Elisha appeared (3:9‑12).

The logistics of moving a large number of troops through the wilderness of Edom are considerable, and they ran out of water. Elisha was near enough for them to make personal contact with him.

4. Elisha rebuked Jehoram as Elijah had rebuked Ahab, but then promised help for the sake of Jehoshaphat (3:13‑20).

Elisha scathingly denounced Jehoram and demanded to know why he did not consult his own deity. Jehoram rather humbly replied that it looked as though these three kings had come together for defeat. Elisha promised provision and victory for the sake of Jehoshaphat.

On the harp playing and prophecy, Hobbs says: “This incident is unique in the stories of the prophets and provides one of the very few glimpses at the mechanics of prophetic inspiration. To generalize from this lone incident to a theory of prophetic inspiration, even for this early period of prophecy, would be unwise.15 Music and musicians play a role in the activity of the band of prophets descending from the high place in 1 Sam 10:1-16, but other means of inspiration such as vision and audition are also found in the OT (Jer 1:11-15, etc.). That this was typical, or that one can appeal to the analogy of the dervish guilds of a much later age for parallels (so W. R. Smith, The Prophets of Israel, 2nd. Ed. [London: A. C. Black, 1895] 391-92, are unwarranted conclusions. Cf. also J. Lindblom, Prophecy in Ancient Israel, 59.”16

5. The Moabites were defeated, and the king committed a horrible act in sacrificing his eldest son (3:21‑27).

“Anger against Israel” is a problem. The word translated “anger” (qeṣep קֶצֶף) means just that in Hebrew, but in Syriac, it means to be “sad” or “anxious.” The word “against” can also mean “upon” or “on.” Perhaps the Israelites became so upset over this horrible deed that they withdrew. “There was great sadness on Israel.” Surely, we cannot assume that God’s anger was against them for the deed of the Moabite king. Margolit agrees. He cites Ugaritic for the practice of offering the first born.17

C. Elisha performed several local miracles (4:1‑44).

1. Elisha provided for the financial needs of one of the prophet’s widows (4:1‑7).

This is a touching story of God’s provision for the needs of his servants. This woman does not seem to be living with a group, which might argue against the idea that the prophets lived communally. It probably does reflect a general situation of virtual poverty among the prophets. With so much venal prophecy going on, the only way they could protect their spiritual integrity was not to take money for their ministry.

2. Elisha prophesied that the Shunammite woman would become pregnant (4:8‑17).

The story of the gracious lady of Shunem has caught the fancy of people for generations. She was generous with this man who probably lived on just such provisions. (Our phrase “prophet’s chamber” comes from this story.) She had no material needs, but she desperately wanted a child which he promised her.

3. Elisha raised the Shunammite woman’s dead son (4:18‑37).

Doubly bitter is the sorrow of a woman who had been given a child after years of hopelessness only to have it taken in death. Small wonder that she spoke so bitterly to Elisha about frustrated hope.

Gehazi was unable to raise the boy as Jesus’ disciples had been unable to cast out the demon. When Jesus raised the only son of a widow lady (Luke 7), people concluded that a great prophet had arisen in their midst.

4. Elisha purified the poison stew (4:38‑41).

Elisha’s ministry was confirmed also in the miracle of the stew. There was a famine in the land, and the prophets were eating whatever they could get their hands on. As a result, there was poisoned food. Elisha purified it.

5. Elisha fed a hundred men with twenty loaves (4:42‑44).

Like Jesus feeding the five thousand, Elisha multiplied the meager food to feed an impossible number of people. No wonder the people said of Jesus, “He is Elijah, Jeremiah or one of the prophets” (Matt 16:14).

D. Elisha performed a miracle of international dimensions (5:1‑27).

1. Naaman came to the king of Israel for healing (5:1‑7).

We have already seen the continuous warfare between the Syrians and the Israelites. In this story, a Syrian army general came to the king of Israel and demanded healing. This was an important man who had come with credentials from the Syrian king. Small wonder the king of Israel was in great consternation and could only assume that Syria was looking for a chance to start another war.

The purpose of this section is the same as 2 Kings 1, that the Syrians might know that there is a God in Israel (cf. 2 Kings 5:8).

2. Elisha sent for Naaman and told him to wash in the Jordan (5:8‑14).

Elisha’s intent was to let this foreign general know that there was a prophet (of Yahweh) in Israel. As a foreigner, worshipping foreign gods, Elisha wanted him to come to know the reality of Yahweh God of Israel. This indeed happened. Elisha, acting the part of a prophet above king or general, disdained even to greet Naaman. The latter almost lost his opportunity to be healed because of his pride. He did as he was told and came back healed.

3. Naaman acknowledged Yahweh as God and wanted to pay Elisha (5:15‑19).

This is a marvelous account of a man in Old Testament times who became intellectually convinced of the truth of the existence of one God named Yahweh. It is almost amusing to see Naaman struggle with the issue of compromise as a subordinate officer. He prays for Elisha’s forgiveness if he has to go to the temple of the Syrian gods with his master. Elisha concedes the situation.

4. Gehazi’s greed led him to lie to become rich (5:20‑27).

The historian is not only revealing God’s word to us, he is also a masterful storyteller. The account of the naive Gehazi, struggling with greed in the midst of poverty yet surrounded by Naaman’s wealth is as true to life as it is pathetic. His lust led him to lie to the one man who would always know whether he were lying and from that to the leprosy of Naaman. Elisha, like Paul, knew that an effective ministry to a corrupt society depended on being free from the taint of purchased ministry. There was no place in Elisha’s work for a man who would sell his ministry for money.

E. Elisha performed another miracle with the prophet band (6:1‑7).

Elisha caused an iron axe head to float. Intriguing questions are raised by this pericope: what kind of a building were they constructing? Did they live as in a commune? Does the borrowed axe represent poverty? The story is given to add to the weight of confirmation of Elisha’s ministry. This miracle shows God’s control over nature.

F. Elisha performed miracles against the Aramean king (6:8‑23).

1. He warned the king of Israel of the Arameans’ location (6:8‑14).

2. The Aramean king sent a small army to capture Elisha (6:15‑19).

3. (If an Aramean king could move with impunity into Israelite territory to try to capture Elisha, what must this say about the impotence of the king of Israel?)

4. Elisha led them blinded to the king of Israel who released them at Elisha’s orders (6:20‑23).

This miracle shows God’s control over Syria.

G. Elisha spoke for God in delivering the city of Samaria from the Arameans (6:24—7:20).

1. The siege caused tragic circumstances (6:24‑31).

Food had become so scarce that mothers were eating their babies. The king was asked to judge between two women who were quarreling over the fact that one mother would not produce the baby she had promised for food. The king blamed Elisha for the problem and threatened to kill him.

2. Elisha responded to the king’s threat with a scathing remark and a promise of deliverance (6:32—7:2).

The king had sent a messenger, and he came later. Elisha knew they were coming and told the elders with whom he was sitting. The king told him that there was no point in waiting on Yahweh anymore. Elisha promised that food would be in abundance on the next day. A royal advisor mocked the promise, and Elisha predicted his death.

3. God gave a great victory without any human help, and four lepers discovered the abandoned camp (7:3‑8).

The account of four discards from society discovering the abandoned Syrian camp is a delightful and ironic story. The powerful army of the Syrians, such a dire threat to Israel, was routed by a sound the Lord caused them to hear.

4. The lepers brought the news to the gate (7:9‑15).

The lepers collected items until they were sated and became uneasy for not telling those in the city. The people are skeptical at first, but the king reconnoitered and discovered that it was true.

5. Elisha’s prophecy proved to be true in all the details (7:16‑20).

This miracle is more typical of the prophetic actions than most of the others in the Elisha section. God had apparently brought judgment on Samaria in the form of the siege. The King was religiously wearing sackcloth but was unrepentant in heart. The desperate circumstances of the siege finally drove him to challenge Elisha and Yahweh. God vindicated himself and his prophet by bringing great deliverance apart from human ability. The disdainful advisor was killed as Elisha had predicted (you will see it, but you will not eat it).

H. Elisha warned the Shunammite woman of a coming famine, and she fled. When she returned, the king was told of Elisha’s miracle with her (8:1‑6).

Since Gehazi is presented here with the king, it is probable that this event took place before chapter 5 (Gehazi was a leper after that). This story is told to show the ability of Elisha to prophesy and to indicate the influence he had even on the king.

I. Elisha anointed Hazael to be king over Syria (8:7‑15).

1. Elijah had received, as part of his recommissioning, the respon-sibility of appointing three people whom God would use in the battle against Baal: Elisha, Jehu and Hazael. God’s involvement through his prophets in Syria is almost the same as his work among the people of Israel. During this time there seems to have been a fair amount of contact between the prophets and Syria. The time has now come to anoint Hazael to be king over Syria (1 Kings 19:15‑18). That assignment was carried out by his disciple.

2. Elisha told Hazael, Ben-Hadad’s messenger, that the king would recover from his sickness (this sickness was probably a battle wound), but in an aside, he told Hazael the king would die. The man was perplexed until Elisha told him that he would be the next king. Presumably, Ben-Hadad began to get well the next day, but Hazael killed him and became king in his place. Shalmaneser III says of these two kings: “I defeated Hadadezer of Damascus together with twelve princes, his allies. I stretched upon the ground 20,900 of his strong warriors like su-bi, the remnants of his troops I pushed into the Orontes river and they dispersed to save their lives; Hadadezer (himself) perished [N. B. he does not say how he perished]. Hazael, a commoner (lit.: son of nobody), seized the throne, called up a numerous army and rose against me. I fought with him and defeated him, taking the chariots of his camp. He disappeared to save his life. I marched as far as Damascus, his royal residence [and cut down his] gardens.”18

J. Jehoram began to reign in Judah (8:16‑24).

Jehoram was allied by marriage with the house of Ahab (8:16‑24).

1. The bad blood of the Ahab/Jezebel family was transferred to Judah when their daughter, Athaliah, married Jehoshaphat’s son, Jehoram. She later became queen of Judah. The impact of this alliance on Jehoram was devastating. The south was as ripe for judgment as the north, but God postponed judgment because of the Davidic covenant (8:16‑19).

2. The only act of Jehoram recorded in Kings is his attack on Edom. Edom revolted, and though Jehoram won a battle against them, he was unable to restore them to vassal status. Libnah is otherwise unknown but was probably a border Judean town. This rebellion shows the general state of chaos beginning to develop in Judah and is given here to show the beginning of God’s judgment on Judah for her sins (8:20‑24).

K. Ahaziah began to reign in Judah (8:25‑29).

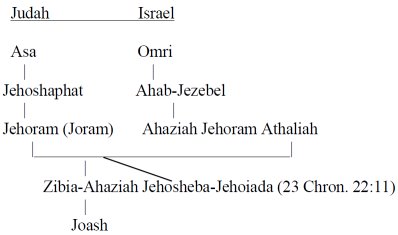

There are so many similar names in this section, we will need a chart to keep them sorted out.

1. NASB’s “granddaughter” in v. 26 is a correct translation, but it is really “daughter” in Hebrew. “Son” and “daughter” can be used of any descendant or even of a successor (as in Daniel). The translation “son-in-law” of the house of Ahab is not a good translation. This Hebrew word ḥathan חֲתַן) means to be related by marriage. In this context, it is referring to the fact that the Davidide dynasty has become intermarried with the Omride dynasty (8:25‑26).

2. Ahaziah acted like the house of Ahab (as was to be expected under the circumstances) and, like his father, became entangled with an alliance with Israel to fight the Arameans at Ramoth-gilead. Jehoram of Israel was wounded in the battle. When he was recuperating in Jezreel, Ahaziah, his nephew, came to visit him (8:27‑29).

L. Elisha and Jehu began to exterminate Baal worship in Israel (9:1‑36).

1. Elisha sent a prophet to anoint Jehu, an officer in Jehoram’s army (9:1‑13).

Jehu was an older, experienced officer, having fought with Ahab. Elisha sent one of the prophets to anoint Jehu over Israel to avenge the blood of Naboth and the prophets of Yahweh whom Jezebel had slain. He interrupted the meeting, anointed Jehu, and fled. Jehu’s fellow officers then proclaimed him king, and he began his extermi-nation of the dynasty of Ahab.

2. Jehu killed Jehoram and Ahaziah (9:14‑29).

Jehu rode furiously to Jezreel, the royal house, where he killed both Jehoram and his nephew Ahaziah. There is an apparent discrepancy in the accounts of Kings and Chronicles on the place and manner of Ahaziah’s death. Chronicles is a very abbreviated account because it is not concerned with the northern dynasty. Keil shows how some of it can be harmonized but says that the details are too sparse to allow for complete understanding. We will have to leave it at that.

3. Jehu killed Jezebel (9:30‑37).

This is the account of the clash of two proud, callous people. Jezebel showed her character by painting herself to look nice in death and defying Jehu to kill her. She called him Zimri, because Zimri killed Elah and in turn only lived seven days. Jehu showed his character by sitting down to a full meal after the grisly death of Jezebel. In fulfillment of Elijah’s prophecy, the dogs ate much of her body and carried most of it off.

4. Jehu had seventy sons of Ahab killed (10:1‑11).

Jehu’s bold ruthlessness intimidated the elders of Samaria into killing seventy of Ahab’s sons and sending their heads to Jehu who told the people that he had nothing to do with their deaths.

5. Jehu killed forty-two relatives of Ahaziah (10:12‑14).

Jehu in a very bloody manner killed these relatives of Ahaziah who were coming up to visit him.

6. Jehu allied with Jonadab the Rechabite (10:15‑17).

Jonadab was a member of the semi-nomadic Rechabites who had little sympathy with the soft living of the royal house. He linked hands with Jehu to further the purge of Ahab’s house. (For Jeremiah’s use of the descendants of Jonadab three hundred years later as examples of obedience, see Jeremiah 35.)

7. Jehu killed Baal adherents in Baal’s temple (10:18‑28).

Through an ingenious subterfuge, Jehu trapped a large number of adherents in the temple of Baal and killed them. They destroyed the sacred pillars and the temple of Baal. This action of Jehu was a major blow at the official cult of Baal. Two kings, the original promoter of Baalism (Jezebel), and many adherents were dead. The temple was destroyed, and the new king was an ardent advocate of Yahweh. Therefore, the historian can say that Baal had been eradicated. Baalism continued to be a significant force in Israel, but officially it was struck a mighty blow.

The prophet Hosea was ministering during the reign of Jeroboam II, a great‑grandson of Jehu. The times are corrupt as is the house of Jeroboam. Hosea predicts judgment on that dynasty and says: “for yet a little while, and I will punish the house of Jehu for the bloodshed of Jezreel, and I will put an end to the kingdom of the house of Israel” (Hosea 1:4). Something about Jehu’s acts did not please the Lord. Was it his attitude?

8. Jehu continued to pursue religious policies of the Jeroboam cult (10:29‑31).

Three major reform movements began and failed in Israel. Jehu’s reform was fairly superficial and short-lived, partly because Jehu’s spirituality was questionable. Hezekiah’s reform and Josiah’s were more significant in the south and also came from men who were far more committed to Yahweh. Yet they failed. Hezekiah still faced an Assyrian invasion and Josiah was killed at Megiddo, and his movement ceased. In all this the inevitability of judgment because of the sins of the people seems to be in the foreground of the historian’s mind. These efforts at reform, as important and valuable as they were, were insufficient to turn around this rebellious and sinful people. (There were other reform movements of less significance such as Asa’s and Jehoshaphat’s).

9. God began to cut off Israel piece by piece (10:32‑36).

God’s judgment, culminating in the Assyrian deportation of 722 B.C., began here. This encroachment on Israel’s property by others is an indication of God’s displeasure with Israel.

V. The divided kingdom to the fall of Samaria (841‑722 B.C.)—2 Kings 11:1—17:41.

A. God protected the Davidic line through Joash (11:1‑21).

1. Athaliah took the throne and tried to kill all the royal seed (11:1‑3).

Ahaziah was killed by Jehu and Athaliah, his mother, took the throne. She murdered the royal seed, but her daughter (or stepdaughter), Jehosheba, rescued Joash and kept him alive (her husband was Jehoiada the priest). Joash was protected for six years in the temple while Athaliah ruled.

2. Jehoiada organized a coup d’état (11:4‑16).

Jehoiada carefully organized the troops, brought out the king and crowned him. Athaliah was murdered, and the Ahab/Jezebel family finally came to an end.

3. Jehoiada made a covenant between the Lord and the king and the people to return to him (11:17‑21).

B. Joash (Jehoash) began to rule in Judah (12:1‑21).

1. Joash followed Yahweh under the tutelage of Jehoiada (12:1‑3).

2. Joash set about to repair the temple which had been damaged by Athaliah and her sons (2 Chron 24:7) (12:4‑5).

3. The Priests apparently used the money for their own maintenance and had none left over for the repair (12:6‑7).

4. The king took the project out of their hands and collected the money separately (12:8‑16).

5. Hazael, king of Syria, captured Gath and besieged Jerusalem. Joash bought him off (12:17‑18).

6. Joash’s later years were characterized by apostasy. He re‑instituted Baalism and even killed Jehoiada’s son Zechariah for speaking out against him (2 Chron 24:15‑24).

7. Joash was assassinated by his servants (12:19‑21).

C. Jehoahaz and Joash ruled in Samaria (13:1‑25).

1. Jehoahaz ruled seventeen years (13:1‑9).

He was an evil king, and God delivered him over to Hazael. At Jehoahaz’s entreaty, Yahweh gave Israel some relief from Hazael. Israel did not turn away from their sins, however, and Yahweh allowed them to be reduced to a virtually non‑existent army. Jehoahaz died.

2. Joash ruled sixteen years (13:10‑13).

Joash like his father was a wicked king. He fought against Amaziah, king of Judah. Joash died.

3. A vignette about Elisha is given at the conclusion of the Joash chronicle that took place before Joash had died. Elisha was about to die, and Joash came down to weep for him. Elisha showed him through shooting an arrow that he would have victory over Aram. Elisha showed him by having him hit the arrows on the floor that he would have three victories (but only three since he only hit three times) (13:14-19).

4. Elisha’s body was the cause of a dead man being revived. Joash had the three promised victories over Aram (13:20-25).

D. Amaziah ruled twenty-nine years in Judah (14:1‑22).

1. He was generally a good king (14:1‑4).

He is faulted, as are so many kings, for not removing the high places. Again, this reflects the later judgment on the high places when they were totally compromised with Baalism.

2. He killed those who had assassinated his father (14:5‑6).

Amaziah’s desire to keep the law of Moses was evidenced in the refusal to kill the children of the Assassins.

3. He had a great victory over Edom (14:7).

God gave him a great victory, but it caused him to become proud and led him to an ill-advised war with Israel. The Chronicler adds a unit on his apostasy (2 Chron 25:14-16).

4. He then picked a fight with Israel (14:8‑14).

Joash (king of Israel) warned him against the provocation, but he refused to pay attention. Israel won the battle. (A parable is given in which the thorn bush tries to form a marriage alliance with the cedar. This may indicate that a real attempt had been made by Amaziah to forge a marriage alliance with Joash. Amaziah was taken hostage and Azariah served as co-regent.)

5. A side note is given on Joash (14:15‑16).

Information on the reign of the northern king is given here because he was mentioned in this context.

6. Amaziah was assassinated in Lachish (14:17‑22).

The people became dissatisfied with King Amaziah for some reason, and he was forced to flee to Lachish, but they pursued him there and killed him. Then his son Azariah (Uzziah) became king at age sixteen. Azariah (Uzziah) rebuilt the port city of Elath.

E. Jeroboam II ruled forty-one years in Samaria (14:23‑29).

1. He was an evil king (14:23‑24).

Jeroboam was the last significant king in the Jehu dynasty (his son ruled six months). During his rule the northern kingdom regained some of its former glory. Hosea and Amos both prophesied during his reign and excoriated king and people for an opulent life style that resulted in further departure from Yahweh and oppression of the poor.

2. He restored the borders of Israel (14:25‑27).

a. The borders were pushed to Hamath in the north and to the Dead Sea in the south as prophesied by Jonah (14:25‑26).

Cohen says, “Assyria lay nearly prostrate before its northern foe; it was impoverished and dispirited. Well might a prophet be believed who would proclaim: ‘Yet forty days, and Nineveh shall be overthrown!’”19

b. The historian gives God’s reasons for preserving Israel in spite of their wickedness (14:27).

3. He restored territory that had once belonged to Judah under David. It was as far north as Hamath (but not including it) and Damascus (included); hence he had conquered the kingdom of Damascus (14:28).

4. He died and Zechariah, his son ruled in his place (14:29).

F. Azariah (Uzziah) ruled fifty-two years in Judah (15:1‑7).

1. Azariah was essentially a good king (15:1‑4).

It is good when a king rules well and long. He is charged in the matter of the high places, but otherwise he followed the Lord.

2. He was punished for entering the priestly office (15:5).

The office of the priest was historically carefully separated from that of the king. David was involved to some extent in a priestly function (e.g., when he brought up the ark), but that was the exception. The intrusion into the priests’ office was dealt with by God to show that it was improper (cf. 2 Chron 26:19).20

3. He was a very successful king (2 Chronicles 26).

2 Chron 26:6 speaks of the expansion of the kingdom under him.

4. He died and Jotham took his place (15:6‑7).

G. Five kings ruled in Samaria, reflecting a time of insecurity (15:8‑31).

1. Zechariah son of Jeroboam ruled six months (15:8‑12).

He was a wicked king who only lasted a short time. He was assassinated by his successor, bringing an end to the dynasty of Jehu in the fourth generation as God had promised (15:12).

2. Shallum, Zechariah’s murderer, ruled one month (15:13-16).

The anarchy continued when Menahem murdered Shallum after the latter had ruled for only one month. (This was not a good time to be king!) Menahem took over.

3. Menahem, Shallum’s murderer, ruled ten years (15:17‑22).

He was an evil king. He bribed Pul (Tiglath-Pileser) to confirm and support his reign. Assyria now began to meddle in the west more and more. Tiglath-Pileser says: “[As for Menahem I ov]erwhelmed him [like a snowstorm] and he . . . fled like a bird, alone, [and bowed to my feet(?)]. I returned him to his place [and imposed tribute upon him, to wit:] gold, silver, linen garments with multicolored trimmings . . . great . . . [I re]ceived from him. Israel (lit.: “Omri‑Land” Bit Humria) . . . all its inhabitants (and) their possession I led to Assyria.”21 Menahem died.

4. Pekahiah, Menahem’s son, ruled two years (15:23‑26).

He was an evil king, and he was assassinated by his successor, Pekah.

5. Pekah, Pekahiah’s murderer, ruled twenty years (15:27‑31).

The long stable rule of Uzziah in the south is in stark contrast to the chaos of the time during which five different kings ruled in the north. Pekah assassinated Pekahiah. He was an evil king. Assyria captured cities from him and carried away captives. He was assassinated. Tiglath-Pileser says: “They overthrew their king Pekah and I placed Hoshea as king over them. I received from them 10 talents of gold, 1,000(?) talents of silver as their [tri]bute and brought them to Assyria”22

H. Jotham, Uzziah’s son, ruled sixteen years in Judah (15:32‑38).

1. He was a good king (15:32‑35).

A series of good kings ruled in the south. Jotham is pronounced a good man except for the perennial matter of the high places.

2. Pekah and Rezin of Syria came against him (15:36‑37).

This diabolical combination will still be in existence in the days of Ahaz when they make a devastating attack on Jerusalem and bring forth the great prophecy of Isaiah in chapter 7.

3. Jotham died and was succeeded by his son Ahaz (15:38).

I. Ahaz, Jotham’s son, ruled sixteen years in Judah (16:1‑20).

1. Ahaz was a wicked king (16:1‑4).

He even passed his son through the fire (the consummate sin) and practiced the Canaanite religion (16:4).23

2. Israel and the Arameans conspired against him (16:5‑6).

They attacked Jerusalem. For the prophetic view on this entire incident, see Isaiah 7. There Isaiah met Ahaz and challenged him to trust in Yahweh rather than in human help. He offered Ahaz any sign in heaven or earth to confirm his faith, but he refused. Out of that incident grew the great virgin prophecy.

The Arameans’ strength is indicated when they take the port city of Elath from Ahaz, deport the Jews and resettle it with their own people. When we remember that Elath is at the head of the Gulf of Aqaba, this is a remarkable statement of Judean weakness.

3. Ahaz sent to Tiglath-Pileser (16:7‑9).

In spite of Isaiah’s exhortation, Ahaz bribed Tiglath-Pileser with money from the temple to put pressure on Syria and Israel. Tiglath-Pileser attacked Syria, and they withdrew from Judah (Assyria would have come west to suppress the rebellion of Pekah and Rezin without Ahaz’s encouragement.)

4. Ahaz copied a pagan altar (16:10‑16).

Ahaz’ syncretism is evidenced in that he was enamored of an altar he saw when he went up to visit Tiglath-Pileser. Consequently, he had plans drawn of the altar, copied it and set it up in the temple precincts. His vassalage to Assyria probably involved some religious sub-servience as well.

5. Ahaz removed much of the temple furniture “because of the king of Assyria” (perhaps to keep him from getting them) (16:17‑18).

6. Ahaz died leaving only the marks of his apostasy (16:19‑20).

J. The judgment of God came upon the kingdom of Israel (17:1‑41).

1. Hoshea ruled nine years, but Assyria defeated him and deported Israel because he conspired against Assyria (17:1‑6).

Sargon II says: “At the begi[nning of my royal rule, I . . . the town of the Sama]rians [I besieged, conquered] (2 lines destroyed) [for the god . . . who le]t me achieve (this) my triumph. . . . I led away as prisoners [27,290 inhabitants of it (and) [equipped] from among [them (soldiers to man)] 50 chariots for my royal corps . . . [The town I] re[built] better than (it was) before and [settled] therein people from countries which [I] myself [had con]quered. I placed an officer of mine as governor over them and imposed upon them tribute as (is customary) for Assyrian citizens”24

2. The historian explains why all this happened (17:7‑23).

This extended sermon is given by the historian, writing from the perspective of early in the Judean exile, to explain the deep apostasy into which Israel had fallen. He begins with their deliverance from Egypt and shows that throughout their history they had followed pagan religious practices until they reached the point of no return. Judgment, long promised by the prophets, came.

The historian explains that Judah sinned also following the practices of the north, but their time had not yet come.

3. The mixed population asked for an Israelite priest since they were not doing well in the land (17:24‑33).

A priest was brought back who taught them about Yahweh. In light of the northern history, one has to wonder what this priest taught them. In spite of this teaching about Yahweh, each ethnic group carried on its own religious practice, and chaos ensued. This is the beginning of the “Samaritan” sect.25

4. The historian gives a final word explaining historically the problem of rejecting Yahweh (17:34‑41).

At the time this book was composed, these polytheistic practices were still going on. Ezra and Nehemiah should be read to gain insight into the practices of these syncretistic Jews in the north and those left in the south after the debacle of 586 B.C. The final word of the historian is telling: “So while these nations feared the Lord, they also served their idols; their children likewise and their grandchildren, as their fathers did, so they do to this day” (17:41)

VI. Judah to the captivity (716‑586 B.C.) (2 Kings 18:1—25:30).

A. Hezekiah’s good reign over Judah (2 Kings 18—20).

1. Hezekiah was 25 years old when he became king and he reigned 29 years (18:1‑2).

2. Hezekiah was a good king in spite of the spiritual apostasy of his father (18:3‑8).

He was pleasing to Yahweh. He destroyed much of the idolatry including the bronze serpent Moses had made (neḥash hanneḥosheth נְחַשׁ הַנְּחשֶׁת). The historian says that there was no king prior to Hezekiah who trusted Yahweh as he did (hence, he trusted him more than David) nor was there any like him afterward. 2 Kings 25:24‑25 says almost the same thing about Josiah. The difference between the two men was apparently a matter of emphasis: Hezekiah trusted Yahweh while Josiah was carrying out the directions of the newly discovered law book. Both were outstanding, godly kings. (This statement may be simply a strong way of saying they were very good kings.) Because of his trust in Yahweh, Hezekiah received the blessing of Yahweh. He successfully rebelled against the Assyrian overlord and defeated the Philistines.

3. Hezekiah was the king when Israel was deported (18:9‑12).

Shalmaneser is credited with the deportation, but Sargon claims credit in his annals. 722 is the year for the death of Shalmaneser and the beginning of Sargon’s rule. Therefore, they were probably both involved in the act. This section of the synchronization between the northern and southern kingdoms and external dates is fraught with great difficulty.26

The reason for the deportation is stated here succinctly (a longer sermon is given in chap. 17) (18:12).

4. Hezekiah had his troubles with Assyria after he rebelled against them (18:13‑17).

Sennacherib says: “In the continuation of my [third] campaign I besieged Beth‑Dagon, Joppa, Banai‑Barqa, Azuru, cities belonging to Sidqia who did not bow to my feet quickly (enough); I conquered (them) and carried their spoils away. The officials, the patricians and the (common) people of Ekron—who had thrown Padi, their king, into fetters (because he was) loyal to (his) solemn oath (sworn) by the god Ashur, and had handed him over to Hezekiah, the Jew . . . (and) he (Hezekiah) held him in prison, unlawfully, as if he (Padi) be an enemy—had become afraid and had called (for help) upon the kings of Egypt. . . As to Hezekiah, the Jew, he did not submit to my yoke, I laid siege to 46 of his strong cities, walled forts and to the countless small villages in their vicinity, and conquered (them) by means of well stamped (earth‑)ramps, and battering‑rams brought (thus) near (to the walls) (combined with) the attack by foot soldiers, (using) mines, breeches as well as sapper work. I drove out (of them) 200,150 people, young and old, male and female, horses, mules, donkeys, camels, big and small cattle beyond counting, and considered (them) booty. Himself I made a prisoner in Jerusalem, his royal residence, like a bird in a cage. I surrounded him with earthwork in order to molest those who were leaving his city’s gate. His towns which I had plundered, I took away from his country and gave them (over) to Mitinti, king of Ashdod, Padi, king of Ekron, and I still increased the tribute and the katru‑presents (due) to me (as his) overlord which I imposed (later) upon him beyond the former tribute, to be delivered annually. Hezekiah himself, whom the terror-inspiring splendor of my lordship had overwhelmed and whose irregular and elite troops which he had brought into Jerusalem, his royal residence, in order to strengthen (it), had deserted him, did send me, later to Nineveh, my lordly city, together with 30 talents of gold, 800 talents of silver, . . . In order to deliver the tribute and to do obeisance as a slave he sent his (personal) messenger.”27

a. Sennacherib came west to suppress the rebellion begun by Hezekiah (18:13).28

b. Hezekiah capitulated and paid the required tribute (18:14‑16).

5. A suggested sequence for this difficult chronology is as follows: 29

a. Hezekiah rebelled against Assyria (18:7).

b. In the fourteenth year, Sennacherib came west, and Hezekiah promised to submit (18:13‑16).

c. Sennacherib sent messengers to challenge Hezekiah (18:17‑37).

d. Isaiah promised deliverance through a rumor (19:7).

e. Rabshakeh pulled back after hearing of Tirhakah (19:9).

f. He sent more letters to Hezekiah (19:10).

g. Hezekiah prayed and Isaiah promised deliverance (19:14‑34).

h. Sennacherib’s army was struck and 185,000 were killed (19:35).

i. Sennacherib was assassinated by his sons (19:37).

6. Sennacherib decided to punish Hezekiah (18:17‑37).

a. His representatives came to Jerusalem and stood at the very spot Isaiah had met Hezekiah’s father, Ahaz (Isa 7:1-3), and admo-nished him to trust Yahweh rather than go to Assyria for help (18:17).

b. Rabshakeh challenged Hezekiah’s officials as to their ability to withstand the great force of Assyria. He asked them whom they could rely on: Egypt? Yahweh? (saying that Hezekiah had offended him by removing his high places). He asked them whether they could mount horses with soldiers if he gave them the horses (a real insult). Finally, he told them that Yahweh himself had sent Sennacherib to destroy the land (18:18‑25).

c. The Rabshakeh then addressed the people directly. The officials tried to get the Rabshakeh to speak in Aramaic, the trade language of that era, rather than in Hebrew. The Rabshakeh refused and redoubled his efforts to convince the people to surrender and let him deport them to another land. In the process he blasphemed Yahweh by considering him to be as any other god. The people did not respond (18:26‑36).

d. The officials brought this report to Hezekiah with clothes torn as a sign of mourning (18:37).

7. Yahweh responded to Hezekiah’s trust and delivered Judah from Sennacherib (19:1‑37).

a. Hezekiah sent to Isaiah the prophet for spiritual help (19:1‑5).

The godly character of Hezekiah is shown in this time of crisis. He recognized that all his political acumen would not deliver him from this dilemma. Consequently, he went to the prophet Isaiah to ask him for prayer. The contrast between Hezekiah and Ahaz is sharp.

b. Isaiah responded that God would answer his prayer and deliver Judah (19:6‑7).

c. The Rabshakeh lifted the siege because of confusion about the location of Sennacherib (19:8‑9).

d. He sent a threatening letter to Hezekiah (19:10‑13).

e. Hezekiah took the letter to the Lord and prayed for deliverance (19:14‑19).

f. Isaiah brought a message from the Lord stating his sovereignty and promising to judge the Assyrian (19:20‑28).

g. Yahweh even gave a sign to Hezekiah (19:29‑34). (Note the Davidic covenant again in 19:34).

h. Yahweh sent a plague killing 185,000, and Sennacherib returned home and was assassinated by his sons (19:35‑37). (Compare Isaiah 36‑39, a parallel account used by the author of Kings. See f.n. on p. 308).

8. Hezekiah became sick, and his life was prolonged by Yahweh (20:1‑21).

a. Hezekiah became sick and was told by Isaiah that he would die. Hezekiah prayed for healing, and Yahweh answered his prayer and gave him fifteen more years. He gave him a sign (backward movement of the sundial or of the shadow on the stairs—same miracle) (20:1‑11).

b. The newly emerging power, Babylon, sent ambassadors to inquire of Hezekiah’s health (ostensibly) and to promote western resistance to Assyria (20:12‑19).

The Arameans who had infiltrated the southern end of the Meso-potamian valley and insinuated themselves into the government of Babylon were trying to break away from a weakening Assyria. Berodach or Merodach sent messengers west to foment trouble (20:12).

Hezekiah followed the new policy of supporting anyone but Assyria that would prove fatal to the Judean kingdom (20:13).

Isaiah rebuked him for this indiscretion and promised judgment on Judah through Babylonia (20:14‑19).30

c. Hezekiah died. Mention is made of the pool and the conduit he built (20:20‑21).

The inscription found on the wall of Hezekiah’s tunnel reads as follows: “[. . . when] (the tunnel) was driven through. And this was the way in which it was cut through:—While [. . . ] (were) still [. . . ] axe(s), each man toward his fellow, and while there were still three cubits to be cut through, [there was heard] the voice of a man calling to his fellow, for there was an overlap in the rock on the right [and on the left]. And when the tunnel was driven through, the quarrymen hewed (the rock), each man toward his fellow, axe against axe; and the water flowed from the spring toward the reservoir for 1,200 cubits, and the height of the rock above the head(s) of the quarrymen was 100 cubits.”31

B. Manasseh became king at the age of 12 and had a long, wicked rule of fifty-five years (21:1‑18).

1. Manasseh had a very negative impact on Judah (21:1‑9).

He restored the idolatry Hezekiah had destroyed. He built pagan altars in the temple. (Note the astral religion of the Assyrians.) He sacrificed his son in the fire and practiced sorcery and witchcraft. He put a carved image of Asherah in the temple. The historian reminds us of the sacredness of the temple and of Yahweh’s promised blessing for obedience.

2. Yahweh spoke a message of judgment against Manasseh through the prophets (21:10‑15).

He ascribed the reason for the judgment to Manasseh’s perfidy which he said was worse than all the Amorites before him. He promised an “ear tingling” judgment on Judah and Manasseh. Furthermore, Jerusalem and Manasseh would suffer the same kind of judgment brought against Samaria and Ahab.

3. The historian recorded further evil deeds of Manasseh (21:16‑18).

Manasseh was also a cruel murderer. Chronicles records that Man-asseh was carried to Babylon in fetters where he repented and was returned to Jerusalem. However, his repentance was too late, and the results of his evil too entrenched to allay the judgment (2 Chron 33:10‑13.) The later Jews, curious about the content of Manasseh’s prayer, wrote one—”The Prayer of Manasseh.”

C. Amon became king at age 22 and ruled only two years (21:19‑26).

1. Amon was also wicked, walking in all the ways of his father and forsaking the Lord (21:19‑22).

2. Amon was assassinated by his servants and the people of the land made Josiah king (21:23‑26).

D. Josiah became king at age eight and ruled thirty-one good years (22:1—23:30).

1. Josiah came to the throne as a minor, and under the tutelage of someone like Jehoiada, was a spiritual boy and later a spiritual man (22:1‑2).

2. Historical survey of the last days of Judah.

|

640‑608 |

Josiah reigned in Judah. He began reform in his 12th year (628‑7) and extended it further in his 18th year (623‑2) after weakness of Assyria became apparent when they were driven from Babylon by Nabopolassar (626‑5). Hogarth, CAH, III, 146, thinks the Scythians may have broken Assyrian power in the west. Egypt also felt free to begin to move. Jeremiah began his ministry in the 13th year of Josiah (Jer 1:2). |

|

627 |

Jeremiah was called to the prophetic ministry at a young age. |

|

624 |

At age sixteen, Josiah began to seek the Lord. |

|

622 |

At age 18, he began to purge Judah and Jerusalem of idolatry. |

|

626‑623 |

Tablet #25127 (British Museum).32 |

|

|

Nabopolassar defeated the Assyrian army at the gates of Babylon and was crowned king of Babylon—November 23, 626. Nabo-polassar was not strong enough to attack Nineveh. |

|

616‑608 |

Tablet #21901 (British Museum). |

|

|

A gap covering 622‑617 exists. |

|

|

Medes were the head of an anti-Assyrian group. Egypt had allied herself with Assyria. |

|

614 |

The Medes defeated Asshur in 614. Nabopolassar joined them and defeated Nineveh in 612 B.C. The Book of the Law was found in the temple, bringing further reform. The waning power of the Assyrians allowed Josiah to take the reform movement into the northern area that was formerly Israel. These people were still Jewish, however mixed with foreigners. They were basically apostate, and Josiah tried to influence them spiritually. |

|

612 |

A remnant of the Assyrian army fled to Haran under Assuruballit II who tried to reconstitute the kingdom. They were forced out of Haran by Babylon in spite of extensive Egyptian help in 610. The Egyptians joined Assyria in an effort to retake the garrison in 609 but failed. Josiah tried to interdict the Egyptian army at Megiddo and was killed. (2 Kings 23:28-30; 2 Chron 35:20-27. Chronicles referred to the battle area as Carchemish.) The Egyptians at this point take over control of Syria after the defeat of the Assyrians. Pharaoh-Necho on his way back, deposed Jehoahaz who had ruled only three months after the death of Josiah, his father, and puts Jehoiakim, another son of Josiah, on the throne. |

|

607‑696 |

Tablet #22047. |

|

|

Babylonian armies under Nabopolassar and Nebuchadnezzar battle against mountain people and try to control Egyptians in Syria. The latter were entrenched at Carchemish. Nabopolassar returned to Babylon in 606‑5 where he died. |

|

605‑594 |

Tablet #21946. |

|

|

Nebuchadnezzar in sole command of the army, marched against the Egyptians at Carchemish and defeated them. Jer 46:2 places this in the fourth year of Jehoiakim. (cf. also Jer 25:1, who relates the fourth year of Jehoiakim to the first year of Nebuchadnezzar.) |

|

605 |

Nebuchadnezzar came against Jerusalem and Jehoiakim became his vassal. (2 Kings 24:1) (Dan 1:1 says that in Jehoiakim’s third year Nebuchadnezzar carried off captives. Daniel must be using the accession year of Nebuchadnezzar which was not counted as his first year.) Cf. also 2 Chron 36:6 where Jehoiakim is bound but apparently not carried off, or perhaps he was taken to Babylon in a victory parade and then returned to Jerusalem. |

|

601‑600 |

In December Nebuchadnezzar marched against Egypt. Judah was probably still a vassal of Babylon. (He would not likely have left his rear exposed to a hostile army.) The battle was fierce and Babylon suffered heavy losses. Nebuchadnezzar returned to Babylon to regroup his army. (ANET sup. p. 564). It was probably at this time that Jehoiakim rebelled (2 Kings 24:2). |

|

600‑599 |

While Nebuchadnezzar was refurbishing his troops, Judah en-joyed a measure of independence, but Nebuchadnezzar probably was involved in encouraging other of his vassals against Jerusalem (2 Kings 24:2). |

|

598 |

In December Nebuchadnezzar came west again to put an end to the rebellion. Jehoiachin, son of the now dead Jehoiakim, was on the throne. On March 16, 597, Jerusalem was defeated, Jehoia-chin and others were deported to Babylon, and Zedekiah, another son of Josiah, was put on the throne. |

|

595‑4 |

A local rebellion in Babylon led Zedekiah’s advisors to believe they could throw off Babylon’s yoke. This was in direct oppose-tion to the word of the Lord (cf. Jer 28:1ff). |

|

586 |

In spite of Jeremiah’s constant urging to submit to the yoke of Nebuchadnezzar as God’s servant, Zedekiah entered into alli-ances to revolt against Babylonia. Nebuchadnezzar came west and besieged the city of Jerusalem in 588. After one and a half years, the walls were breached. Zedekiah tried to escape but was captured and sent to Babylon. The city was destroyed, the temple was razed, and many people were taken into captivity. The final destruction of the city and temple are absent from the Babylonian Chronicle due to a gap. The data for that final destruction and deportation are found in 2 Kings 25 and 2 Chronicles 36. |

|

|

Gedaliah, a member of the royal family, was appointed governor by the Babylonians. Just three months after the fall of the city, he was assassinated, and the remnant fled to Egypt. Jeremiah and Baruch were also taken to Egypt, where Jeremiah continued to prophesy to an unrepentant people. |

|

582 |

Jer 52:30 speaks of a deportation of 745 people in this year. Was this a punitive raid to deal with the assassination of Gedaliah? |

|

560 |

Thirty-seven years after the first attack on Jerusalem, Jehoiachin was elevated by Evil-Merodach (Ewal-Marduk) 2 Kings 25:27‑30. He seemed to be regarded as the official king even in exile (cf. Ezek 1:2).33 |

3. Josiah began to repair the temple as had Joash (22:3‑7).

4. The priest, Hilkiah, found the book of the law (22‑8‑13).

a. This may be the book of Deuteronomy, or it could be the entire Pentateuch. Probably it is the former since it was read in what appears to be a rather short time. Additionally, it is the Palestinian covenant to which Yahweh seems to refer (22:8‑9).

b. Shaphan reported to Josiah that the repairs had been made and that they had found the law book (22:10).

c. Josiah was dismayed when he read the book because its contents had not been obeyed by the fathers (22:11‑13).34

5. Yahweh, through Huldah, the prophetess, told Josiah that He was going to bring the judgments mentioned in the book of the law upon Judah, but that Josiah would be spared because he had humbled himself (22:14‑20).

6. Josiah and the people entered a covenant to keep the contents of the book (23:1‑3).

7. Josiah then began to purge the temple (23:4‑14).

He removed the vessels dedicated to pagan deities and got rid of the idolatrous priests. He destroyed the idols and the houses of the male prostitutes. He tried to bring the Levitical priests from the various high places to the religious center at Jerusalem, but not all came. He defiled Topheth in the valley of Hinnom to prevent any more dedication of children to the god Molech. He got rid of the horses and chariots dedicated to the sun. He got rid of altars on the roof of the palace and the altars in the two courts and tore down the high places Solomon had erected to various foreign gods.

8. Josiah then began to purge the northern kingdom (23:15‑20).

a. The ability to move into the area ruled by Assyria shows that Assyrian power had weakened considerably. Whether Josiah had political aims in the north as well can only be conjectured.

b. He tore down the altar at Bethel and so fulfilled the prediction of the prophet in 1 Kings 13. He acknowledged the tomb of the prophet who had predicted that Josiah would destroy the altar. He destroyed temples in Samaria and killed the priests who were serving them.

9. Josiah then celebrated the Passover (23:21‑23).

10. Josiah extended the reform (23:24‑25).

He got rid of the mediums and spiritists to conform to the word of God in the law. He received the highest encomium possible in that day.35

11. All Josiah’s good work did not atone for the sins of Judah. Yahweh had determined judgment, and it would be carried out in time (23:26‑27).

12. Josiah was killed trying to support the ill-advised policies instituted by his great-grandfather, Hezekiah, viz., to support the Babylonians against Assyria. Pharaoh Necho was going to the support of a weakened Assyria, and Josiah was killed trying to intercept him (23:28‑30).

E. Josiah’s son Jehoahaz, an evil young man, was put on the throne by the people, but he was deposed by Pharaoh Necho after only three months (23:31‑33).

F. Jehoiakim, another son of Josiah, was put on the throne by Pharaoh Necho as a vassal to Egypt (23:34—24:7).

Jehoiakim was wicked also. Nebuchadnezzar came against Jerusalem in 606/5 and Jehoiakim became a vassal to Babylonia. These judgments, says the historian, were God’s punishment for disobedience. Jehoiakim died after eleven years of rule (age 36). He was probably killed in a palace coup.36

G. Jehoiachin, Josiah’s grandson, ruled only long enough to surrender the city to Nebuchadnezzar the second time (24:8‑17).

There had been a rebellion against Babylonia. The vessels of the temple were deported as well as the choice artisans of the city (Ezekiel was in this group). Jehoiachin was also deported.

H. Zedekiah, a third son of Josiah, became king at the age of twenty-one and ruled eleven years (24:18—25:21)

Scope of the deportation: “Casual readers of the Bible generally assume that virtually the entire population of Judah was carried off to Babylon at this time with only the most derelict remaining behind. This picture may not be accurate. H.M. Barstad, for instance, while agreeing that Nebuchadnezzar did serious damage in the capital and crippled the national leadership, interprets the archaeological and textual evidence as indicating that the basic structure of society stayed substantially intact.”37 For an opposing view, see Yigal Levin, “Ancient Israel Through a Social Scientific Lens,” BAR 40, no. 5 (2014): 43–47, 66. He quotes Faust extensively who argues that the land was empty.

1. Zedekiah was a wicked king who also rebelled against Babylonia (24:18‑20).

2. Nebuchadnezzar besieged the city again (25:1‑7).

The city was under siege for over two years. The Babylonians broke into the city. The king and his family were taken to Riblah to be judged by Nebuchadnezzar. Zedekiah’s sons were slaughtered before his eyes, and he was blinded.

3. Officers returned to Jerusalem to destroy the temple and the houses and to deport more people and more temple treasure (25:8‑17).

4. Key Jewish rulers were executed (25:18‑21).

I. Nebuchadnezzar appointed Gedaliah as governor of the people to be left in the land (25:22‑26).

1. Gedaliah promised the people they would be all right if they would obey the king of Babylon (25:22‑24).

2. Gedaliah was assassinated, and the people fled to Egypt (25:25‑26).38

J. Jehoiachin was elevated in captivity and given a daily allowance (25:27‑30).

We have now come to the end of an era. The kingdom is defeated, there is no king, and the temple as the visible symbol of God’s presence (and blessing) is destroyed. During the exile there must be a reevaluation of the spiritual perspective of the people. There must be an explanation of the events that happened. There must be a regrouping with a new approach to Scripture, synagogue and separation. Chronicles, Ezra, and Nehemiah will contribute much to that practice and theology.

1See my God Rules among Men, for an integrated harmony with Chronicles.

2For an excellent discussion of the literary composition of Second Kings, see T. R. Hobbs, Second Kings, pp. xvii-xxx. He represents a school of thought that refuses to accept the fragmentation caused by form-criticism and seeks to explain divergences and tensions on a literary basis rather than on a form-critical basis. This is a welcome movement, although their work will not be accepted by many. See his commentary for literature on the subject.

3See the discussion at 3:4 for the inscription of the Moabite king who rebelled.

4This name means “Lord of the fly” which is a Jewish pun on “Exalted Lord.”

5See Hobbs, Second Kings, p. xix.

6On this three‑fold repetition see Hobbs: “In chap. 1 the judgment on Ahaziah is found three times, but within this story is another which tells of three attempts to arrest the prophet. In chap. 2, Elisha is reminded three times that his master will leave him and he is also instructed to leave his master. . . . In chap. 4 three attempts are made to raise the dead boy, and in chap. 9 three scouts are sent out to the approaching rebels headed by Jehu. Such threefold repetition is not accidental, but deliberate, and is a common feature of folk literature, offering a rhythm to such stories. Always, on the third ‘beat,’ the story comes to some kind of conclusion” Second Kings, p. xxix.

7Hobbs, Second Kings, p. xxix.

8For an excellent brief discussion on the issue of the sons of the prophets, see Hobbs (Second Kings, pp. 25‑27). He opts for a minimal interpretation of the phenomena of the prophetic movement, I believe too much so, but he is correct in showing that much flesh has been manufactured to cover the bare bones (and many missing at that) in these accounts.

9Note in another context Paul’s statement in 2 Cor 12:12: “The signs of an apostle were wrought by me.”

10Montgomery, Kings loc. cit.

11See pictures of the excavations of Hazor in ANEP for examples.

12The anomaly of Edom joining Judah/Israel is explained by Haran (IEJ 18) by the fact that Edomite king is only a Judean viceroy who joins the battle automatically.

13See S. H. Horn, “Why the Moabite Stone was Blown to Pieces,” BAR, 12:3 (1986): 50‑61 for an excellent popular discussion of this important inscription. See also Hobbs, Second Kings, pp. 39‑40.

14ANET, p. 320.

15Cf. von Rad, Old Testament Theology, 2:59.

16Hobbs, Second Kings, p. 36.

17Margolit, “Why King Mesha of Moab Sacrificed His Oldest Son,” BAR 12 (1986): 62-63.

18ANET, p. 280.

19S. Cohen, “The Political Background of the Words of Amos,” HUCA 36 (1965) 53-160. He goes on to say in f.n. 13, “Although the book is a piece of didactic fiction, it is based on a sound historical reminiscence, for the prophet Jonah ben Amittai (II Kings 14:25) could very well have lived about the time when Nineveh was threatened with capture and destruction.”

20Assyria declined somewhat at the end of the ninth century, but the mighty Tiglath-Pileser III (744‑727) brought his country back to great heights. He campaigned in the west from 743‑738. There he encountered a certain Azariah of Judah in Syria, defeated him and destroyed much of his territory (ANET, p. 282). Some scholars have a problem accepting Azariah as the biblical one, but Bright (History of Israel, p. 252) is surely correct in saying that it would be exceptional to have two kings and two territories with the same name in the same period of time. (See also Tadmor “Azriyau of Yaudi” in Scripta Hierosolymitana 8 [1961] 232-271 for a thoroughgoing defense of the identity.) The devastation spoken of in Isaiah 1 is therefore probably the result of this attack from Assyria, and so, early on Judah came under the shadow of this eastern scourge. Kitchen, OROT, p. 18 says it is unlikely.

21ANET, p. 283.

22ANET, p. 284. For a discussion of the idea that Pekah ruled in Gilead for twelve of his twenty year, overlapping Menahem and Pekahiah, see Thiele, MNHK, p. 63. He cites Hosea 5:5: “Therefore, shall Israel and Ephraim . . . Judah also.”

23See L. E. Stager and S. R. Wolff, “Child Sacrifice at Carthage—Religious rite or Population Control?” BAR 10:1(1984): 31‑51 for an excellent discussion of the Canaanite practice of child sacrifice as carried on at Carthage.

24ANET, p. 284.

25See Macdonald, The Theology of the Samaritans, p. 29. “The later prophets do not refer to the Samaritans, but to Israel, and assume that they are in the plan of God rather than a ‘mongrel’ race. He believes that the Judean account of the origins of the Samaritans is suspect, but this does not mean that the Samaritan account is reliable.”

“Each had polemic reasons to bend history to their own dogmas. Any claim for Samaritan borrowing from Judaism is nonsense, as anyone who has read all the available literary material must judge. What is true beyond doubt is that both Samaritanism and Judaism developed from a common matrix. Both possessed the Law, albeit they were at variance over points of difference in their respective texts of it, and both were evolving in an atmosphere wherein many ideas and ideals were being nurtured.” See also I. Koch, et al. “Forced resettlement and immigration at Tel Hadid,” BAR 46:3, pp. 28-33, for archae-ological evidence of this action by Assyria.

26See Thiele Mysterious Numbers of the Hebrew Kings, and Stigers, “The Inter-phased Chronology of Jotham, Ahaz, Hezekiah and Hoshea,” JETS 9 (1966) 81-90. (Note that the chart on p. 261 shows Hezekiah beginning his rule after the northern captivity took place. Hezekiah must have been co-regent with his father in 722). See also p. 308.

27ANET, pp. 287, 288.

28See ANEP for the siege of Lachish.

29The chronology at the time of Hezekiah is very difficult. In the parallel account of Isaiah, Isaiah takes priority. I owe to Dr. Todd Beall the following argument: 1) Isaiah 36:2 ties in with Isaiah 7:3 (where God tells Isaiah to meet Ahaz). This is important in Isaiah, but not in Kings. 2) “the Holy One of Israel” is used 25 times in Isaiah, elsewhere in the Old Testament only six times. One time in 2 Kings 19:22 (=Isaiah 37:23). So, it would seem to follow that Kings is simply following the Isaiah account, using both the place name in 36:2 that makes sense in Isaiah and the Holy One of Israel name used almost exclusively in Isaiah. 3) The whole mess with the chronology of 2 Kings 18 is solved when one realizes that Kings changes sources in 2 Kings 18:13. But the previous references to Hezekiah’s reign in 2 Kings 18 (vv. 1, 9, and 10) refer to the beginning of his coregency with Ahaz. Why the switch? Well, because in 2 Kings 18:13 the writer of 2 Kings switches to Isaiah’s narrative.

30The structure of the book of Isaiah places chapters 38-39 covering this same situation just before the second section of the book dealing with the Babylonian exile so as to tie together the prophecy of Isaiah with its fulfillment in the exile.

31ANET, p. 321.

32D. J. Wiseman, The Chronicles of Chaldaean Kings (626-556 B.C.).

33For more historical details of this important era, see my notes to the book of Jeremiah in Old Testament Prophets.

34The present prevailing opinion in critical circles is that the history of Israel found in the Bible was written by a school or movement whose theology is reflected in the book of Deuteronomy. These people during and/or after the exile took existing materials and constructed them in such a way as to reflect their interpretation of God’s working in His people. The earlier critical view was that the book of Deuteronomy was concocted out of whole cloth to force upon the people the idea that Yahweh could only be worshipped in the temple at Jerusalem. More recent opinion believes that much of Deuteronomy is old, but that it was put together in the seventh century to bring about religious reform. For a good discussion of this issue, see D. J. Wiseman, “Ancient Orient, ‘Deuteronism,’ and the Old Testament,” pp. 1‑24. See also my comments on p. 176.

35See the comment relative to Hezekiah, loc. cit.

36See Jeremiah 36 for an intimate look at Jeremiah’s relation to this impious king.

Related Topics: Introductions, Arguments, Outlines, Teaching the Bible