17. Israel/Judah And Egypt 1000 B.C. To 500 B.C.

Related MediaThe Twenty-first Dynasty

(“Post-Imperial” Epoch)1

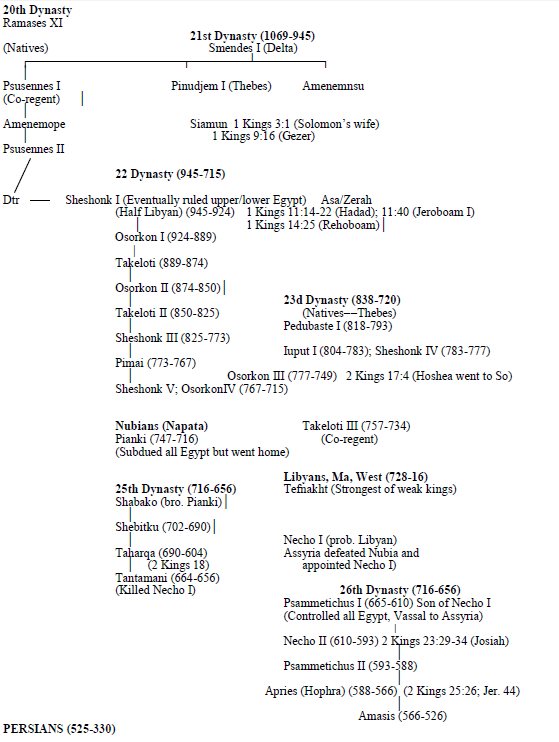

Smendes I (c. 1069-1043) (Saul: 1051-1011)

He was the powerful ruler of the north under Ramases XI. When the latter died without heirs, he became the pharaoh.

Pinudjem I (c. 1053-1010)

He became co-regent in Thebes during the final decade of Smendes I’s life. The reasons are not clear. When Smendes died Pinudjem was old and Nefferkare Amenemnsu became king in Tanis (1043-1039).

Amenemnsu’s half-brother, Psusennes I, also a son of Smendes, became king (1039-991 B.C.) while Pinudjem I was still alive. He was in the prime of life and very active. (David: 1011-970)

Amenemope (993-984 B.C.),

Psusennes I’s son was probably co-regent till his father’s death. Smendes II became high priest and king in Thebes but died soon and was succeeded by his brother, Pinudjem II. He ruled barely a decade leaving few traces. He ruled in Tanis as Pharaoh and high priest of Amun. In Thebes he was undisputed.

Osochor (984-978)

Brief reign (six years). Virtually nothing known.

Siamun (c. 978-959 B.C.). [David, Hadad of Edom 1 Kings 11:14-22, Kitchen, Third Intermediate Kingdom, 274-75]

He was the most active and best attested king of this dynasty rivaling Psusennes I (1 Kings 9:16). Some pharaoh had destroyed Gezer and given it to Solomon as a dowry along with his daughter. If it were early (as it probably was) in Solomon’s reign, the Pharaoh would have been Siamun. The attack on Gezer was probably commercial rather than political. He became an ally of Solomon rather than an enemy. Siamun had crushed a commercial rival; Solomon had direct access to Egypt and had put down the Philistine enemies. Never in Old/Middle Kingdom would a daughter have been given to a foreigner.2

Bible: “…it is known that not long after this time the breeding of horses was actually carried on in a large scale in Egypt and horses were among the most valued possessions of the Delta-princes. Also the strength of Egypt was in her chariots and horsemen (1 Kings 10:28; 2 Kings 18:24).”3 Solomon derived much of his power by controlling the trade-routes from Egypt to Babylonia and from the Red Sea to Syria.

The Philistines may have gone to Egypt for help which would have been honored by David and Solomon. Gezer was chastised by Pharaoh and given later to Solomon. Gaza likewise may have been given by Egypt.4 Solomon was also married to Pharaoh’s daughter (1 Kings 9:16).

Psusennes II (c. 959-945).

His identity is uncertain. He may have been a son or high priest (but even so he was a descendent of Psusennes I). Little is recorded about him. Midway between Tanis and Memphis was the city of Bubastis where a line of Libyan chiefs had by this time been settled for six generations and so reached back to Ramasside period.5 Ramases III settled his captives there.

Twenty-second Dynasty

The Era of Power (945-715) Libya

[Rehoboam to Asa in Judah; Jeroboam to Omri in Israel]

Sheshonk (Shishak) I (c. 945-924 B.C.).

Details for this period are skimpy. “At his death, Psusennes II left no male heir; some time either before or after his death, his daughter Maatkare B was married to the young Osorkon, son of Sheshonk B, the leading man in the kingdom.”

“It was this man who now ascended the throne as Sheshonk I. The new ruler was no brazen usurper or mere parvenu especially if the marriage of Maatkare had preceded Psusennes’ death.”6

Sheshonk, the founder of the 22nd dynasty, was half Libyan, half royal prince of Bubastis on the Delta. Under Merenptah and Ramases III there was a great movement of Libyans into Egypt. Though defeated, many of them stayed. Some were wealthy and gained positions and power. Shishak was from a marriage into the royal house. After about five years, he was able to assert authority over the Theban priesthood and claim upper and lower Egypt.

Hadad II (Edom) and Jeroboam I both fled to Egypt. Sheshonk probably feared to attack Solomon, but with the split of the kingdom (possibly in collusion with Jeroboam I) he was able to defeat Rehoboam in 930 (1 Kings 14:25-28). This event was recorded at Karnak.7

Osorkon I (924-889) was Sheshonk’s son.

Hall believes that Hebrew Zerah, the Ethiopian (2 Chron. 14:9-15), is a corruption of Osorkon who was defeated by Asa in 895,8 but Kitchen says that they are not to be identified. Osorkon is a Libyan whereas Zerah is not called a king and is a Nubian.9 Consequently, he believes that Osorkon, now an old man, sent a general of Nubian extraction. There are no notable events recorded in Osorkon’s reign except this one (unrecorded in Egyptian history for obvious reasons). Sheshonk II ruled as co-regent only (c. 890).

Takeloti (889-874)

This pharaoh is the least-known king of the entire Libyan epoch. His brothers ruled as priests and probably chose to ignore him.

[Jehoshaphat to Ahaz in Judah; Ahab to Hoshea in Israel]

Osorkon II (co-regent as typical in 22d dynasty) (874-850).

Egyptian policy toward Palestine and Syria is more conciliatory. An alabaster vase with Osorkon’s cartouche partly evident shows that a gift was sent to Ahab. The battle of Qarqar took place in 853. The Assyrians were met by a coalition of kings including Ahab from Israel. The Assyrians also mention “a thousand men of Musri.” The contribution of this small force to the battle was the result of Egyptian support of Byblos. This was portentous of a rising Assyria. Assyria claimed victory but it was twelve years later before Jehu paid tribute (841 B.C.).

Takeloti II (850-825).

As Jehu paid tribute to Shalmaneser III, so the Egyptians sent gifts, showing that they were willing to play along with the efforts to pay off the Assyrians.

Sheshonk III (825-773).

(Dynasty 23 begins here at Thebes). The Thebans had been operating under virtual kings for some time, and in spite of efforts from the north to control them, were able to maintain their independence. At this point, however, a descendent of a Harsiesi who had been a “king” at Thebes became a genuine pharaoh even setting up a capital on the Delta. Pedubaste I (818-793 B.C.) was his name.

Pimai (773-767)

Sheshonk V and Osorkon IV, last of the Bubastites (767-715).

Twenty-third Dynasty

(838-720)

This era is poorly attested. Basically only the names of the kings are known. This is essentially a rival dynasty at Thebes.

Pedubaste I (818-793) was the founder of the twenty-third dynasty. His rule was contemporaneous with Sheshonk III.

Iuput I (c. 804-783) and Sheshonk IV (783-777) are not well known.

Osorkon III (777-749).

Takeloti III (757-734). He was co-ruler till 749.

The Nubian Kingdom of Napata.

The Nubians had long and extensive contact with the Egyptians, the latter removing great wealth to the north. These contacts led to a fair amount of “Egyptianizing,” and bi-lingualism.

A certain Kashta, worshipper of Amun, donned the regalia of a pharaoh and even styled himself, the king of upper and lower Egypt. His penetration was at least to Aswan.

In the eighth year of Takeloti III, Piankhy (Nubian) became the king and extended his influence as far north as Thebes and even laid claim to being the protector and in effect ruler of Thebes.10

Rudamun (734-731). Brother of Takeloti III.

Iuput II (731-720?).

“With the division of powers between two senior pharaohs in the Delta (22nd Dynasty, Tanis-Bubastis; 23rd, Leontopolis) and two lesser pharaohs in Middle Egypt (Heracleopolis, Hermopolis), an ‘Hereditary Prince’ of the senior line in Athribis-with-Heliopolis, a whole series of local chiefs of the Ma in the Delta cities, plus a Princedom of the West covering the west Delta, and Nubia ruling from Thebes southwards, the whole former pharaonic dominion in the Nile Valley lay in fragments by the year 730 B.C. Only two of these were of substance--Nubia and the Princedom of the West--and from their contest, a new Egypt was gradually to be born.”11

Twenty-fourth Dynasty

Nubian Dawn and Libyan Eclipse

(728-716)

[Hezekiah to Zedekiah in Judah]

The western part of the Delta was ruled by a Libyan “Chief of the Ma” named Tefnakht. He was more powerful than the pharaohs on the east Delta and even subdued chiefs south toward Thebes.

The new Nubian king was called Piankhy (747-716). Because of the threat of Tefnakht, in a series of campaigns, Piankhy forced the submission of all of Egypt to his control. He then went back to Napata and never returned to Egypt.

A vacuum was left in the north, since Piankhy did not set up an administration nor seek to rule. Consequently, Tefnakht was the most powerful of the weak monarchs. Osorkon IV of the Twenty-second Dynasty continued as a shadow king contemporary with Tefnakht. He was also the northeastern most king and thus exposed to contacts with Western Asia. Consequently, Kitchen believes the “So” to whom Hoshea sent gifts in an effort to thwart Assyrian control (2 Kings 17:4), is Osorkon IV, the last of the Bubastite kings.12 Isaiah (19:11, 13;30:2,4) denounces the Egyptian kings at Zoan (Tanis--east Delta) as fools. The situation in Egypt certainly deserves the epithet.

Sargon II defeated Samaria in 722 B.C. In 720, the year of the death of Tefnakht and the accession of Bakenranef, his son, in Sais, Sargon crushed a revolt in Syria and subdued Philistia as far as Gaza. The Egyptians sent out help but they were routed.13 Osorkon IV sent him a gift. Thereafter both the Twenty-second and Twenty-third Dynasties fade out.

Bakenranef, son of Tefnakht, of the Twenty-fourth Dynasty, became king, but the brother of Piankhy became pharaoh in Napata and soon ruled all Egypt.

Twenty-Fifth Dynasty

Nubian Rule and Assyrian Impact

(716-656 B.C.)

Shabako (716-702 B.C.)

By his second year, Shabako was in charge of Memphis and soon became the true pharaoh of all Egypt. Sargon sent his army commander to deal with a rebellious Ashdod (Isaiah 20) in 712/11. The rebel, Iamani, had fled to Egypt, but he was turned over to the Assyrians. Thus Shabako was at least neutral toward Assyria.

Shebitku (702-690 B.C.)

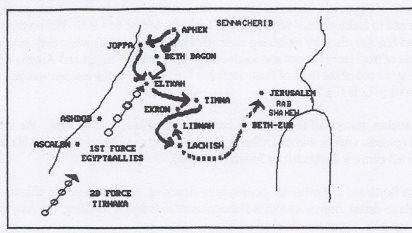

He was the son of Shabako and nephew of Piankhy. He brought his sons to Thebes and to the Delta. Among them was Taharqa who was then twenty years old. In 702/1 Hezekiah and others opened negotiations with the new Nubian king to rebel against Assyria. Sennacherib came west in 701 to put down the rebellion. He defeated the allies, including the first force of Taharqa, at Eltekah, proceeded to demolish the fortified cities of Judah, and sent his officer to demand the surrender of Jerusalem by Hezekiah. However, upon hearing a report that Taharqa was going to attack with his second force, he withdrew Jerusalem to reunite his forces. The Egyptians withdrew, but God miraculously destroyed most of the Assyrian army. Taharqa was not pharaoh at this time, but was referred to as such in 681 when the account was written. Thus it is used proleptically and is not a dual account of Sennacherib’s invasion.14

Taharqa (690-664).

Esarhaddon of Assyria perceived Egypt to be the reason for rebellion among his western provinces. Consequently, he invaded Egypt in 674 but was defeated. He invaded again in 671 and defeated Taharqa. He set out again in 669 to attack Egypt but died on the way.

Under Ashurbanipal the Assyrians ruled Egypt. Taharqa fled to Thebes and then to Napata. The Assyrians appointed Necho I of Sais as a subordinate king (he may have been a Libyan).

Tantamani (664-656).

Tantamani was urged by the Egyptians to return north. He did so and conquered all the territories and killed Necho I. Ashurbanipal sent his army back (663) and again routed the Nubians, driving Tantamani back to Napata. They looted Thebes completely (Nahum refers to the fate of No-Amun or Thebes in 3:8-10. For the text see CAH 3:285). The northern territories continued to be fiefdoms with the Saites and Bubastites permitted by the Nubians some measure of independence.

The Twenty-sixth Dynasty

The Saite Triumph

Psammetichus I (665-610).

This son of Necho I of Sais and an Assyrian vassal was able by 656 B.C. to extend his rule over the entire Delta, Middle Egypt, and finally south to Thebes. Greeks begin to appear in Egypt as warriors and traders. They no doubt assisted Psammetichus in gaining control and formed a colony at Naucratis.

“The union of Egypt as a solid fact gave the king enough confidence to cease paying tribute to Assyria and to form an alliance with Gyges of Lydia by 655 or 654 B.C. However, he may have mollified the Assyrians by remaining their ally (not an opponent) while they struggled with a rising tide of troubles in the east and south-east. The alliance of Egypt and Assyria was certainly in force at the end of the reign of Psammentichus I (610 B.C.) in the momentous years of the fall of Nineveh (612 B.C.).”15

Psammetichus staved off the Scythian invasion that affected all of Asia. He also besieged Ashdod (perhaps while it was controlled by the Scythians) and controlled Gaza. He did not push into the hill country controlled by Josiah (640-609).

With the Scythians and other hill people daily attacking the Assyrians, the efforts of Cyaxares the Mede to defeat Assyria and with Nabopolassar in Babylon rebelling, the Assyrians were in serious trouble. Egypt remained an ally.

Necho II (610-593).

Nineveh fell in 612 and under Ashur-uballit the army regrouped in Haran. Necho went to her side in 609. Josiah tried to stop him and was killed at Megiddo. Necho on his way back to Egypt deposed Jehoahaz and enthroned Jehoiakim. The Egyptians were defeated by crown prince Nebuchadnezzar in 605. In that same year Nabopolassar died and Nebuchadnezzar became king. He forced Jehoiakim to submit to Babylonian rule.

Jeremiah predicted that Nebuchadnezzar would invade Egypt (Jer. 43). Hall refers to the fragmentary inscription “in the 37th year of Nebuchadnezzar King of Babylon [568-67] (the troops) of Egypt to do battle came …(Ama)su, King of Egypt his troops (levied)…Ku of the city of Putu-yawan …a distant land which is in the midst of the sea…many…which were in Egypt…arms, horses, and…he levied for his assistance…before him…to do battle.” He goes on to say Marduk encouraged troops and enemy mercenaries were defeated and fled. He does not believe this gives warrant for assuming that Nebuchadnezzar, now old, would have major battles or enter Egypt personally.16

Psammetichus II (593-588).

Apries (Pharaoh Hophra of the Bible) (588-566).

Apries was essentially in the hands of his Greek mercenaries (much to the resentment of the population). He supported King Zedekiah in his revolt against Babylon and attacked Phoenicia from the sea. The army revolted and put an officer, Amasis (d. 526), in as co-regent. Apries tried to reestablish himself, but was defeated and slain by his own men.

The Persians conquered Egypt in 525 B.C

1This material is based on K. Kitchen, The Third Intermediate Kingdom and H. R. Hall, “The Eclipse of Egypt,” CAH 3:251-269.

2Kitchen, Third Intermediate Period, p. 281.

3CAH 3:256.

4CAH 3:257.

5Kitchen, Third Intermediate Period, p. 285.

6Ibid., p. 286

7CAH 3:258.

8CAH 3:361.

9Kitchen, Third Intermediate Period, p. 309.

10Kitchen, Third Intermediate Period, p. 359. See “Sudan’s Kingdom of Kush,” National Geographic, 178 (1990) 96-125.

11Ibid., p. 361. C. DeVries, “The Bearing of Current Egyptian Studies on the Old Testament,” pp. 33-34.

12Ibid., p. 373-75.

13ANET, p. 285.

14Kitchen ably defends this explanation in The Third Intermediate Period (p. 384-85) and in The Ancient Orient and the Old Testament (pp. 82-83).

15Kitchen, Third Intermediate Period, p. 406.

16See CAH 3:304.

Related Topics: Archaeology, History