2. Job

Related MediaSee standard introductions but especially Marvin H. Pope, Job, in the Anchor Bible and LaSor, Hubbard and Bush, Old Testament Survey.

Job and Qoheleth are a response to Wisdom teaching in the ancient middle east. It is good to act wisely, but one should not expect the outcome of one’s acts to turn out as hoped or expected. Job is the ideal person as a man of integrity (תָּם tam). Therefore, his life and example are a response to the common, absolute ideas about wise living.1

I. Date of the book

Since wisdom literature is found in surrounding cultures as early as the second millennium, Pope says that the core of Job could have originated that early. He places the composition in the seventh century. Certainly, the setting of the book is patriarchal.2 The events of the book are surely from the patriarchal period, but the book was probably not put into writing until the heyday of wisdom literature which began with Solomon (1 Kings 4:29‑34) and included Hezekiah (Prov. 25:1).

II. The Text of the Book

The Hebrew of Job is very difficult in places. Not only is it poetry, itself enough of a problem, linguistically it has at least one hundred hapax legomena (words used only one time in the Bible). Attempts to understand these words through cognate languages helps, but not all the problems are solved at this point.

III. The Message of the Book

We have been saying that Samuel/Kings in particular have been based somewhat on the Deuteronomic or Palestinian covenant that taught the Israelites that God blessed those who were obedient to Him and judged those who were disobedient. This concept of retribution theology is certainly correct to a point, but God is not limited to that modus vivendi. He also reserves the right to postpone judgment for sin or blessing for obedience. The failure to comprehend this led to the debate in the book of Job in which both Job and his friends argued from the retributive base alone. Job says God must be unjust for punishing him when he is innocent, and his friends say that God would not be punishing him if he were not guilty. What they both failed to reckon with was God’s sovereign right to allow just people to suffer and unjust people to prosper. The psalmist grapples with this same situation (Ps. 73) as does Jeremiah (12). The disciples of Jesus reflect the same error when they ask their master, “Who did sin, this man, or his parents, that he was born blind?” (John 9:2).

Delitzsch on Job.3

A. The Book of Job shows a man whom God acknowledged as his servant after Job remained true in testing.

1. “The principal thing is not that Job is doubly blessed, but that God acknowledges him as His servant, which He is able to do, after Job in all his afflictions has remained true to God. Therein lies the important truth, that there is a suffering of the righteous which is not a decree of wrath, into which the love of God has been changed, but a dispensation of that love itself.”

B. Not all suffering is presented in Scripture as retributive justice.

2. “That all suffering is a divine retribution, the Mosaic Thora does not teach. Renan calls this doctrine la vieille conception patriarcale. But the patriarchal history, and especially the history of Joseph, gives decided proof against it.”

3. “The history before the time of Israel, and the history of Israel even, exhibit it [suffering that is not retributive] in facts; and the words of the law, as Deut. viii. 16, expressly show that there are sufferings which are the result of God’s love; though the book of Job certainly presents this truth, which otherwise had but a scattered and presageful utterance, in a unique manner, and causes it to come forth before us from a calamitous and terrible conflict, as pure gold from a fierce furnace.”

C. Suffering is for the righteous a means of discipline and purification and for dokimos testing of his righteousness.

4. “(1.) The afflictions of the righteous are a means of discipline and purification . . . (so Elihu) … (2.) The afflictions of the righteous man are means of proving and testing, which, like chastisements, come from the love of God. Their object is not, however, the purging away of sin which may still cling to the righteous man, but, on the contrary, the manifestation and testing of his righteousness.”

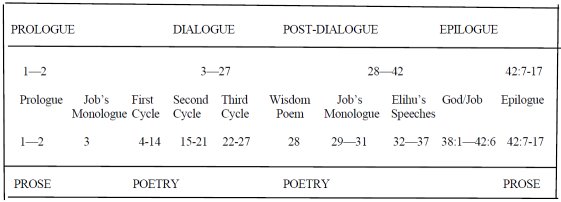

IV. The Structure of the Book

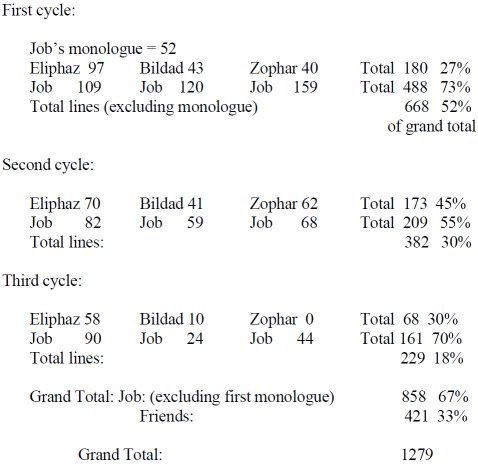

V. Comparisons of lines in the cycles

VI. Outline of Job.

A. The prologue (1:1‑2:13).

1. Job is introduced as a man who worships God (1:1‑5).

Job lived in the land of Uz (an ancient name) and was a righteous man. God’s blessing in his life was evidenced by his physical wealth and large family. He is described as a תָּם tam man. This word means that he was a man of integrity.

There are two areas that have been identified with Uz. The first is around Damascus and linked with the Arameans. The second is Edom and the area of the Edomites.4

2. Job is tested to prove that his faith is not dependent upon his wealth (1:6—2:10).

a. The first test comes in the loss of children and wealth (1:6‑22).

The two great symbols of God’s blessing for faithfulness and righteousness in the OT are wealth (things and children) and health. The book of Job sets out to test the retributive thesis on these two grounds immediately. The first great test comes in the loss of his animal wealth (note the dramatic effect as the story unfolds). Then the word comes that he has lost all his children. Job accepts his fate and refuses to blame God.

The heavenly scene in this chapter is striking indeed. We have a person named the Satan (הַשָּׂטָן haśatan who appears in the heavenly court to accuse Job. The Hebrew word satan as a verb means “to accuse.” Consequently, the noun means “the Accuser.” This scene teaches us a number of things: Satan has access to God in some way; he accuses people to God; God allows Satan certain latitude in dealing with people; and God protects people from Satan. These issues are all peripheral to the story that Job, a good man, suffers unjustly because of Satan’s accusations.5

b. The second test comes in the loss of his health (2:1‑10).

The speech of Job’s wife is interesting. The Hebrew gives her six words, but the Greek adds four verses. The most common attitude about this addition is to assign it to the imagination of the Greek translator or a later editor who, as Davidson says, felt “no doubt, nature and propriety outraged, that a woman should in such circumstances say so little.”6

3. Job’s friends come to “comfort” him (they become the foil in the debate about retributive justice) (2:11‑13).

Eliphaz the Temanite: “Meaning, possibly, ‘God is fine gold.’ According to the genealogies, Eliphaz was the firstborn of Esau and the father of Teman, Gen xxxvi 11,15,42; I Chron 1 36,53”7 Teman is from the Hebrew word yamin or right hand (looking east, the right hand is south). It is associated with Edom (cf. e.g., Jer. 49:7). Bildad the Shuhite: The name Bildad is of uncertain origin. Shuah is the son of Abraham and Keturah. Zophar the Naamathite: the name is found only here, and the location is uncertain. The point of the passage is that these men represent very wise men of the east who are capable of locking horns with Job on this difficult subject of suffering.

B. The Dialogue (3:1—27:23).

1. Job’s monologue (3:1‑26).

a. Job laments that he was ever conceived (3:1‑10).

The whole point of the curse is to say that he should never have been born. It is not so much that he wants to curse his birthday as to say “my life is so bad, it would be better if I had never been born” (cf. Jer. 20:14‑18).

b. Job laments that he did not die at birth (3:11‑19).

If it were necessary for Job to have been born, he should at least have died at birth.8 The Hebrew is nephel tamun (נֵפֶל טָמוּן), lit.: a hidden fall.) Had he died at birth he would have been in Sheol where he would be suffering no pain. (The Hebrew concept of Sheol was vague. It was a place where all went after death [righteous and wicked]). It is rather shadowy and fearful, but better than painful life. Otherwise it is to be avoided. The NT reveals the One who came to “deliver them who through fear of death were all their lifetime subject to bondage” (Heb. 2:15).

c. Job laments that he cannot die (3:20‑26).

Job says, finally, that if he had to be conceived and born, at least he should be allowed to die in the midst of suffering.

2. The dialogue with the three “friends” (First Cycle) (4:1—14:22).

a. Eliphaz’ response to Job’s monologue (4:1—5:27).

He chides Job for being impatient and complaining but acknowledges his piety (4:1‑6).

Eliphaz begins the argument that will be repeated in a dozen different ways throughout the book. Blessing comes on the obedient and suffering on the disobedient, ergo: Job has sinned. Eliphaz begins gently with Job, but when Job stubbornly defends his position, the men get more severe in their statements.

He argues that sin brings judgment (4:7‑11).

All human experience, he says, proves that the innocent do not suffer (if they suffered they were not innocent). This flies in the face of actual experience unless one interpret circumstances to fit the theory (which they apparently did).

He argues (quoting his vision) that man cannot be just before God. This seems to be a statement of frustration: man cannot avoid trouble (4:12‑21).

There is no use calling on even angels to help because man is destined to trouble (5:1‑7).

He argues that there is still hope in God who sets all things right (5:8‑16).

God is the great creator. He is beyond human comprehension, but He still has compassion on the human being. He will judge the wicked and vindicate the just. Therefore, he pleads for Job to repent.

He argues that reproof and correction are part of God’s works, and that man should submit to their inevitability and reap their benefit (5:17‑27).

The implications of this argument are clear enough: Job has sinned and is therefore suffering. If he will accept God’s punishment and repent, he will be restored to a place of blessing.

b. Job responds to Eliphaz’ arguments (6:1—7:21).

Job complains about his painful state (6:1‑7).

He says that his pain ought to be measured and examined so that people would understand what he is going through. God’s unfair punishment has been harsh, and he suffers from it. He would not be complaining if he did not have good reason.

Job cries out for God to finish him off (6:8‑13).

Since God has brought this great pain to Job, he insists that God should finish what He has begun and kill him. For his part, he has not denied the words of the Holy One, therefore, the least God can do is put him out of his misery.

Job complains about the lack of support from his friends (6:14‑23).

He likens them to a wadi (that only occasionally has water). The caravans hurry their steps toward it thinking they will get water only to find it dry. So are Job’s friends. He has never asked them for money or help; now he only asks them for understanding, but they will not give it.

He demands they tell him what they think he has done (6:24‑30).

Job speaks harshly of his friends’ injustice. He says they would cast lots for orphans and barter over a friend. In other words they are completely unjust in dealing with him. He demands that they stop treating him as they have.

He complains again of his state (7:1‑10).

It is not only his own situation of which he speaks: mankind in general suffers like one impressed into harsh labor, like a slave panting for the shade. So is Job: he suffers physically, his days are short, and he expects to go to Sheol.

He complains of God’s constant demands upon him for right living (7:11‑21).

Job says that God has put a constant watch over him like the sea or the sea monster. This watch is not for his good, but to catch him in evil so as to judge him. Job says that God is unrelenting in his demands, and there is no way to escape Him. God will not pardon him, and he expects to die.

c. Bildad gives his first speech (8:1‑22).

He challenges Job to confess and be restored (8:1‑7).

Bildad angrily tells Job that God is not unjust, and therefore whatever has happened is just. However, in the retributive justice argument, this means that Job’s sons must have sinned to deserve death. Job need only seek the forgiveness of the Almighty to be restored to the place of blessing.

He tells Job that the wisdom of the ages teaches that those who forget God are judged. Therefore, Job needs to confess (8:8‑22).

d. Job responds to Bildad’s arguments (9:1—10:22).

He says that God is sovereign and inscrutable (9:1‑12).

Part of Job’s defense is that God cannot be approached by one who wants to present his case. In this unit, he sets forth the idea that no one can enter a court case with God, because God is completely dominant and man is fragile and weak before Him.

He says that God is unfair in his treatment of Job (9:13‑24).

Job’s words reach the point of blasphemy (as his friends later point out). Job is defenseless before Him, He abuses Job with suffering, and even though Job is absolutely innocent, God declares him guilty.

He says that he is not equal to God and therefore cannot defend himself (9:25‑35).

No matter what he might do to cleanse himself, God would push him into the mud and declare him polluted. There is no lawyer to stand between God and Job to give him a fair hearing. If God would remove His punishing rod, Job would not be afraid to confront Him, but God is completely unfair in the way He deals with His creatures.

He says that God does not understand the human state (10:1‑7).

Since God is not human, He cannot possibly understand human suffering. He claims that God knows that he is innocent and yet refuses to deliver him from suffering.

He says God created him but has cast him off (10:8‑17).

Job speaks bitterly of the finite being God has created only to abandon to suffering. Not only so, but God judges him even if he is righteous. Job dare not lift his head lest God hunt him like a lion.

He returns to his lament about death in chapter 3 (10:18‑22).

Job pleads with God to withdraw from him and let him die in peace. If God allowed him to live at the beginning, surely he can give him some peace now.

e. Zophar gives his first speech (11:1‑20).

He charges Job with arrogance in saying he is innocent (11:1‑6).

The rhetoric begins to heat up as Zophar charges Job with scoffing by saying “My teaching is pure, And I am innocent in your eyes.” He wishes God could speak! If He could, He would say that Job had not suffered enough, since God has not held all his iniquity against him.

He argues that God is transcendent (11:7‑12).

Job’s finiteness means that he cannot take on God in this discussion of righteousness. God knows false men, and obviously He knows Job. Man is a fool to try to argue with God.

He argues that Job should confess and then enjoy the forgiveness and blessing of God (11:13‑20).

In a beautiful poem, Zophar tells Job of the great blessing that would ensue on the repentance of this sinner. He must put iniquity far away, but if he does he will find unprecedented blessing.

f. Job responds to Zophar’s arguments (12:1—14:22).

Job chides his friends and says that God is responsible for all things (12:1‑6).

He argues that he is as intelligent as they are. In his past he trusted God and was known as a man of prayer to whom God listened. But now he sees that those who reject God are at ease and those who serve Him are in trouble.

He says that even nature teaches that God is responsible for all things (12:7—13:2).

He then proceeds to list all the things, good and bad, for which God is responsible. God seems to take delight in turning things on their head (“He makes fools out of judges”). Life, says, Job is unfair; he has seen it all and knows that what he says is true.

He demands an audience with God and declares that his friends would be routed if they met God (13:3‑12).

God, says Job, does not need a defender, least of all those who would be dishonest in their dealings with Him. They must stand before God someday, and God will pronounce them guilty for their false charges against Job. Their arguments are completely worthless.

He declares his innocence (13:13‑19).

In spite of all the harsh things Job has said about God, he says that He will trust Him even if He slays him. He believes he would be cleared if he could only argue his case before God.

He challenges God to be fair to him (13:20‑28).

He asks God for two things (stated in reverse form) (1) to remove His hand from him and (2) not to terrify him with fear. If God will do that then Job will be able to speak to Him and defend himself. He demands that God tell him what his sin is and why He is causing Job to suffer so.

He argues that since man is born as a finite creature, God should let him alone (14:1‑6).

Mortal man stands no chance before God. He is weak and limited, yet God judges him. If man is indeed innately sinful and mortal, how can God expect an unclean person to be clean. He therefore pleads with God to avert His face from this weak creature.

He argues that man’s life is hopeless (14:7‑12).

He extends the mortality theme by contrasting man to a tree. The tree can flourish even after it has been cut down, but man dies and that is the end. Job believes in life after death, but that life is not in the normal sense. There will be no return to life on earth as now known.

He prays for God to have mercy on him (14:13‑17).

Since Job is suffering unfairly from the wrath of God, he pleads for God to hide him (as far away as Sheol) to give God’s anger an opportunity to subside. If he dies, he will not live again (in the normal sense on the earth), therefore, he prays for God to let him live until God’s anger is turned back. So that God will remember him after His wrath has subsided, he wants God to set a limit or mark to remind Him that He has hidden Job. The word “change” in 14:14 (ḥaliphathi חֲלִיפָתִי) is the same as the word “sprout” in 14:7 (yaḥaliph יַחֲלִיף). Job is asking God to let him return to earth again in a renewed body.9

He complains that God is almighty and unmerciful (14:18‑22).

Job’s defense has moved from declaring his innocence (which he continues to do) to arguing from the mortality of the human race. Since God created man, He should not hold man’s limitations against him. He should give him a break by recognizing his weakness and not judging him.

3. The dialogue with the three “friends” (Second Cycle) (15:1—21:34).

a. Eliphaz responds the second time to Job’s speech (15:1‑35).

He rebukes Job for his lack of respect for God (15:1‑6).

Job’s blasphemous words have been created by the guilt within him. His own bitterness and rebellion are evidence that he is not innocent. His evil defense makes it even more difficult to get at the matter spiritually.

He rebukes Job for arrogance in assuming he knows more than others, even more than God (15:7‑16).

Eliphaz demands that Job recognize the wisdom of others and to accept their conclusions. Man is indeed mortal as Job has said: why then should he think he could argue with God. God does not even trust his holy angels, why should he declare sinful man innocent?

He details the suffering of the wicked man who rebels against God (15:17‑35).

Eliphaz lays out in great detail the problems that come to a man who arrogates himself against God. He seems to be including Job in that category.

b. Job responds the second time to Eliphaz’ speech (16:1—17:16).

He complains about the lack of sympathy in his three friends (16:1‑5).

A speech dripping with sarcasm is delivered against the three friends. They are “sorry comforters.” They sit in self-righteous comfort and condemn a man who suffers. Their statements are therefore worthless.

He details the suffering he has undergone at the hands of evil-doers and even at God’s own hand (16:6‑17).

As Eliphaz sets out the sufferings of the unrighteous man, Job lays out the unjust sufferings he has endured All this has happened even though there is “no violence in my hands, and my prayer is pure.”

He cries out for vindication before God (16:18—17:2).

Job has been wronged as was Abel. Abel’s blood cried for vengeance, so does Job’s. Only it is God who has committed the crime. Who then can defend Job? He asked for an umpire in 9:33 (mokiaḥ מוֹכִיחַ), a vindicator (redeemer) in 19:25 (goel גֹּאֵל); an interpreter in the passage before us; and an intercessor in an extended passage in 33:23ff. Job is begging for someone to stand between him and a holy righteous God. While Job is accusing God of injustice, he has also pled the cause of mortal man. This thinking, preliminary as it is, underlies the idea of the mediator who was Christ Jesus (1 Tim. 2:5).

He asks for someone to defend him (17:3‑5).

Job wants God to exchange pledges with him so that there will be integrity in their argumentation. He challenges the integrity of the friends by saying that they lack understanding and are really informing against a friend for a share of the spoil. This is a strong charge.

He says he suffers as a righteous man and therefore other right-eous people will be appalled (17:6‑16).

Job argues that people who are righteous and discerning will understand that he is suffering wrongfully. The clear implication is that his friends are not righteous. In spite of his suffering, he will maintain his integrity and ultimately expects to be vindicated (as he indeed was).

c. Bildad responds the second time to Job’s speech (18:1‑21).

He rebukes Job for his outburst against his friends (18:1‑4).

He asks Job why he thinks he should receive special treatment. Will the earth be abandoned for Job’s sake or the rock moved from its place? Who does Job think he is?

He sets forth in elaborate and gruesome detail the fate of the wicked (18:5‑21).

d. Job responds the second time to Bildad’s speech (19:1‑29).

He rebukes his friends again and specifically states that God is the cause of his problems (19:1‑6).

He complains that God will not give him justice (19:7‑12).

No matter where he turns, God is against him. When he cries out for help, God does not answer him. God has treated him as an enemy and has brought his army against Job.

He complains that everyone has turned against him (19:13‑22).

All his family, his wife, his friends and acquaintances have turned away from him. Even his three friends are mistreating him in the same way God is doing.

He cries out for a recording of his justice and gives a strong testimony of faith in God (19:23‑29).

19:25, 26 says: “And as for me, I know that my Redeemer lives, and at the last He will take His stand on the earth.” “Even after my skin is destroyed, yet from my flesh I shall see God.”10

The minimum this means is that Job believes in some kind of a mediator, a goel, and that there will be a time after death in which Job will stand before God. Whether that is from the resurrected body or apart from his human body, he will be there. Consequently, this verse refers at least to life after death.11

e. Zophar responds for the second time to Job (20:1‑29).

He states again the fate of the wicked (20:1‑11).

If indeed, as Job says, the wicked do prosper, it is only for a little while. Sooner or later, everything catches up with them and they lose everything and get what they deserve.

He argues that ill-gotten gain will cause later suffering (20:12‑19).

The man who cheats to get the nice things in life will have to pay the piper before he dies. He will be unable to enjoy the fruits of his dishonesty for “He swallows riches, But will vomit them up.”

He says that having devoured others, the wicked man will himself suffer (20:20‑29).

With rising crescendo Zophar paints a picture of a man full of lust for material things and pursuing the goal of getting everything he wants until he finally falls and receives the judgment of God.

f. Job answers Zophar for the second time (21:1‑34).

He questions why the wicked prosper (21:1‑16).

He continues to argue that wicked men often prosper and that their fate is the same as that of the righteous (the argument seems to have been made that some of his punishment might have come on his children) (21:17‑26).

He says that the friends’ argument offers no comfort because there is no evidence that the righteous fare better than the wicked (21:27‑34).

4. The Dialogue with the three “friends” (Third Cycle) (22:1—27:23).

a. Eliphaz answers Job for the third time (22:1‑30).

He speaks strongly to Job charging him with immoral acts (22:1‑11).

In chapter 4 Eliphaz acknowledges Job’s righteousness, but in this chapter, his anger seems to get away from him and he accuses Job of things that he has not done. Perhaps Job’s stubborn self-vindication leads Eliphaz to believe he must take strong measures to crack his armor, but this seems to be quite extreme.

He denies that God is obscure and argues that He sees all and is involved in all (22:12‑20).

God is most certainly sovereign, as Job has said, but His remoteness in heaven only gives Him a better view of human existence. God gives good things to the wicked (including Job), and when they turn against Him, He takes it away, but that is as it should be.

He appeals to Job to repent (22:21‑30).

As has been done on more than one occasion, Eliphaz pleads with Job to recognize his sinfulness and repent so that he might be restored to the place of blessing and become in turn a blessing to others. Even another sinner will be delivered through Job’s restoration, although this “humble person” may be Job.

b. Job responds for the third time to Eliphaz (23:1—24:25).

He argues that if he could only present his case to this inscrutable God, he would be vindicated (23:1‑7).

Job pathetically cries out for a fair hearing. He is convinced that if he could only find this deus absconditus and present his case before Him, that he would be fully vindicated and delivered from his judge.

He says that God is inscrutable and sovereign, but he still trusts Him and has obeyed Him (23:8‑17).

No matter where he turns, Job cannot seem to find God. It is frustrating that he cannot confront him, but in spite of this, he believes that God knows all about him and will one day vindicate him. This is a marvelous statement of faith in the midst of a situation of despair.

He says that God does not pay attention when many injustices are committed (24:1‑12).

Job lists a series of crimes he knows are committed by wicked people. The poor suffer at their hands dreadfully. The only conclusion at which Job can arrive is that God does not pay attention. If He knows everything, and yet does nothing about this situation, at what other conclusion, asks Job, can one arrive?

He says that many deeds are done in darkness (and implies that God does nothing about them) (24:13‑17).

He speaks of God’s injustice to people (is Sheol being personi-fied?) (24:18‑25).

This is a very strong statement and is really blasphemous. Job charges God with complete injustice toward the poor and innocent. He sustains them long enough to abandon them. Job demands that people prove him a liar if what he has said is not true. Job’s theology can only lead him to this conclusion, for he does not understand that all suffering is not the result of sin nor is all unpunished wickedness forever unpunished.

c. Bildad answers Job for the third time (25:1‑6).

He gives a brief response much like previous ones: God is holy and transcendent while man is utterly insignificant, so why does Job think man has any right to claim standing before God?12 Bildad’s argument in 25:4-7 is parallel to that of Eliphaz in 4:17-19.

d. Job answers Bildad for the third time (26:1‑14).

He rebukes his friends for being no help (26:1‑4).

The strong, almost bitter, statements in the mouths of the three friends have not intimidated Job. He lashes out one more time against the insipid counsel of these men. The book of Job is teaching that the theology of these men is incorrect. Job’s evaluation of it and them is accurate as his vindication at the end proves. But his own theology was not accurate either and needed to be set straight. This was done in God’s speeches.

He speaks of God’s omnipotence and omniscience (26:5‑14).

Job’s final thrust at Bildad is to show again the remoteness and inaccessibility of God. He speaks of His creatorship and control over nature. He uses imagery drawn from Canaanite mythology (here used probably as we use Greek mythology) to show the greatness of God.13 Even though Job has hardly scratched the surface of God’s ability, we have seen enough to know how great He is and yet, says Job, we hear scarcely a word from him.

e. Job answers a final time though no opponent’s speech is given (27:1‑23).

Job stoutly maintains his own righteousness and avers that he will never admit to the correctness of his friends’ accusations (27:1‑6).

He says that God will indeed cut off the wicked (27:7‑12).

This section is strange, not only because Zophar does not speak a third time, but because Job seems to acknowledge what he has been denying.14 Keil and Delitzsch may be right in arguing that Job throws their own argument back at them and says that he does not fit it.15

He then lists the fate of the wicked (27:7‑23).

Has Job shifted arguments? Earlier he was saying that since he was suffering, but had not sinned, God must be unjust. Perhaps he is saying that God does indeed judge the wicked, but since Job is not wicked, he will be vindicated. Delitzsch says that Job holds up the same mirror his friends have been showing him. Job argues that he does not fit the image.

C. Post dialogue (28—42:6).

1. A wisdom poem (28:1‑28).

This poem does not seem to fit well with the argument, and it has no heading. As a result, the critics see it as a beautiful poem, probably composed by the author of the dialogues, but not part of the original Job story. It would be better to see it as an addendum to Job’s speech showing that wisdom, so necessary in understanding God’s dealings with mankind, is very rare and valuable. His friends certainly do not have it, and Job himself could stand a larger portion.16

a. There is a source for all kind of things (28:1‑11).

Job describes some of the mining techniques of ancient times as people searched for Iron ore, gold and other precious stones and metals. Man’s ingenuity has gotten him much material.

b. However, wisdom cannot be found (28:12‑22).

Job refers to all the ancient places from which precious metals and other desirable objects were brought. However, without exception, they say that they do know where wisdom may be found. Not even Abaddon and Death (place of the body after death) can say more than that they have heard of wisdom.

c. God is the sum of wisdom and he tells man that wisdom is to fear the Lord (28:23-28).

God as the great creator and sustainer has the wisdom necessary for such activity. He has also instructed his human creatures that to fear Him is wisdom and to depart from evil is understanding.

2. Job’s monologue and final statement (29:1—31:40).

a. Job speaks of his past glory (29:1‑25).

He was a highly respected man (29:1‑11).

He was respected because of his deeds (29:12‑20).

(1) Orphans (12‑14).

(2) Widows

(3) Weak (15‑16).

(4) Anti wicked (17).

(5) He thought all this would bring God’s blessing (29:18‑20).

He returns to discuss his past glory (29:21‑25).

b. Job speaks of his current misfortunes (30:1‑40).

Insignificant people mock him (30:1‑8).

He is in constant danger from them (30:9‑15).

His physical pain is great (30:16‑23).

He says it is normal to cry out in distress (30:24‑31).

c. Job defends his integrity (31:1‑40).

God knows his conduct (31:1‑4).

He has been honest (31:5‑8).

He has been moral (31:9‑12).

He has been just (31:13‑15).

He has been compassionate (31:16‑23).

He has been free from greed (31:24‑28). True piety.

He has been tolerant (31:29‑37).

He has treated his land well (31:38‑40).

With this last strong statement, supported by a series of oaths, Job makes his last self-defense. He is innocent of any sin. His hands are clean.

3. Elihu’s speeches (32:1—37:24).17

a. Elihu introduces himself to the scene (32:1‑22).

Elihu’s background is given (32:1‑10).

The three friends stop talking. They have been unable to answer Job’s arguments. Furthermore, Job has spoken so strongly (even taking oaths) that they have been compelled to silence. Elihu (He is my God) comes unannounced on the scene. He is the son of Barachel the Buzite of the family of Ram. This person seems (like the other three) to have connections with the relatives of Abraham. He is a member of the bystanders who believes he must respond to the failure of the position of both Job and his friends. Gordis’ remarks are insightful: “In essence, Elihu occupies a middle ground between Job and the Friends. The Friends, as protagonists of the conventional theology, have argued that God is just, and that suffering is therefore the consequence and the sign of sin. Job, from his own experience, has denied both propositions, insisting that since he is suffering without being a sinner, God is unjust. Elihu rejects both the Friends’ argument that suffering is always the result of sin and Job’s contention that God is unjust. He offers a new and significant insight which bears all the earmarks of being the product of the poet’s experience during a lifetime: suffering sometimes comes even to upright men as a discipline, as a warning to prevent them from slipping into sin. For there are some weaknesses to which decent, respectable men are particularly prone, notably the sins of complacency and pride” (32:1‑5).18

Elihu is angry because Job has justified himself before God, and the friends are unable to refute him. Therefore, he decides to speak up, arguing that wisdom is not necessarily with the aged and so his youth is not a hindrance (32:6‑10).

Elihu says he has listened carefully to all the arguments and no one has refuted Job, but he is able to do so (32:11‑14).

Elihu says he is indwelt by the spirit and that he can no longer refrain from speaking (32:15‑22).

b. Elihu says that God disciplines people for their own good (33:1‑33).

He challenges Job to the debate (33:1‑7).

He summarizes Job’s position: he is innocent, and God is unjust (33:8‑12).

He argues that God works in His own ways to keep man on the right path (33:13‑18).

He argues that man is chastened physically to cause him to confess so that God can deliver him from going down to the pit (33:19‑28).

He summarizes his point that God disciplines people for their own good (33:29-33).

c. Elihu argues that God is sovereign in all His acts (34:1‑37).

He criticizes Job for his rebellion against the sovereign God (34:1‑9).

He argues that the sovereign God would not act unrighteously (34:10‑15).

He argues that God’s sovereignty precludes wrong acting (34:16‑20).

He argues that the sovereign God scrutinizes men’s ways and requites them their evil (34:21‑30).

He argues that finite man should bow before God’s sovereignty and confess his sin (34:31‑37).

d. Elihu argues that God does not need men (35:1‑16).

He tells Job that God is not troubled with Job’s unhappiness (35:1‑8).

He says that God’s failure to answer Job’s complaint is God’s prerogative—not Job’s (35:9‑16).

e. Elihu argues that God is just in all His deeds (36:1‑33).

He says he wants to argue further, and he knows what he is talking about (36:1‑4).

He argues that God is mighty but fair—even to the wicked whom He admonishes to repent (36:5‑16).

He admonishes Job not to be too hard on the wicked lest he become condemned (36:17‑23).

He argues that man’s chief end is to exalt the creator God (36:24‑33).

f. Elihu finalizes his argument by appealing to the greatness of God in creation (37:1‑24).

He argues that God’s control of nature (storms, snow, rain, etc.) is for the good of all (37:1‑13).

He challenges Job to match his ability against God’s (37:14‑20).

He argues that God is transcendent but fair (37:21‑24).

Elihu’s approach throughout is to defend the justice of God. The friends of Job were concerned to prove him guilty. Elihu sets out to show that God is righteous and fair. In the process he alludes to God as creator (especially in his last speech, 37:14-20). This paves the way for God’s addresses in chapters 38ff. Elihu’s conclusion also is a link with the wisdom speech in chapter 28. “Therefore, men fear Him; He does not regard any who are wise of heart” (37:24).

4. God and Job (38:1—42:6).

a. God challenges Job with a series of references to nature:

He calls Job into the arena of argument (38:1‑3).

He speaks of the creation of the earth (38:4‑7).

He speaks of the creation of the sea (38:5‑11).

He speaks of the day (38:12‑15).

He speaks of the hidden recesses (38:16‑18).

He speaks of light and darkness (38:19‑24).

He speaks of wadis, rain, seed and frost (38:25‑30).

He speaks of the heavenly hosts (38:31‑33).

He speaks of clouds, rain and lightning (38:34‑38).

He speaks of the provision for wildlife (38:39—39:4).

He speaks of the wild donkey and ox (39:5‑12).

He speaks of the ostrich (39:13‑18).

He speaks of the horse (39:19‑25).

He speaks of the hawk (39:26‑30.)

b. God elicits a response from Job (40:1‑5).

He calls Job a faultfinder (40:1).

Job responds contritely (40:2‑5).

c. God takes up His argument again (40:6—41:34).

He chides Job for complaining against Him (40:6‑9).

He challenges Job to be able to control mankind as He does (40:10‑14) (then he can declare himself just).

He challenges him to examine an outstanding example of His creatorship—Behemoth (40:15‑24). Hebrew: behemoth בְּהֵמוֹת a feminine plural noun probably used to denote a very large animal. This may be the hippopotamus.

He challenges him to examine a second outstanding example of His creatorship—Leviathan (41:1‑34). Hebrew: livyathan לִוְיָתָן. This may refer to the crocodile or it may be one of those mythological allusions discussed early in the lectures. Whatever it represents, the message is that God controls it, and Job cannot.

5. Job confesses that he has been wrong in his evaluation of the situation (42:1‑6).

a. He confesses to the greatness of God (42:1‑2).

b. He confesses to his own ignorance (42:3).

c. He admits to willingness to be instructed (42:4).

d. He acknowledges that God has revealed Himself to him (42:5).

e. He repents in sackcloth and ashes (42:6).

D. The Epilogue (42:7‑17).

1. God charges Job’s friends with error and requires sacrifice from them (42:7‑9).

2. God restores Job’s fortunes (42:10‑17).

a. His relatives come back to him (42:10‑11).

b. His animal wealth is restored twofold (42:12).

c. His children are replaced (42:13‑15).

d. Job lived a patriarchal age and died (42:16-17).

As we go through the wisdom literature, we will compare Job with Qoheleth (Ecclesiastes) and Proverbs. Proverbs presents the classic statement that, generally speaking, obedience will be rewarded with blessing and disobedience with cursing. This thesis may underlie some of the presentation in Samuel—Kings. Job is a challenge to that thesis. Indeed, it is normally true, but there are many exceptions. Theodicy is a difficult topic (always has been). Job does not give the last word, because it probably cannot be given. We must trust the sovereign God to do what is right even though experientially we do not always see what we think would be right. Qoheleth argues that in light of that fact, we must enjoy life, do the best we can, expect to see contradictions, and trust God for the outcome.

Excursus on Job: The idea of an intercessor

See, first, Job’s view of death (ch. 3; ch. 14).

1. The umpire (mokiaḥ מוֹכִיחַ)

Job complains in 9:32-33 that God is not a man like him so that he could respond to God and take him into court (mišpat מִשְׁפָּט). “For He is not a man as I am that I may answer Him, that we may go to court together. There is no umpire between us, Who may lay his hand upon us both.” Therefore, Job wishes for an intercessor who could place his hand on both God and Job. The verb yakaḥ יָכַח means “to decide, judge,” “convince,” “convict, “correct,” “rebuke,” “vindicate.” The participle (mokiaḥ מוֹכִיחַ) appears also at 32:11 (none to answer Job’s words) and 40:1 (God says “let him who reproves God answer”).

Dhorme: links it with 5:17; 16:21 for an arbiter. In 9:33, it is the one who decides what is right between two parties.

Hartley: Eliphaz argues in 5:1 that if Job hopes for an angel to intercede for him, his hope is vain. Job in 9:33 senses his alienation from God and desperately longs for a mediator to settle the dispute, but it is not forthcoming.

Gordis: This is the first of three passages revealing Job’s attitude toward God. (16,19 the others.) The second (16:19) he sees God as his witness; the third (19:25) he beholds Him as vindicator and redeemer.

2. The witness (‘ed עֵד)

Laban and Jacob entered a covenant and a cairn became a witness between them (Gen 31:45-52). Jacob called it in Hebrew gal‘ed גַּלְעֵד, Laban called it śahadutha שָׂהֲדֻתָא (31:47). The purpose of this “witness” was to call into account before God the wrong actions of the participants.

In Exodus 19:20 it is used in the sense of warning, but in 20:15 it is the com-mandment prohibiting false testimony against one’s neighbor. In Exodus 25:16 (and many other places) the ark is a testimony (ha‘edath הָעֵדָת) of Yahweh’s covenant with his people. The witness for the “prosecution” is found in Leviticus 5:1.

The word witness is found in Job three times (10:17; 16:8; 16:19). (1) You renew your witness against me (said of God). (2) His body testifies against him: that he has sinned, even though he has not. (3) Job demands that his blood not be covered (Cain/Abel), but he affirms that he has a witness in heaven on high (both ‘ed עֵד and sahadi שָׂהֲדִי appear as in Gen. 31). Job 16:18-21: “O earth, do not cover my blood, and let there be no resting place for my cry. Even now, behold, my witness is in heaven and my advocate is on high. My friends are my scoffers; My eye weeps to God. O that a man might plead with God as a man with his neighbor!”

Gordis and Hartley argue that this can only refer to God. Even though He is just, he is also merciful and loving. Job appeals to this aspect of God.

Dhorme: Job cries for an unrealizable thing: that God might intercede between Himself and mankind. Gordis agrees. Hartley: Essentially agrees. The witness can only be God. Job wants God to witness against himself, because he knows that God is just in spite of what He has been doing to Job.

3. The Redeemer (go’el גּאֵל)

Job 19:26-27 is the most discussed passage in the book. “Oh that my words were written! Oh, that they were inscribed in a book! That with an iron stylus and lead they were engraved in the rock forever! And as for me, I know that my Redeemer lives, and at the last He will take His stand on the earth. Even after my skin is destroyed, yet from my flesh I shall see God; Whom I myself shall behold, and whom my eyes shall see and not another. My heart faints within me.”

Dhorme: God Himself is the goel. So Gordis. Hartley: Goel is often used of Yahweh; Isa. 41:14; 44:24; 49:7-9, 26. The Goel is not the arbiter for which Job wished (a futile hope), but is an expression of confidence in a living God who will intercede for him. Job’s hope is that he will be vindicated before he dies. The following are a distillation of Hartley’s discussion (NICOT).

a. Discusses various meanings of Goel—Avenger of blood, redeemer of property, vindicator of family, God as the redeemer of Israel from Egypt (thus in Isaiah as second exodus).

b. Goel does not refer to a mediator (angelic or otherwise), but to God Himself (cf. Gordis’ discussion of God as prosecutor and defense). (So Gordis; Ringgreen [TDOT] says it cannot be God unless the logic is very loose.) Since Goel refers to God so often, the author would have chosen a different word if he did not mean God. In Job 9, it is an unrealistic wish. Here it is real.

c. God will vindicate him, but when? Not while he is in Sheol, for the dead do not know what is going on (14:21)

d. God will vindicate him when he raises his body—not because that would be the climax of the book, and the resurrection is not mentioned again in the book. (As Job's ash heap.)

e. Conclusion: Job has confidence that God will vindicate him (stand on the dust) while he is still alive and restore him to his former position (as he does). (“End” refers to the time in Job’s life when God will vindicate him.) What about “from my (suffering) flesh”?

4. The angelic mediator (melits מֵלִיץ)

Job 33:23-34. cf. the idea of metatron in later Judaism (Jewish Encyclopedia).

“If there is an angel as mediator for him, one out of a thousand, to remind a man what is right for him, then let him be gracious to him, and say, deliver him from going down to the pit, I have found a ransom.” Who is the angel? Some say the Angel of Yahweh, some say a human friend, some say a conscience. What is the ransom? No answer is given, only God knows. But it is accepted by the mediating angel and the death angel is forced to relinquish his victim.

1See further p. 9.

2See Pope’s discussion (M. Pope, Job in Anchor Bible, New York: Doubleday, 1965), as well as any standard introduction. See also M. Dahood, Psalms in Anchor Bible, New York: Doubleday, 1965, 1:xxxv. The divine, covenantal name Yahweh is used only in chapters 1-2 and 42 (the one use in poetry is questionable textually). Patriarchal names, El, Elohim, Eloah, El Shaddai, are used in the poetry.

3F. Delitzsch, Biblical Commentary on the Book of Job, pp. 1‑4.

4See Pope, Job, for a good discussion.

5See all the commentaries for discussion of the message of Job, but see especially Pope in Job.

6A. B. Davidson, A Commentary on the Book of Job (1-14), 1862, (quoted in Gray, The Book of Job, Pt. I, 25).

7Pope, Job, p. 23.

8This is one of the few references to “miscarriage” in the Old Testament.

9See, Hartley, The Book of Job, NICOT, pp. 236-237, for a good discussion.

10B. C., “Whence a word, ‘skin of my teeth,’” BAR, 2020 (46:3), p. 59, who argues that Job’s teeth are falling out.

11See Dahood, Psalms II in Anchor Bible, p. 196 who repoints “from my flesh” to mean “refleshed by him” and believes that this refers to a new body.

12P. Skehan, Studies in Israelite Poetry and Wisdom, p. 112, says “Bildad’s speech is short because Job cuts him off and answers for him.”

13We might say, God controls the waters that flow through the pillars of Hercules without claiming to believe in that mythological person.

14Because of this, critics reconstruct the passage and put these words into the mouth of Zophar, see, e.g., Pope, Job.

15Dillard and Longman say, “Note that at the end of the third cycle Bildad's speech seems truncated: Zophar lacks a speech, and Job says things that simply contradict everything else he says (27:13-23). The third cycle probably suffers from an error in textual transmission (see extended discussion in Zerafa) in that Job's words in 27:13-23 are either a part of the Bildad speech or the missing Zophar speech. Even with this minor textual correction, however, the short speeches of the third cycle complete the process that was begun in the second—that is, a rapid shortening of the speeches. In this way, the dialogue communicates that the three friends ran out of arguments against Job. This literary device leads nicely to the speech of the frustrated Elihu (chaps. 32-37).” An Introduction to the Old Testament, p. 203.

16Skehan, Ibid., p. 79, says, “There seems no adequate reason to deny this poem to the original author of Job; it draws from the dialogue the only general conclusion that can be drawn from it and balances very well Job’s bitter outcry of chapter 3. This would be the only place in the poetry where the author speaks his own name (at least in 28:28).”

Related Topics: Introductions, Arguments, Outlines, Teaching the Bible