6. 1 Kings

Related MediaFirst Kings1

H. Solomon’s Reign (1:1—11:43).

A. The Davidic covenant is implemented in the transition from David to Solomon (1:1‑2:12).

1. David is about to die (1:1‑4).

David’s age would have been about 70 (2 Sam 5:4). He was sick and unable to keep warm. Abishag the Shunammite girl was brought in to stimulate him. I know of no other way to explain this than that in the folk medicine of the day, it was thought that sexual arousal might stimulate David’s circulation and so warm him. That this is immoral from the New Testament perspective is clear enough, but it was con-sidered an acceptable practice in Old Testament times.2 It is also necessary to the narrative to introduce Abishag because of the way she figures in the later succession struggle.3

2. The struggle for succession continues (Nathan’s prophecy [2 Sam 12:10] about internecine strife comes into play again) (1:5‑53).

a. Adonijah was the fourth son of David and, therefore, considered himself to be next in line for the throne.4

b. Adonijah set out to become king by preparing himself as Absalom had. However, he was undisciplined as a youth, and the writer is telling us that he was unfit to be king. He allied himself with Joab and Abiathar, and excluded Zadok (priest), Benaiah (Head of Bodyguard), Nathan (prophet), and other military officers (1:8‑10).

c. Nathan worked out a plan to get God’s choice, Solomon, on the throne. Bathsheba, David’s favorite wife, was to remind David of his oath about Solomon. She was also to inform David of Adonijah’s plans. Bathsheba carried out the plan and challenged David to rise to the occasion. Nathan came after her to confirm her words (1:11‑27).

d. David responded to the information and took action to enthrone Solomon. He called Bathsheba and reaffirmed his promise to her. He called Zadok, Nathan and Benaiah and charged them to anoint Solomon at Gihon and seat him on David’s throne (1:28‑37).

e. Solomon was anointed and declared king. He rode David’s mule to Gihon where Zadok anointed him, the shophar was blown, and the people received him with rejoicing. A full account of the events was given to Adonijah by Jonathan who fled to the altar for refuge because he feared Solomon. He clung to the altar awaiting assurance from Solomon. Solomon placed him on parole (1:38‑53).5

3. David gives a final charge to Solomon and leaves orders to remove all other obstacles to Solomon’s rule (2:1‑9).

a. David charged Solomon to obey God (2:1‑4).

David stressed the place of the Mosaic law to Solomon in his role as king of Israel. The formula for success is obedience to that law. David reminded Solomon of the importance of the Davidic covenant as it related to the Mosaic law. Obedience to the law brings the blessings of the Davidic covenant.

b. David charges Solomon to deal with certain people (2:5‑9).

David solemnly commanded Solomon to see to it that Joab was executed. David’s relation with Joab is somewhat enigmatic. Joab was David’s nephew but shared few of David’s ideals. He was a strong, efficient military leader, but he also seemed to be without scruples. Thus, he killed Abner by treachery as he later killed Amasa because they both threatened his position as commander of the armies. He had no compunction about dispatching Absalom in spite of David’s orders to the contrary. David seemed to be somewhat in awe of Joab and his brothers (2 Sam 3:39). He complained that they were too hard for him. From the Absalom incident on, David wanted to get rid of Joab, but was apparently unable to do so. On his deathbed he charged Solomon to make sure that Joab was judged for his bloody life (2:5‑6).

Barzillai, David’s wonderful and loyal friend, was to be honored. His descendants were to be allowed to eat at the king’s table (2:7).6

Shimei, who cursed David, was shrewd enough to meet David and to claim to be the first of the Northerners to welcome him back. He candidly admitted his guilt and begged David’s forgiveness. Under those circumstances, David could hardly do anything else. However, he did not forget Shimei’s crime and left to Solomon the task of bringing Shimei’s life to an end (2:8‑9).

4. David dies, and Solomon secures the throne (2:10‑12).

David’s life is succinctly summarized, and it is stated that he was buried in the city of David. We now know that the city of David was the small promontory extending south of the present old city and outside the walls. The tomb of David shown to tourists is on the western hill, which was unoccupied in David’s time. In the Medieval era that section became identified with Zion, and so David’s tomb was “discovered.” However, the tombs of the Judean kings have not yet been located.

Solomon took undisputed control of the kingdom. However, this is a summarizing statement. Before it became actually true, certain loose ends had to be tied up and additional enemies or potential enemies had to be removed.

B. Solomon carries out David’s charges and removes opposition to the throne (2:13‑46).

1. Adonijah makes a foolish request and loses his life (2:13‑25).

a. Adonijah requested Abishag for a wife (2:13‑18).

Adonijah’s action is difficult to understand. A claim to a former king’s concubine was obviously a claim to the throne.7 Why he made the power play at this point is not clear, but it was certainly the wrong thing or the wrong time to do it.

b. Bathsheba passed on the request to Solomon who reacted predictably (2:19‑25).

Bathsheba’s role is also puzzling. She was surely sufficiently experienced in the “Harem battle” to understand the implications of Adonijah’s request, and yet she supported him in it. Is it possible that she was aware of this so as to give Solomon an excuse to get rid of Adonijah? In any event, Solomon read an evil intent into the request and ordered Adonijah’s death.

2. Abiathar is dismissed from the priesthood (2:26‑27).

Abiathar had joined the wrong faction. It is understandable that he would support the next in line only if he were ignorant of God’s promises through Nathan. Zadok stayed on the right side as did the court prophet Nathan. Solomon spared Abiathar’s life because of his relationship with David, but he sent him to Anathoth, his village.8 This dismissal was part of the fulfillment of God’s word to Eli (1 Sam 2:31‑36).

3. Joab is executed for his treacherous acts and because he followed Adonijah (2:28‑35).

Joab knew that his life was over. He had gambled throughout his life in the various palace intrigues that grew with the passing of time. He supported Absalom to a point but killed him when he thought it necessary. In the succession struggle, he presumably thought he could maintain his influence through Adonijah, but he gambled and lost. He fled to the altar as a place of refuge, but Solomon did not spare him. He told Benaiah to kill him as he clung to the horns. Not a very noble way for the old warrior to die! Solomon then appointed Benaiah to Joab’s position as general of the armies.

4. Shimei, who cursed David, is dispatched (2:36-46).

While David was tricked into forgiving Shimei, the cunning peasant, he never personally forgave him and ordered Solomon to find a way to kill him. Solomon set a trap which the avaricious Shimei fell into and was killed by the executioner.

C. God’s blessing on Solomon (Jedidiah) as the legitimate descendant of David is evidenced in Solomon’s commitment to Yahweh and the wisdom granted by Yahweh (3:1‑28).

1. Two introductory observations are made to explain following events (3:1‑2).

a. Solomon’s political alliances were indications of the international sophistication Israel was beginning to take on. However, 1 Kings 11 indicates that this entanglement with foreign powers brought Solomon into the deleterious practice of syncretism. It all began with the alliance with Egypt. Solomon’s bargaining strength is indicated by the fact that Pharaoh sent his daughter to Solomon’s harem. This happened early in Solomon’s reign for his great building projects had not yet begun.

b. The second thing the historian wants us to see is that the people were still using the high places because the temple was not yet built. The disapproval is evident, for he knows all the spiritual implications of the high places and how later it will be necessary to tear them down to maintain the people’s spiritual integrity.9

2. Yahweh reveals himself to Solomon and promises blessing on his rule (3:3‑15).

a. Solomon’s early life was characterized by obedience (3:3‑4).

The historian’s unhappiness with high places is evident in this section. Solomon was a young man who sought to obey the Lord, but he was still offering sacrifices in the high places.10 Solomon made a major sacrificial offering at the beginning of his ministry.

b. Yahweh appeared to Solomon in Gibeon (3:5‑15).

Yahweh gave Solomon the opportunity to ask for anything he wanted. Solomon rehearsed God’s goodness to David and reminded Him of the Davidic covenant (ḥesed חֶסֶד). He humbly confessed his limitations and requested wisdom (ḥokmah חָכְמָה) for service (3:5-9).

God answered in words that indicate the fulfillment of covenant promises: He will give Solomon practical wisdom (חָכְמָה), material blessing, and long life if he obeys. Solomon awoke from the dream and offered sacrifice (3:10‑15).

3. An example of Solomon’s wisdom (ḥokmah) is given (3:16-28).

Wisdom as a way of life and as literature really began with Solomon in Israel. There was certainly wisdom before that time (and Job is a type of wisdom literature), but under Solomon it reached its apex. Solomon was the example, par excellence, of the man with a gift from Yahweh to discern circumstances in such a way as to render good decisions. Books such as Proverbs, Job, Ecclesiastes, and some Psalms discuss wisdom in both theoretical and practical ways.

The case was presented: two prostitutes had children, but one child had died. The mother of the dead child switched children. Solomon must answer the discernment question (ḥokmah): whose was the living child? (3:16‑22).

The case was solved when Solomon discerned that one of the women was the true mother. There was no way to prove it except by drastic measures. Solomon called for a sword to divide the child. The real mother wanted to spare the child. Solomon then had proof and declared her to be the mother of the living child. Everyone acknowledged that God had given ḥokmat Elohim to Solomon (חָכְמַת אֱלהִים) (3:23‑28).

D. The organization of Solomon’s kingdom (4:1‑34).

1. Solomon’s cabinet was similar to David’s (4:1‑6).11

|

Office |

David |

David |

Solomon |

|

|

(2 Samuel 8) |

(2 Samuel 20) |

(1 Kings 4) |

|

Priest |

|

Ira |

Azariah |

|

Secretary |

Seraiah |

Sheva |

Elihoreph/Ahijah |

|

Recorder |

Jehoshaphat |

Same |

Jehoshaphat |

|

Gen. of Army |

Joab |

Same |

Benaiah |

|

Priests? |

Zadok/Ahimelech |

Same |

Zadok |

|

Chief deputy |

|

Azariah |

|

|

Cohen |

Sons |

|

Zahud |

|

Chief Gang |

Labor |

Adoram |

Adoniram |

2. Solomon organized the country into districts (4:7‑20).

David had probably organized the southern part of Israel, so Solomon had the task of organizing the entire country. This involved assigning sub-leaders to various sections to maintain order and provide for the king’s needs.

Each deputy had to supply a month’s provisions (4:7).

Ben-hur—Ephraim

Ben-deker—Makaz, Shaalbim, Beth Shemesh, Elon-beth-hanan.

Ben-hesed—Arabboth

Ben-abinadab—Dor

Baana—Taanach, Megiddo, Beth-Shean

Ben-geber—Ramoth-gilead

Ahinadab—Mahanaim

Ahimaaz—Naphtali

Baana—Asher and Bealoth

Jehoshaphat—Issachar

Shimei—Benjamin

Geber—Gilead (south)

3. Solomon ruled in a time of peace and prosperity (4:21-28).

The first three kings each had a unique contribution to make to Israel’s history. Saul was instrumental in beginning to drive out the Philistines. Only the dark side of Saul is seen in Scripture, but he laid a solid military groundwork for his successors. He showed that the seemingly invincible Philistines could be defeated and provided the opportunity for David to develop as a military leader against the very people whom he would later defeat completely. David brought organization and structure to the kingdom. He also provided a spiritual dimension unknown to either Saul or Solomon. As a matter of fact, David stands out over almost all of his successors. David brought military and political stability to the kingdom. It was left to Solomon to introduce culture and sophistication. For the first time the nation had the leisure, security, and money to pursue the arts and the intellect. Solomon also brought David’s organization to a peak and became the most powerful potentate of his time in that area of the world.

His kingdom extended to the Euphrates.12 He dominated the surrounding kingdoms west of the Euphrates, and they brought him tribute. He developed chariotry and chariot cities. The number in 4:16 is 40,000. 2 Chron 9:25 has 4,000 as does one Hebrew MS for Kings. The lower number is more realistic. The deputies kept him supplied for the abundant needs of the palace.

4. Solomon’s personal ability was extensive (4:29‑34).

a. Solomon was given great wisdom (4:29).

Wisdom (ḥokmah חָכְמָה) (deciding the best course of action);

Discernment (tebunah תְבוּנָה) (problem solving);

Breadth of heart (rohab leb רחַב לֵב) (capacity to embrace diverse compartments of knowledge).

b. His wisdom surpassed that found in Egypt, Ethan, Heman, Calcol and Darda (4:30‑31).

There is a body of wisdom literature from the middle east that goes back beyond the time of Solomon. It is found in Babylonia and in Egypt.

c. His wisdom was in written form (4:32‑34).

He set forth wisdom in proverbs (3000) and songs (1,005) (we have only a few—Psalms 72; 127). He was something of a naturalist.13 Everyone wanted to meet him.

E. Solomon builds the temple and his palace (5:1—9:9)

1. Solomon makes a contract with Hiram to prepare materials (5:1‑18).

Solomon brought from Hiram not only materials and craftsmen, but surely ideas as well. It is now conceded that the temple of Solomon probably looked very much like most other temples of his day. It is a bit ironic that a pagan king and country should furnish the people and material to build the temple of Yahweh when the tabernacle was built by spirit-gifted individuals from Israel.

2. Solomon constructs the temple (6:1‑38).

a. The temple construction began in the fourth year of Solomon’s rule, which was the four hundred eightieth year after Israel had come out of Egypt. This date is the anchor for the chronology that places the exodus at 1441 BC plus or minus a few years. Those who would argue for a thirteenth century date for the exodus must treat this reference as a round number of twelve times forty.

b. The temple was built more or less on the pattern of the tabernacle. It consisted of a holy place and a holy of holies that was cubic in structure. The furniture was similar: laver, lampstand, ark of the covenant, etc., but the style was quite different. The more recent depictions of Solomon’s temple, e.g., the reconstruction in the model of Jerusalem, follow middle eastern styles in general and are probably more accurate than the older ones.

3. Solomon constructs his palace (7:1‑12).

Solomon’s palace must have been magnificent. It took thirteen years to build the palace whereas the temple took seven years. This building project necessitated expanding the city to accommodate these immense architectural additions. The city was expanded north and a huge retaining wall and platform were built. Herod expanded this platform when he rebuilt the temple.

4. A recapitulation is given of the fine work of the temple (7:13‑51).

A certain Tyrian-Israelite artisan supervised the vast amount of casting and carving done on the temple. The value of the temple would be impossible to calculate, but it must have been immense. The riches of this building would always be a temptation to kings, and more than once in the future, its walls would be stripped to buy off the latest marauder.

5. Solomon dedicates the temple (8:1‑66).

a. The priests moved the ark from the tent in the city of David and brought it to the temple. It was deposited in the holy of holies and God’s presence was manifested with the glory cloud filling the temple (8:1‑11).

b. Solomon addressed the assembly stating the reasons for the building of the temple and David’s part in it.

c. Solomon prayed to the Lord and rehearsed again the elements of the Davidic covenant. He then laid out the importance the temple would play in the lives of the covenant people: sin would be revealed, drought would be prayed for, famine would cause them to come before God, foreigners would be awed by it, Israel would pray when they went out to battle, in captivity they would turn toward the temple (8:12‑53).

d. Solomon then blessed the people and prays that all will acknowledge that there is only one God (8:54‑61).

e. For seven days Solomon offered sacrifices and peace offerings. On the eighth day he dismissed the people with happy hearts (8:62‑66).

6. God accepts the dedication (9:1‑9).

In the words of the Davidic covenant, Yahweh told Solomon that he would bless him if he walked in obedience. However, if his seed should fail to obey God, then they could only expect the judgment of God in their lives.

F. Solomon settles with Hiram (9:10‑14).

Solomon paid Hiram in cities, giving him twenty in the land of Galilee, but Hiram was not pleased with them. He called them cabul (כָּבוּל) which may mean “as nothing.”14 Verse 14 can only make sense as a pluperfect: Hiram had given Solomon 120 talents of gold. Solomon probably had borrowed this money to help in the extensive building projects, which probably cost more than even wealthy Solomon could raise. Solomon presumably had expected to repay the money with the twenty cities. Chronicles (1 Chron 8:2) indicates that Hiram refused the cities, so Solomon would have had to repay the loan with later revenue.

G. A list of activities and accomplishments is given (9:15‑28).

Like his successor, Herod, a millennium later, Solomon engaged in almost frenzied building activity. The most significant projects were the temple and the palace, but Solomon also built and refortified many cities. Excavations at Hazor (north), Megiddo (north central) and Gezer (south) have turned up similar gateways coming from the Solomonic period.15 These cities controlled the passes coming into Palestine. The stables at Megiddo once attributed to Solomon are now attributed to Ahab, but the structures would have been similar. The narrow ridge on which the Jebusites built their city was not adequate for expansion. The “millo” may be terraced walls for added construction.16

H. Solomon’s wisdom brings renown and wealth (10:1‑29).

Solomon prayed for wisdom in chapter 3, and an example of that wisdom was given when he arbitrated the dispute of the contesting mothers. God’s other promise was material prosperity. This too was illustrated with the coming of the Queen of Sheba.

1. The Queen of Sheba (10:1‑10).

a. The amazing story of the Queen of Sheba has caught the fancy of many people through the centuries. The Ethiopians argue that Sheba is to be identified with Ethiopia and that Solomon and the queen carried on a dalliance that produced the beginning of the monarchy that was still in existence in modern times in Haile Selassie (strength of the trinity). She was probably from the Arabian coast, however, and had heard of Solomon through his trading expeditions.

b. She tested him in riddles, saw his opulence and came away saying she had only heard half of the story. She gave him an appropriate gift.

2. Solomon’s trade (10:11‑29).

Solomon’s vast international trade (maritime and overland) made him fabulously wealthy. Gold was so common it made silver insignificant. We hear that Solomon was both wealthy and wise, but his wisdom was insufficient to prevent him from falling into apostasy.17

I. Solomon falls in spite of his wisdom (11:1‑43).

1. The occasion for the fall was his international marriages (11:1‑8).

a. Solomon’s destruction began with the political alliances sealed with marriages. He was allied with Egypt, Moab, Ammon, Edom, Sidon, and the Hittites. We have discussed “loved” previously in connection with Amnon. This does not mean romantic love, but the choice of a person. Solomon chose to cement his political relations with intermarriage, so much a part of the culture of that day (11:1‑2).

b. Solomon had 700 wives and 300 concubines. Each foreign wife would have brought her retinue of priests. In deference to the various countries, Solomon built shrines to their deities. He then became ensnared in them himself (11:3‑4).

c. The deities Solomon worshipped were Ashtoreth of the Sidonians; Milcom /Molech18 of the Ammonites; and Chemosh of the Moabites. There were many more deities represented in Jerusalem, but these are the best known and seemed to have the deepest impact on the people of Israel. This was particularly true of Milcom/Molech because children were sacrificed to him (11:5‑8).

2. God judged Solomon because of this syncretism (11:9‑40).

a. The historian certainly admires Solomon for his wisdom, prosperity and in particular for building the temple. However, this does not prevent him from painting Solomon in the garish colors of his spiritual apostasy.

b. Yahweh was angry with Solomon because He had appeared to him twice and had ordered him to avoid such practices. “To whom much is given, much is required.” As a result, Yahweh promised to tear the kingdom from his son and to leave only one tribe (11:9‑13).

c. Yahweh began to raise up adversaries; the first was Hadad of Edom who had fled to Egypt in David’s time (11:14‑22).

d. The second adversary was an Aramean named Rezon. He took advantage of the vacuum left by David’s death to rule in Damascus (11:23-25).

e. The third adversary was Jeroboam who would one day become the king of the northern tribes. This young man was appointed an overseer of the forced labor used to build Millo. The prophet Ahijah from Shiloh told him through symbolic action that he would receive the majority of the kingdom. He was told that if he obeyed God, he would have an everlasting dynasty like David’s. The prophet also told him that one tribe would be left for David in accordance with the Davidic covenant (11:26‑40).

3. Solomon’s death is recorded after a forty-year reign over Israel.

The source for much of the material in this first book of kings comes from the Acts of Solomon, a non-extant book. An apparently smooth transition was accomplished with his son Rehoboam (11:41‑43).

II. Divided Kingdom—Rehoboam/Jeroboam to Jehoshaphat/Ahab (12:1—16:34). (The first eighty years—931‑850 BC)

[From here on the northern kings will be in italics.]

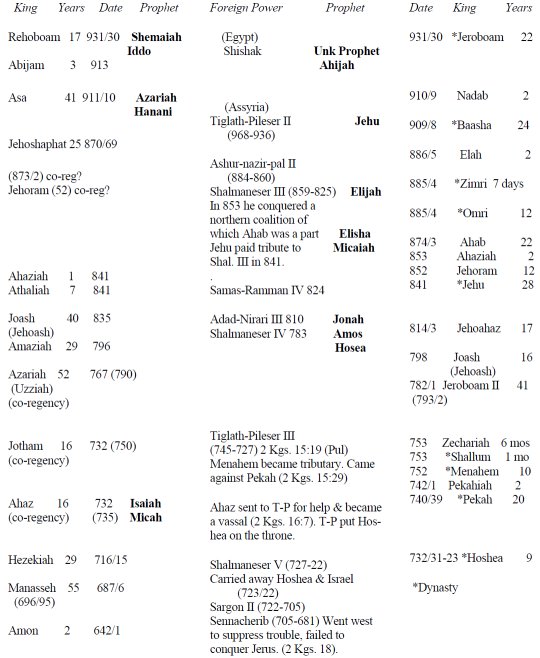

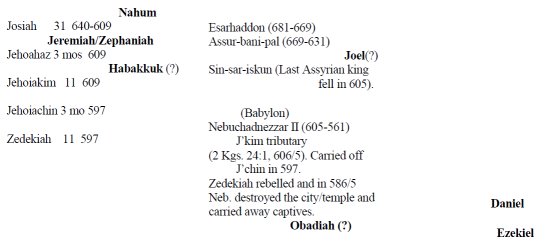

The centrifugal force has now overcome the centripetal force. The rupture has taken place. The northern kingdom will have a leadership that is essentially ungodly from Jeroboam I until the last king Hoshea. Only six kings in Judah will be considered godly men. The chronology of this era is very difficult because of the lack of an absolute chronology, different methods of reckoning ascension years, to say nothing of co-regencies of father and son and dual regencies.19 The attached chart is to help visualize the period of the monarchy. See p. 258.

A. The rupture of the kingdom under Rehoboam (12:1‑33).

1. The foolish decision of Rehoboam cost him the northern tribes (12:1‑15).

a. The succession seemed to be fairly smooth. Rehoboam went to Shechem to be made king.20 Jeroboam had fled to Egypt (11:40) where he heard of Solomon’s death and returned. (Follow the reading in 1 Chron 10:2. The Hebrew “he was living” and “he returned” look the same without vowels) (12:1‑2).

b. The people challenged Rehoboam to change the policies of his father (remember what Samuel told them would happen, 1 Samuel 8?). Rehoboam consulted with the elders who advised him to listen to the people. Rehoboam asked his young peers what he should do, and they advised him to be hard on the people. Rehoboam told the people he would be even harsher than his father was (12:3‑14).

c. The historian tells us that all this was in accord with God’s purpose in removing part of the kingdom from Solomon as he had predicted through Ahijah the Shilonite (12:15).

2. Rehoboam’s foolish act prompted the northern tribes to break off (12:16‑20).

The Israelites in the north returned home and made Jeroboam king. The rebellion was made permanent when the chief of the gang labor was stoned to death, and Rehoboam barely escaped with his life.

3. Rehoboam was dissuaded from trying to restore the ten tribes by force (12:21‑24).

Rehoboam gathered his army, determined to prosecute the war against Israel. Shemaiah, the prophet, warned them that this rebellion was from the Lord, and they must not fight. The civil war was avoided.

4. Jeroboam instituted a religious system to keep the Israelites from going to Jerusalem (12:25‑33).

a. He rebuilt Shechem, an ancient town going back to the patriarchs, along with Penuel. Jeroboam worried about Israel being enticed to return to Jerusalem (the centripetal force) and so made two golden calves which he set up in the ancient cult center of Bethel and in the extreme north in Dan (12:25‑30).21

b. He built temples on the high places and ordained priests from the non-Levitical families.22 He instituted a feast in the eighth month to rival the feast in Jerusalem (did the grain ripen later in the north or was this to make the break sharper?). He was burning incense on the altar (12:31‑33).

Saul (40?) (1051-1011) Samuel

David 40 (1011-971) Nathan

Solomon 40 (971-931) Gad

B. God sent an anonymous prophet to speak against the altar (13:1‑32).

1. The prophet spoke against the altar and was vindicated by God (13:1‑10).

a. He said that a king by the name of Josiah would rise up to destroy the altar (Josiah ruled from 640‑609 B.C. This prophecy was almost 300 years prior to the event. See 2 Kings 23:15‑18 for the fulfillment). He stated that God would give a sign to validate the message. King Jeroboam stretched out his hand to order the prophet arrested, and his arm was miraculously stiffened. The sign of the ruptured altar was given simultaneously (13:1‑4).

b. The king asked the prophet to pray for him which he did, and the king’s arm was restored. The king tried to persuade the prophet to go home with him, but he said that he was divinely prohibited from going anywhere but back to Judah. The prophet left to go home a different way from the way he had come (13:5‑10).

2. The prophet is enticed to go home with an old prophet in Bethel (13:11‑19).

There was an old prophet living in Bethel who heard the story from his sons and went after the prophet to invite him home. The prophet refused, saying that Yahweh had prohibited it. The old prophet then told him that Yahweh had revealed himself to him and told him to bring the prophet home with him.

3. God judged the prophet for disobeying him (13:20‑32).

God used the lying prophet to bring the message of judgment upon the prophet from Judah. A lion killed the man of God. The lying prophet brought his body back and told the boys he wanted to be buried with him because he knew God would fulfill the word spoken through him.23

C. Jeroboam was not sufficiently affected to change spiritual directions, and his sin became a perpetual stumbling block in the history of the northern kingdom (13:33‑34).

D. God gave to Jeroboam a message of judgment through Ahijah the prophet (14:1‑20).

1. Jeroboam’s son Abijah was sick (14:1).

2. Jeroboam wanted help from Ahijah, but he was afraid to face him directly (14:2‑5).

He told his wife to disguise herself. What made these kings think they could hide from God?24 Yahweh revealed to Ahijah that Jeroboam was sending his wife to him and that she would be disguised.

3. Ahijah delivered his message of judgment to Mrs. Jeroboam (14:6‑16).

Ahijah recited what God had done for Jeroboam and yet Jeroboam had rejected God. Because of that apostasy, Jeroboam’s family would be judged severely, and that judgment would begin with the son of Jeroboam. God was going to raise up a king for himself who would cut off the house of Jeroboam. Furthermore, Israel would also be judged and sent into captivity beyond the Euphrates because she followed Jeroboam

4. Jeroboam’s wife returned home, and the child died as predicted (14:17‑18).

5. Jeroboam died (14:19‑20).

This first king of the northern tribes, an Ephraimite, ruled twenty-two years, a rather long reign. His contribution to Israel nationally was fairly significant. What he did religiously was to reinforce the tendency to syncretism already found in this people so greatly influenced by the Gentiles around them. The rival worship centers, however much they might be related to Yahweh (as some scholars contend), were images of the bull, the symbol of fertility throughout the middle east, and were instrumental in leading Israel farther from Yahweh.

E. Rehoboam’s career did not exemplify godly characteristics (14:21‑31).

1. Judah’s spiritual state is abysmal during his reign (14:21‑24).

a. Rehoboam was forty-one at his ascension and he reigned seventeen years. The historian puts great stress on the fact that Yahweh chose the city of Jerusalem over all other sites for the temple. This is an editorial comment against the high places throughout Israel.

b. Judah began to decline under Solomon. That decline increased under Rehoboam. There were high places: (bamoth בָּמוֹת) sacred pillars: (maṣṣeboth מַצֵּבוֹת); Asherim (אַשֵׁרִים); and male cult prostitutes: (qodeshim קָדֵשִׁים).

2. The Egyptians under Shishak invaded Judah and robbed the temple (14:25-28).

a. Shishak was a Libyan who had risen in the ranks of the Egyptian army until he was able to become Pharaoh, bringing in the 22nd dynasty. He invaded Judah and Israel even though he had given asylum to Jeroboam (14:25-26).25

b. Rehoboam substituted bronze shields for the gold ones, which had been plundered. This was the beginning of a succession of acts of plunder of the temple (14:27-28).

3. Rehoboam died and so concluded a reign marked by mediocrity and war between him and Jeroboam. His son Abijam became king in his place (14:29-31).

F. Abijam’s (Abijah) reign was characterized by the same sinful practices of his father (15:1‑8).26

1. Abijam had a short reign of three years.

His mother was Maacah the (grand)daughter of Abishalom. Assuming this man is the son of David, Maacah would have been the daughter of Absalom’s only daughter, Tamar, who in turn was married to Uriel (see 2 Chron 11:20; 13:2) (15:1‑2).

2. Abijam was as sinful as his father Rehoboam had been (15:3‑6).

a. His “heart was not wholly devoted to Yahweh” (15:3).

b. God still allowed him to be king because He was honoring the Davidic covenant. It is for David’s sake who was a godly man in spite of his great sin against Uriah the Hittite (15:4-5).

c. The wars begun by his father against Jeroboam continued under Abijam (15:6).

3. Abijam finished his reign with no notable contribution (15:7‑8).

G. Asa broke the pattern of his predecessors and sought to please Yahweh (15:9‑24).

1. Asa brought a certain amount of reform to Judah (15:9‑15).

a. He ruled forty-one years and his (grand)mother’s name was Maacah. (Maacah is mentioned because of her prominence and because she was removed from the Queen Mother’s position) (15:9‑10).

b. Asa proceeded to remove paganism. He even removed his grand-mother because of her paganism (15:11‑13).

c. Asa did not remove the high places, because they were probably not yet looked upon as being pagan even though they no doubt were in fact. He did embellish the temple (15:14‑15).

2. Asa carried on war with Baasha (Israel) (15:16‑22).

Baasha was able to control Ramah, about ten kilometers north of Jerusalem, which indicates Asa’s weakness militarily. Asa began the bad practice of hiring outside military help; in this case Ben-Hadad, the Aramean king in Damascus.27 The treaty worked. Northern pressure caused Baasha to back off from Ramah. Asa tore down the fortifications and refortified other cities.

3. Asa died with foot disease, and Jehoshaphat reigned in his place (15:23‑24).

H. Nadab ruled in the north in the place of his father Jeroboam (15:25‑31).

1. Nadab ruled only two years and was an evil king (15:25‑26).

2. Baasha, an army officer, became king (15:27‑30).

It seems as though near anarchy was prevailing. While Nadab was besieging an enemy city, an army officer by the name of Baasha treacherously killed him. He then proceeded to kill all the household of Jeroboam, and thus God’s word through Ahijah was fulfilled (14:9‑10).

I. Baasha was a wicked king who incurred God’s judgment (15:32—16:7).

1. He fought against Asa in the south as we have already seen. God pronounced judgment against him through Jehu son of Hanani: God will judge Baasha as He judged Jeroboam (15:31—16:4).

2. Baasha died, and his son Elah ruled. God’s judgment came upon Baasha’s family because of his personal sin, and because he carried out God’s judgment against Jeroboam (offenses must come, but woe to the one by whom they come) (16:5‑7).

J. A period of bloody civil war follows in Israel’s history, in which God judges the house of Baasha (16:8‑28).

1. Elah reigned two years in Tirzah. While in a drunken stupor, he was killed by one his officers, Zimri (16:8‑10).

2. Zimri then wiped out the family of Elah (Baasha) as God had predicted (16:11‑14).

3. Zimri only lasted seven days because another officer was made king (in the ongoing siege against Gibbethon) (16:15‑20).

Omri and his men besieged the capital of Tirzah, and Zimri killed himself (16:19‑20).

4. Omri prevailed in the civil strife that followed (16:21‑28).

A certain Tibni took part of the people, but Omri was able to kill him. Omri ruled six years at Tirzah and then moved the capital to a new city called Samaria. Omri was a very wicked king.28

K. Ahab, a powerful king, came to the throne, and the stage was set for his confrontation with the prophets of Israel (16:29‑34).

1. Ahab ruled Israel for twenty-two years in Samaria and was pro-nounced by the historian to be worse than all his predecessors. He was personally wicked (16:29-30).

2. Ahab’s crowning evil was to bring in the Sidonian princess Jezebel, daughter of Ethbaal, who became an aggressive missionary for Baal.29 These were thoroughgoing Baal worshippers (16:31).

3. Ahab became a follower of Baal, building him a temple and erecting an altar in it. He also built Asherim as well (16:32‑33).30

L. God’s curse on Jericho, given in Joshua’s day, was carried out at this time (16:34).31

III. Divided Kingdom—Elijah versus the dynasty of Ahab and Jezebel (17:1—2 Kings 1:18 [874‑853 BC])

Samuel, Nathan, and Isaiah were closely related to the royal court, that is, they were in almost an advisory capacity. There was never any question as to who spoke with the greater authority—that was the prophet, but there was a greater sense of cooperation than seems to be true later. That cooperation no doubt grew out of the spiritual sensitivity of the kings to whom the prophets were ministering. In any event, prophets such as the unknown man who spoke against the altar of Jeroboam, Micaiah, Jeremiah, and, most of all, Elijah carried on an adversarial relationship. Ahab will say “Have you found me, Oh my enemy?”

Elijah holds a great place in biblical history. His name is consonant with his message: Yahweh is God (אֵלִיָּהוּ). Malachi predicts that he will come before “the great and terrible day of Yahweh” (Mal 4:5). As a result, the Jews were looking for Elijah and even asked John the Baptist if perchance he were Elijah (John 1:25). The people of Jesus’ day assumed that, among other possibilities, Jesus may have been Elijah (Matt 16:14). It is Elijah who appeared with Jesus before the chosen three on the Mount of Transfiguration (Matt 17:3) and prompted the disciples to ask Jesus about the coming of Elijah. Jesus’ reply was that John the Baptist, coming in the spirit and power of Elijah, was in a sense Elijah. But Elijah must yet come (Matt 17:9‑13).

This “Elijah cycle” (17:1—22:40) is unusual in that it centers on the northern kingdom. The rest of the book emphasizes Judah. These long narrative accounts involve Elijah as God’s spokesman to the wicked house of Ahab.

A. God spoke through His prophet Elijah to bring a famine on the land to punish Ahab and then protected his servant (17:1‑24).

1. The proclamation of the famine is given to King Ahab (17:1‑7).

a. Elijah was called the Tishbite (NASB does not treat this as a proper noun. “Settlers” is deriving it from the Hebrew yašab [יָשַׁב]), and his country was on the east side of the Jordan in Gilead. Elijah proclaimed that there would be neither rain nor dew for a period of time (the time is known later as three years). It is important to note that Baal is the storm god and the fertility god. He should be the one to bring rain in the time of drought. Yahweh was therefore challenging the entire religious system of Baalism (17:1).

b. Yahweh then sent Elijah to a place where he would be safe and provided for him. He showed His control over nature by sending the ravens to feed him. In the natural course of events, the brook dried up because of the drought (17:2‑7).

2. Yahweh sent him to Zarephath, a Sidonian city, to preserve him (17:8‑16).

a. Elijah was now outside the boundaries of Ahab’s control, and God also had a widow woman to take care of him there. (Her reference to “Yahweh your God” [v. 12] indicates that she at least knew about Israel’s God.) Jesus makes a point of the fact that during the famine, Elijah went to only one widow, and she was a Sidonian (Luke 4:24‑26) (17:8‑9).

b. Elijah performed a miracle, which convinced the widow of his genuineness (17:10‑16). (The miracle also provided them with food for the duration.)

3. Elijah healed the widow’s dead son and further convinced her of his position as representative of Yahweh (17:17‑24).

The widow’s only child became sick and died. She blamed Elijah because she assumed his godly presence had caused a holy God to judge her. Elijah prayed for Yahweh to heal the boy, and he answered his prayers. The woman then testified strongly that Elijah was a man of God, and that the word of Yahweh was in his mouth. This great testimony came from a Gentile of Sidon.

B. Yahweh challenged the Baal prophets through Elijah and vindicated himself (18:1‑46).

1. Yahweh sent Elijah to confront Ahab and tell him that He would bring rain (18:1‑6).

Three years had lapsed since Elijah had told Ahab there would be no rain. Elijah was to proclaim that Yahweh would bring rain on the earth (not Baal). Ahab and his steward Obadiah were looking for water (this Obadiah [servant of Yahweh] protected a hundred prophets of Yahweh when Jezebel was trying to exterminate them).

2. Elijah met Obadiah and told him to inform Ahab of his presence (18:7‑15).

Obadiah feared that Elijah would be gone when he returned with Ahab, and that he would suffer the consequences. Ahab had looked everywhere for Elijah to kill him, (apparently it was common know-ledge that the Spirit of God moved Elijah around), but Elijah assured him that no harm would come to him (18:15).

3. Elijah threw down the gauntlet to Ahab (18:16‑19).

Ahab blamed Elijah, but Elijah charged him with forsaking the commandments of Yahweh and following Baal (how easily we blame others when in reality it is our refusal to follow the Lord that is the reason for the problem). Elijah challenged Ahab to bring 450 prophets of Baal and 400 prophets of Asherah to meet him at Mt. Carmel. These were all subsidized, professional prophets.32

4. Elijah squared off with the 450 prophets of Baal before the people (18:20‑24).

Elijah challenged the people to choose between Yahweh and Baal. Elijah then fixed the ground rules—two oxen, two altars, two gods. The test was to see who the true god of the storm was.

5. The prophets of Baal went through all their ritual but were unable to bring rain (18:25‑29).

Their worship included dancing and self-mutilation. Elijah mocked them as they tried futilely to get Baal to answer.

6. Elijah proved that Yahweh was the God of rain and fruitfulness (18:30‑40).

a. Elijah repaired an existing altar of Yahweh, which had been torn down, emphasizing repeatedly the name Yahweh, and the covenant of Yahweh (18:30‑32).

b. He dug a trench around the altar and had the sacrifice drenched with water (from the Mediterranean Sea), then prayed in the hearing of all the people, emphasizing that Yahweh was the ancient God of the patriarchs, and that Elijah was His spokesman (18:33‑37).

c. God answered with a miraculous fire that caused the people to acknowledge that Yahweh was God (18:38‑39).

d. Elijah killed the 450 prophets of Baal (18:40).

7. Elijah predicted that Yahweh would now bring the promised rain (18:41‑46).

a. He told Ahab to eat and drink, then he went to look for the water-bearing cloud which appeared after seven trips by the servant (God seems to test people on occasion by forcing them to wait) (18:41‑44).

b. Ahab harnessed up the chariot to go to Jezreel before the rain caught him. Elijah in the power of Yahweh outran the chariot to Jezreel (18:45‑46).

C. Elijah, Yahweh’s servant, became discouraged because he thought victory had been turned into defeat (19:1‑21).

1. Jezebel sent messengers threatening Elijah’s life. She was not the slightest daunted by the great victory on Carmel nor in the death of so many of her prophets (19:1‑2).

2. Elijah fled for his life (19:3‑8).

a. The word “life,” Hebrew nepheš (נֶפֶשׁ), can mean life, but here probably means “soul” or his innermost being. Elijah was not fleeing because he was frightened (otherwise he would not have had to go as far as he did), but because he was defeated (19:3).33

b. He traveled south in the Negeb and pleaded with God to kill him. Elijah had spent a grueling day on Mt. Carmel; he had run all the way to Jezreel; and now he had come all the way to the Negeb and taken another day’s journey into the wilderness. He was psychologically and physically worn out (19:4).

c. God encouraged His weary and defeated servant by giving him food and rest. How gracious of God to nourish and sustain before trying to discipline (19:5‑7).

d. Elijah then traveled forty days into the wilderness. The distance is not that far to Horeb, so he must have “wandered” as the Israelites did. Elijah was on a pilgrimage (19:8).

3. Yahweh confronted His servant in the same place He confronted Moses (19:9‑14).

a. Elijah came to “the” cave (hamme‘arah הַמְּעָרָה).34 Yahweh asked Elijah what he was doing there, and Elijah complained that he alone served Yahweh (9:9‑10).

b. Yahweh told Elijah to stand on the mountain where a wind, an earthquake, and a fire occurred.35 Yahweh did not manifest himself in the spectacular events. He revealed Himself as a still, small voice. Yahweh then asked the same question of Elijah and got the same answer (19:11‑14).

It seems that Elijah went back to the place Yahweh had met with Israel to make a covenant. Elijah ate divinely provided food, roamed forty days in the wilderness, he came to Mt. Horeb (Sinai), he came to “the” cave, and phenomena of nature appear similar to that in Exodus 19‑20. God was gently letting His servant know that circumstances are still in His control. The similarity between Elijah and Moses is not accidental:

|

Moses (Exodus 33) |

Elijah (1 Kings 19) |

|

1. People had gone after calves. |

1. Israel had gone after Baal. |

|

2. Moses interceded. |

2. Elijah believed he was alone representing God. |

|

3. Moses wanted to see God’s glory. |

3. God showed His glory to Elijah. |

|

4. God hid Moses in a niche. |

4. Elijah came to the cave. |

|

5. Israel was at Mt. Sinai. |

5. Elijah came to Mt. Sinai. |

|

6. Israel wondered forty years. |

6. Elijah “wandered” forty days and nights. |

4. Yahweh recommissioned Elijah and sent him back (19:15‑21).

First, God told Elijah to go to Syria and anoint Hazael to be the next king (this showed that Yahweh was in charge even in foreign countries). Secondly, He told Elijah to anoint Jehu king over Israel (this showed that He would punish the house of Ahab). Thirdly, He told Elijah to anoint Elisha to take his place (this showed that Elijah was not indispensable). Yahweh also reminded Elijah that he was not alone in the task. Elijah carried out the third part of the commission. The other two were implemented by his successors who represented him.

D. Yahweh proved His universality by giving Ahab continuous victory over the Arameans (20:1‑29).

The historian’s attitude toward the wicked house of Ahab is indicated in his treatment of his history. Chapter 16 introduces him historically with his evil wife Jezebel. His name is used six times. Chapters 17 through 19 record the confrontation between Ahab/Jezebel and Elijah. His name appears eighteen times in these three chapters (sixteen in chapter 18). Chapter 21 recounts his evil act against Naboth, and his name is used fifteen times. The 22nd chapter tells of his alliance with Jehoshaphat (condemned in Chronicles), but his name does not appear until v. 20 where God pronounces judgment on him. Later in the chapter the normal chronicle note is given of his death and his successor. Ahab’s name occurs in 2 Kings some twenty-seven times either in a straightforward chronicle statement or in a pejorative context. Chapter 20 is the only chapter that presents an account of Ahab that is favorable or at least neutral. In this chapter he is the king of Israel, God’s chosen people. A foreign king is besieging God’s people, and God delivers them. The armies of Ahab are weak, and they are being confronted with an impossible situation, but God is on their side. This chapter shows the generally capable leadership of Ahab as king of Israel, but of course we know from the other chapters that he was morally bankrupt. It is as though the historian cannot bring himself to talk about this king by name. He used his name in v. 1 when the story began and in vv. 13, 14 where the prophet came to him. Otherwise, he refers to him as “the king of Israel.” This chapter probably does not come from the “Elijah cycle.” Elijah is not mentioned, but the prophets who are featured are no doubt part of the “school of the prophets.”

1. Ben-Hadad in a coalition of thirty-two kings besieged Samaria and demanded total capitulation (20:1‑6).

Ben-Hadad36 besieged the city into which Ahab had fled because he was unable to fight the Syrian coalition in the open field. When Ben-Hadad demanded silver, gold, wives, and children, Ahab had no option but to concede.37

2. Ahab refused an impossible demand (20:7‑12).

Ben-Hadad arrogantly demanded that since everything belonged to him, he should be able to search the houses for what he wanted. Ahab and the elders refused this excessive demand.38

3. A prophet of Yahweh told Ahab that He would deliver the Arameans into his hand (20:13‑15).

Ahab was morally bankrupt, but because he was the king of God’s people, God sent him a prophet with a message of great encouragement.

4. Ahab won a great victory (20:16‑21).

God told Ahab to send out the “squires of the commandants.”39 These men formed the vanguard that the Syrians considered harmless, but they killed those who came out to meet them. Then Ahab released the seven thousand he was holding at the gates, and there was a great victory over the drunken Syrians.

5. A prophet of Yahweh warned Ahab that there would be another war and that Yahweh would give them victory to show that He is not geographically limited (20:22‑25).

6. Ahab won another great victory the next year (20:26‑30).

The Arameans reorganized their army.40 They argued polytheistically that Yahweh must be a God of the mountains,41 therefore, they would fight them in the plain. They mustered at Aphek and were decisively defeated. Ben-Hadad escaped to Aphek where he hid in an inner room.

7. Ahab foolishly made a covenant with Ben-Hadad and spared him (20:31‑34).

Ben-Hadad’s advisors negotiated a surrender of their king to Ahab who chose to spare him, made a covenant with him, and sent him home.

8. A prophet of Yahweh told Ahab that he would lose his life because of this indiscretion (20:35‑43).

This entire incident presumes that this Aramean battle was declared by Yahweh to be a ḥerem war. In v. 42, the phrase “devoted to destruction” (ḥerem חֶרֶם) occurs. Like Saul before him, Ahab failed to carry out the conditions of the war and incurred the judgment of God. He was told that he would die because of this disobedience.

Sometime in this era, a famous battle took place in which Ahab allied with the Arameans to fight against Assyria. It is called the Battle of Qarqar (Karkar) and was fought in 853 BC. Shalmaneser III was the King of Assyria. He says: “I departed from Argana and approached Karkara. I destroyed, tore down and burned down Karkara, his royal residence. He brought along to help him 1,200 chariots, 1,200 cavalrymen, 20,000 foot soldiers of Adad-’idri (i.e. Hadadezer) of Damascus, 700 chariots, 700 cavalrymen, 10,000 foot soldiers of Irhuleni from Hamath, 2,000 chariots, 10,000 foot soldiers of Ahab, the Israelite, 500 soldiers from Que, 1,000 soldiers from Musri, 10 chariots, 10,000 soldiers from Irqanata, 200 soldiers of Matinu-ba’lu from Arvad, 200 soldiers from Usanata, 30 chariots, 1[0?[,000 soldiers of Adunu-ba’lu from Shian, 1,000 camel‑(rider)s of Gindibu’, from Arabia, [. . .],000 soldiers of Ba’sa, son of Ruhubi, from Ammon—(all together) these were twelve kings. They rose against me [for a ] decisive battle. I fought with them with (the support of) the mighty forces of Ashur [god], which Ashur, my lord, has given to me, and the strong weapons which Nergal [god], my leader, has presented to me, (and) I did inflict a defeat upon them between the towns of Karkara and Gilzau.”42 We know from the chronology, that the year 853 BC was the year of Ahab’s death. However, he did not die in this Assyrian battle, but in the battle with the Arameans in chapter 22. These two battles, therefore, one allied with the Arameans and one against them, were fought in the same year.

E. Yahweh demanded justice of Ahab and Jezebel for the wicked acts com-mitted against Naboth in taking his inheritance and his life (21:1‑29).

1. Ahab wanted an adjacent vineyard, but its owner refused to sell it to him (21:1‑4).

Ahab’s primary residence was in Samaria, but he had a royal residence in Jezreel as well (cf. 1 Kings 18:45). Adjacent to this property was a vineyard belonging to a certain Naboth. Ahab rather petulantly tried to buy or trade for this vineyard. Naboth refused, following the old Mosaic code of the land staying in the patrimony. Ahab went home angry and pouting.

2. Jezebel took action to acquire the vineyard for her husband (21:5‑16).

Jezebel, a stubborn, selfish, but decisive woman set events in motion to acquire the vineyard for Ahab. This required that false witnesses be hired against Naboth. The letters had to be sent because she was in Samaria. Naboth was stoned to death on the thinnest of trumped-up charges. Ahab at his wife’s behest went to take the vineyard.

3. Yahweh sent Elijah to confront Ahab (21:17‑24).

Elijah predicted the death of Ahab and of Jezebel, saying that the dogs would lick his blood and eat her. His dynasty would be like that of Jeroboam and Baasha. These are the only two predecessors of Ahab of whom it could be said that they had a dynasty. Jeroboam ruled twenty-two years, and his son Nadab ruled two years. Baasha ruled twenty-four years and his son Elah ruled two years. Zimri does not count for he only ruled seven days and had no children succeed him. This was Yahweh’s judgment pronounced on this family that tried so ardently to impose the religion of Baal in Israel and to persecute those who stood true to Yahweh.

4. The historian inserted a statement indicating the extent of Ahab’s sin (21:25‑26).

Jezebel is charged with inciting Ahab to his sin. She does appear in the accounts to be the stronger person. Ahab himself withstood Elijah, and was therefore completely culpable, but at times (e.g., after the Carmel experience) he seemed somewhat willing to submit to Yahweh.

5. Ahab repented and God promised to postpone the judgment (21:27‑29).

Because of a genuine attitude of repentance in Ahab, Yahweh told Elijah that he would postpone the judgment on his house to a later day. Jehu carried it out.

F. Yahweh brought final judgment upon Ahab through the word of the prophet Micaiah (22:1‑40).

1. Ahab and Jehoshaphat formed an alliance (22:1‑4).

Jehoshaphat was essentially a godly king. However, he chose ill-advisedly to join with Ahab in a war with the Arameans. There had been a three-year lapse since the last war with the Arameans. Ramoth-gilead had been taken by the Arameans and Ahab wanted to recover it. Jehoshaphat agreed to join fully with him.

2. Jehoshaphat asked Ahab to inquire of Yahweh (22:5‑12).

a. Jehoshaphat was a thoroughgoing worshipper of Yahweh. Ahab, on the other hand, was syncretistic. He had not yet learned the lesson of Carmel. He was surrounded by a coterie of prophets who were supported by the king and therefore told him what he wanted to hear. In response to Jehoshaphat’s request to seek Yahweh’s mind in the matter, Ahab assembled the prophets. Ahab did not mention the name of Yahweh; he simply said, “Should we go up to war or not?” Their first response did not use the name Yahweh but the generic term Adonai (אֲדנָי) or Master that could be used of any deity.43 It was only after Jehoshaphat’s displeasure with their prophecy became evident that they began to use the name Yahweh (22:5‑6).

b. The prophets of Baal assured Ahab he would win. Jehoshaphat, apparently becoming uneasy at this display put on by prophets, asked whether there was a prophet of Yahweh there. Ahab acknowledged Micaiah (“who is like Yahweh”), but said that he hated him (22:7-12).

3. Micaiah was brought to Ahab with the admonition not to “rock the boat” (22:13‑28).

a. Micaiah first answered with sarcasm. The ready availability of Micaiah and his return to prison at the end of the interview probably indicate that he was in prison all along. This would demonstrate Ahab’s attitude toward true prophets of Yahweh. Micaiah, knowing what the other prophets were saying, sarcastically added his vote to theirs: “Go up and succeed for Yahweh will give it into your hand.” The obvious tone of voice caused Ahab to demand a true response (22:13‑16).

b. Micaiah, in sober tones, predicted that Ahab would be killed in battle. When Ahab rejected the message, attributing it to Micaiah’s personal animosity, Micaiah told how the heavenly court had worked out the destruction of Ahab (22:17‑23).44

c. Zedekiah, the false prophet, angered by this clear revelation of false prophecy, struck Micaiah on the cheek, and stated dramatically that the spirit of Yahweh belonged to him not Micaiah. What audacity! Micaiah was remanded to prison with the Parthian shot that if the king returned in peace, Yahweh had not spoken to him. This was an oblique way of saying, when Ahab dies everyone will know that Yahweh has spoken by me (22:24‑28).

4. The battle was lost, and Ahab was killed (22:29‑40).

a. Ahab in his foolishness tried to disguise himself so as to avoid the prophecy of Micaiah. He was shot “inadvertently” by a bowman shooting randomly. The death of the king enervated the army, and they called a retreat. When his chariot was washed out in Samaria the dogs licked his blood as Elijah had predicted (22:29‑38).

b. The succession statement is made including a brief recapitulation of Ahab’s building projects in Samaria along with the ivory house. Samaria has been excavated and the palace of Ahab was unearthed. Ahaziah succeeded his father (22:39‑40).

G. Jehoshaphat ruled in Judah as a good king (22:41‑50).

Jehoshaphat was a good king although he came in for more severe criticism in the book of Chronicles. He was noted for following his father Asa’s good example in spite of the fact that the high places were not removed. It is stated without criticism that he made peace with the king of Israel. His spiritual character was evident in his removal of the sacred male prostitutes from the land. Edom had a deputy, and Jehoshaphat carried on shipping from Ezion-Geber as Solomon had done. He refused to join with Ahaziah in a shipping alliance.

H. Ahaziah ruled in Israel as a wicked king (22:51‑53).

Ahaziah’s reputation was no different from his father’s. He worshipped Baal and otherwise did evil as his father and mother had done.

1See my God Rules among Men for an integrated harmony of Samuel, Kings and Chronicles.

2But see Bähr in Lange’s Commentary. He argues that it is strictly medicinal and quotes Galen.

3The evident co-regency of David and Solomon in Chronicles indicates that David must have improved.

4See 2 Sam 3:2‑5; Chiliab (called Daniel in 1 Chron 3:1) does not figure at all in the history: did he die?

5The succession narrative comprising most of Second Samuel is continued into Kings. One more son of David must be declared ineligible so that God’s choice, Solomon, might rule in peace and with success. Saul’s descendants have been dispatched, Amnon and Absalom are dead; Adonijah is put out of commission, but as long as he lived, he was a threat. Consequently, he will be killed in the succeeding chapters along with Joab the most potent anti‑Solomon personage of all. Abiathar (descendant of Eli) will be “put out to pasture” to render him ineffective.

6Cf. Jer 41:17 where Chimcham (Barzillai’s son?) seems to have a piece of property as a “fiefdom.”

7So, we must understand Abner and Rizpah and Absalom and David’s concubines, cf. also Reuben and Jacob’s concubine.

8Jeremiah, a priest, also lived in this village.

9For a discussion on high places, see my Samuel notes, p. 174.

10The temple was not finished, and the tabernacle was at Gibeon according to the parallel account in Chronicles.

11See DeVries, 1 Kings, loc. cit., for a discussion of the various offices.

12This should be understood in the sense of garrisons such as David had already stationed in Damascus. This is indirect control not direct and should not be considered a fulfillment of the Abrahamic covenant.

13Cf. Ecclesiastes 2.

14See Zvi Gal, “Cabul a Royal Gift Found,” BAR 19 Mar/Apr (1993) 38-44, 84. Gal excavated a site he believes is Galilean Cabul.

15See G. J. Wightman (“The Myth of Solomon,” BASOR 227/28[1990] 5-22) who argues that these gates must be dated later. He does not deny a flourishing period under Solomon, only the archaeological dating. See Dever’s response in the same issue, “Of Myths and Methods,” pp. 121-30.

16See Avigad, Discovering Jerusalem.

17Alan Millard, “Does the Bible Exaggerate King Solomon’s Golden Wealth?” BAR 15 (1989): 20-34.

18Albright (Yahweh and the Gods of Canaan, p. 236) says that Moloch is a term for human sacrifice and not a deity. The word Topheth, he says, refers to cremation pits for child sacrifice. However, more recent scholarship is swinging back to the biblical position that Moloch is really a deity. See works on the Phoenicians for more information on Topheth and child sacrifice.

19See Thiele, Mysterious Numbers of the Hebrew Kings.

20Shechem was an ancient religious center for the northern tribes in Ephraim. Jeroboam was from Ephraim. It would appear that Rehoboam was being forced to come to northern territory to defend himself, cf. Judg. 9:1‑2.

21See A. Mazar, “Bronze Bull Found in Israelite ‘High Place’ from the Time of the Judges,” BAR 9 [1983] 34-40.

22See 2 Chron 11:13-17 where Levites and priests from all the tribes moved to Judah. See also Magen Broshi and Israel Finkelstein, “The Population of Palestine in Iron Age II,” BASOR 287 (1992): 47-60.

23Who was this old prophet, and why did he lie to the prophet from Judah? He certainly seems to be a prophet of Yahweh because of his constant allusions to him. The only thing I can conclude is that he was so desirous of associating with this man that he lied to get him to come to his home. Was the old prophet compromised to the point that he was ineffective as a prophet and yet sensitive enough to want to be identified with the truth? It may seem unfair that Yahweh would kill the Judean prophet since the old prophet professed to be speaking from Yahweh, but God expects his prophets to obey him, and his orders were quite explicit and clear on the issue. Those who are closest to the Lord are expected to obey him best.

24Take note of Gehazi, Elisha’s servant (2 Kings 5), and Ahab (1 Kings 22) who dis-guised himself in battle.

25For a list of cities Shishak claims to have conquered, see ANET, pp. 242-243. A fragment of a monumental stela was found at Megiddo which may indicate that he really conquered that city.

26Kings uses Abijam which means my father is the sea. This sounds much like the Ugarit material where jam or yam means “the sea.” The Chronicler uses a more orthodox name, Abijah, “my father is Yahweh.”

27See God’s rebuke through Hanani in 2 Chron 16:7‑9.

28Note: Assyria will hereafter refer to Israel as Bit Omri, i.e., the dynasty and land of Omri.

29Jezebel may mean “without cohabitation” indicating her connection with the fertility cult. Ethbaal means “man of Baal.”

30The Bible does not speak much of the Assyrians at this time, but they were beginning to make themselves felt. Contact came in the ninth century when a coalition of kings (Arameans and others) which Ahab joined fought Assyria. This coalition was an effort to assert independence in the west from the Assyrian over lordship. The account of this battle is found in Shalmaneser III’s annals and is dated at 853 B.C. The Assyrians claimed victory, but they did not return for some time, and it took several battles before they were completely triumphant. This happened in 841 B.C. and Jehu, king of Israel, and other kings were forced to come to Nahr el-Kelb to pay tribute. This event was recorded on Shalmaneser’s black obelisk (CAH, 3:13‑14).

31See DeVries, 1 Kings, for a discussion of the paganism involved.

32Only the 450 prophets of Baal are referred to later. Perhaps the Asherah prophets decided not to come.

33Furthermore, the Hebrew words, “to see” and “to fear” in this construction, without vowels, look exactly alike. I would opt for the first meaning, “When he saw . . .” [as in the MT]. Even if the translation should be “and he was afraid,” fear was not the only reason for fleeing.

34Is this the cleft of the rock in which Yahweh hid Moses when he passed by (Exod. 33:22)? The Hebrew says “The” cave.

35Is this representative of what happened when Yahweh revealed himself to Israel?

36Son of the storm god Hadad. See ANET p. 655 for a brief inscription of this king from the time of Ahab.

37An Aramaic inscription written by a certain Zakir comes from the eighth century and is a generation later than the context of 1 Kings 20. It represents the petty-state wars in this era.

A stela set up by Zakir, king of Hamat and Lu’ath, for Ilu-Wer, [his god].

I am Zakir, king of Hamat and Lu’ath. A humble man I am. Be’elshamayn [helped me] and stood by me. Be’elshamayn made me king over Hatarikka [Hadrach—see Zech. 9:1].

Barhadad, [Aramaic has Bar for the Hebrew Ben] the son of Hazael, king of Aram, united [seven of] a group of ten kings against me: Barhadad and his army; Bargush and his army; the king of Cilicia and his army; the king of ‘Umq and his army; the king of Gurgum and his army; the king of Sam’al and his army; the king of Milidh and his army. [All these kings whom Barhadad united against me] were seven kings and their armies. All these kings laid siege to Hatarikka. They made a wall higher than the wall of Hatarikka. They made a moat deeper than its moat. But I lifted up my hand to Be’elshamayn, and Be’elshamayn heard me. Be’elshamayn [spoke] to me through seers and through diviners. Be’elshamayn [said to me]: Do not fear, for I made you king, and I shall stand by you and deliver you from all [these kings who] set up a siege against you. [Be’elshamayn] said to me: [I shall destroy] all these kings who set up [a siege against you and made this moat] and this wall which . . . .

[. . . charioteer and horseman [. . .] its king in its midst [. . .]. I [enlarged] Hatarikka and added [to it] the entire district of [. . .] and I made him ki[ng . . .] all these strongholds everywhere within the bor[ders].

I build houses for the gods everywhere in my country. I built [. . .] and Apish [. . .] and the house of [. . .

I set up this stele before Ilu-Wer, and I wrote upon it my achievements [. . .]. Whoever shall remove (this record of) the achievements of Zakir, king of Hamat and Lu’ath, from this stele and whoever shall remove this stele from before Ilu-Wer and banish it from its [place] or whoever shall stretch forth his hand [to . . .], [may] Be’elshamayn and I[lu‑Wer and . . .] and Shamash and Sahr [and . . .] and the Gods of Heaven [and the Gods] of Earth and Be’el‑ ‘[. . . deprive him of h]ead and [. . . and] his root and [. . ., and may] the name of Zakir and the name of [his house endure forever]! ANET pp. 655, 56.

38Hezekiah paid similar tribute to Sennacherib when he capitulated but did not sur-render. Sennacherib adds to the tribute paid: “daughters and women of the palace.” ANET, p. 288.

39So J. A. Montgomery, The Books of Kings, loc. cit. This translation assumes that the word “young men” (ne’arim נְעָרִים) is a military term referring to the officers of the provincial rulers under the king.

40Is this a centralization of power in Damascus?

41See Montgomery, The Books of Kings, loc. cit., for examples of this language else-where.

42ANET, pp. 278‑79.

43Several Hebrew MSS and the Targum have Yahweh, but I suspect the text should stand as it is.

44We have already seen an evil spirit “from Yahweh” coming upon Saul as God’s judgment for his disobedience. This passage in Kings tells us that even false prophecy is under the control of God. (See Josephus, Antiquities, viii, §4-5 for his discussion of this issue.) These false prophets are being used to fulfill the divine purpose of bringing Ahab to his death. The only real question concerns the identity of the spirit in the heavenly court. The ethical question is Does God do evil? Since it is His spirit that caused the lying, God was in some way responsible for the lying. I am not sure that we can satisfactorily solve this dilemma. God is sovereign and controls evil as well as good. Our efforts to explain these situations sometimes result more in casuistic reasoning than solutions. The prophets were false before the spirit came; they were therefore lying before he came. It seems that the spirit in some way used these prophets to lie in the “right” way so as to bring about Ahab’s death.

Related Topics: Introductions, Arguments, Outlines, Teaching the Bible