14. Ezekiel

Related MediaNotes on the Book of Ezekiel

I. The Prophet Ezekiel.

Ezekiel went in into exile with Jehoiachin in 597 B.C. Like Daniel a few years earlier, Ezekiel was a godly young man who followed the Law of Moses, including the dietary laws. His wife died in exile, and he was prohibited from mourning for her. Some critical scholars have tried to interpret his message in terms of his personality that exhibited such strange behavior. Childs says that this has met with little success.1 Ezekiel was probably twenty‑five years old at the time of the exile (working on the supposition that the thirty years of 1:1 refers to his age). He lived in his own house in exile, at Tel Abib on the Great Canal (3:15). The location, if the river Kebar can be identified with Babylonian naru kabari, was between Babylon and Nippur. He was therefore living in one of the Jewish colonies that the Babylonians had transplanted from Judah.2

II. The Historical Context

Ezekiel’s dated messages began in the fifth year of the exile which would be July 31, 592 B.C. (1:1‑2). The last dated message was the twenty‑seventh year or Apr. 26, 571 B.C. (29:17). Thus Ezekiel’s ministry covered a span of at least twenty‑three years. His message was delivered before and after the destruction of Jerusalem in 586 B.C. He spoke to all Israel, but locally to the exiles whom Jeremiah addressed by letter (e.g., Jer. 29), as people who continued to listen to false prophets and practice idolatry. The contents of Ezekiel indicate that little had changed in the attitude of the Jewish people who had come to Babylon.

III. The Unity of the Book

Early in the twentieth century S. R. Driver could say: “No critical question arises in connexion with the authorship of the book, the whole from beginning to end bearing unmistakably the stamp of a single mind.”3 It was in 1924 that G. Holscher4 began to subject the book to the critic’s knife. Since that time it has undergone radical surgery, particularly by C. C. Torrey, who viewed it as a pseudograph from the third century B.C.; a literary creation without any real historical roots.5 Critical scholarship, in the interest of advancing new theories, often abandons common sense in dealing with these biblical books. The approach of B. S. Childs is refreshing. Though he follows W. Zimmerli in attributing some of the book to a “later school,” he views the bulk of the book as “Ezekielian.”6 His section on Ezekiel can be studied with profit. He argues that Ezekiel was “radically theocentric,” that is, everything was viewed from God’s eternal perspective and is not therefore historically particularistic (he does not direct his invective against historical situations as does an Amos or a Jeremiah). Following Zimmerli, he shows how Ezekiel used the pre‑prophetic Scriptures as the basis for his teaching. Ezekiel’s method was casuistic and priestly in its orientation. Childs’ position is summed up in the statement: “particular features within Ezekiel’s prophetic role which shaped both the form and content of his message contained important elements which the later canonical process found highly compatible to adapt without serious reworking for its own purpose of rendering the tradition into a corpus of sacred writing.”7

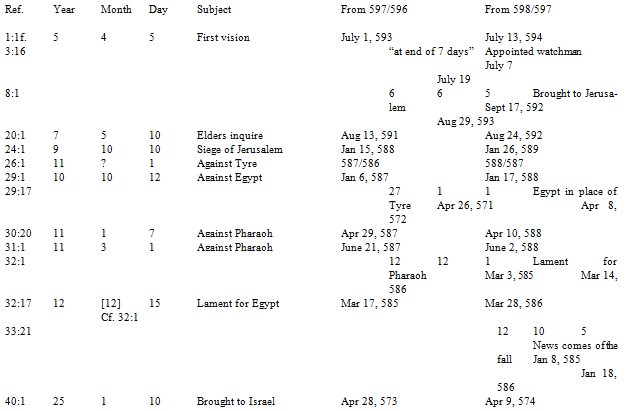

Finegan argues that all the dates in Ezekiel are to be related to the captivity of Jehoiachin. Consequently, he provides the following list:8

“The foregoing may now be seen to constitute a self‑contained and consistent chronological scheme. The only essential difficulty is the problem of whether Jehoiachin’s captivity began in 597 and [or?] 598, and that is a matter of interpretation of the data in Kings and Jeremiah. Reckoning from either year, the notations in Ezekiel fall into a comprehensible pattern. The most significant point at which to check the figures is with reference to the fall of Jerusalem. Here the dates may be tabulated as follows:

|

Nebu began siege (Ezek 24:1) |

Jan 15, 588 or Jan 26, 589 |

|

Jeru fell (Kings/Jer) |

Aug 15‑18, 586 or Aug 26‑30, 587 |

|

Fugitive came with news of |

Jan 8, 585 or Jan 18, 586 |

“The time required for Ezra to journey from Babylon to Jerusalem (Ezra 7:9) was from the first day of the first month to the first of the fifth month, or four full months. The time required here for the fugitive to come from Jerusalem to Ezekiel in Babylonia was from the tenth day of the fifth month to the fifth day of the tenth month, less than five months. The sequence and time of events, compared with the independent data of other Biblical passages, works out with exactitude.”9

Finegan includes the “seven day” phrase in 3:16 as one of the chronological points. Most people would not include it. If it belongs, there are fourteen chronological references, as one might expect. The problem with including it is that it seems to be a sub point under the first main reference in 1:2.

IV. The Structure and Synthesis of the Book of Ezekiel.

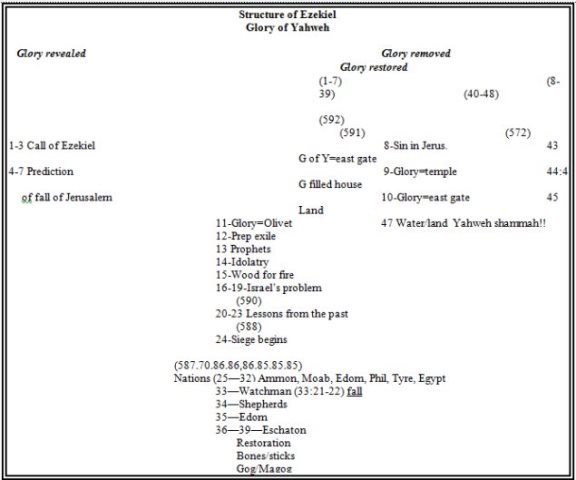

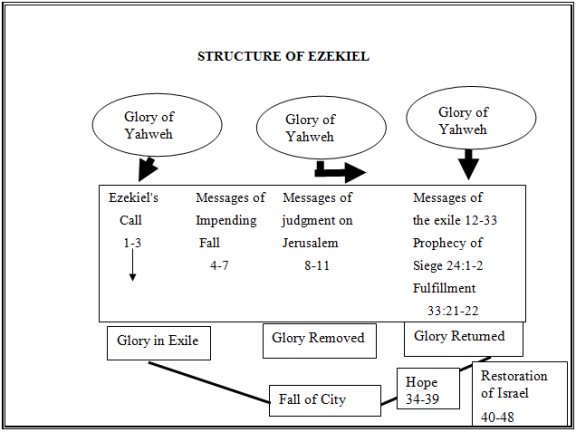

The unifying feature in the book of Ezekiel is the Glory of the Lord. The opening vision during which Ezekiel is called to the prophetic ministry centers on the visible presence of the throne of God. This overwhelming presentation is to show the theocentricity of the book: God is the center of this unfolding drama.

The first vision concludes with the statement, “Such was the appearance of the likeness of the glory of the Lord. And when I saw it, I fell on my face and heard a voice speaking” (1:28). The “call” unit returns to the theme of the glory of the Lord in 3:12 and concludes with reference to the Gory of the Lord (3:23) where we are reminded that it is the same glory of the Lord referred to in chapter 1.

Chapters 4-7 are predictions of the coming siege and fall of Jerusalem. They are to show the necessity of God’s judgment because of the sinfulness of the people. The argument, however, moves back to Jerusalem in 8-11. The exiles kept arguing that God would not destroy the holy city. The same obtuseness with which Jeremiah deals (“the temple of the Lord will prohibit the fall of this city”—ch. 7) is faced by Ezekiel in the exile. This unit shows the continued perverse pagan practices that deserve and will receive the judgment of God. Furthermore, these perverse practices led to the removal of the glory of God (a symbol of the removal of God’s protective blessing). Before the glory is removed, we are allowed to see it (8:4) and are reminded that it is the same glory seen in the exile. The glory begins to move in chapter 9 (v.3) to the threshold of the temple. In chapter 10 there are four steps in the removal: (1) from the cherub to the threshold of the temple (10:4), (2) from the threshold to a place over the cherubim (10:18), (3) accompanying the cherubim, it moves to the east gate of the temple, (4) from the east gate it goes out and stands over the mount of Olives. Thus, God was demonstrating the departure of His blessing and protection of Jerusalem.

Ezekiel’s visit to the pagan city of Jerusalem in a vision (8:1) occurred in 592 or some six years before the fall in 586. Now (40-48) some twenty years later, he revisits the land in a vision. The temple, so tragically destroyed in 586, is being rebuilt in glorious dimensions.

When the temple is completely measured, he sees the glory of the Lord returning from the way it disappeared in chapter 8 (43:3-4).

The argument of the book is complete: Yahweh, because of His justice, had to punish His people for their sins. However, the future is glorious for Israel, and in that future time, they, their land and their temple will be restored. At that time, the return of God’s protective care will take place as the glory of the Lord returns to the temple from which it departed (in a figure) prior to 586.

The event on which the book centers is the fall of Jerusalem. One of the signs to the exiled community of the legitimacy of Ezekiel’s message is that he will become supernaturally mute (3:26). He will be able to speak only in an official capacity, that is, when God gives him a message. All the messages up to 33 bear on the inevitable siege and fall of Jerusalem and the reasons for that end. However, in 24:2, 25-27, God tells Ezekiel that the siege has begun. He is to write the day down so that everyone will know that he has received the information divinely. Further, when the city falls, Ezekiel will be able to speak freely (24:27). When the messenger of the disaster arrives in 33:21, Ezekiel was able to speak without inhibition. All this was a sign to the people.

The messages after the fall, deal with Israel’s future, including the restoration of the two nations (36-37), invasion in the Eschaton of Gog and Magog, and the idyllic restoration of people, land, and temple. “Then they shall know that I am Yahweh.”

V. The Outline of the Book

A. God pronounces judgment on Israel (1:1—24:27).

1. Yahweh calls Ezekiel to a difficult ministry on July 1, 593 B.C. (1:1‑3:27).

a. The vision of the glory of God (1:1‑28).

The time element “thirtieth year” is much debated. It should probably be understood as the age of Ezekiel; the age at which a priest (at least the Levite) began his ministry (Num. 4:3) (1:1‑2).

The four living creatures (hayyoth חַיּוֹת) obviously represent the presence of God. They form the basis for the revelation of God to John as well (Rev. 4:1‑11). Each creature has four faces and four wings. The four faces are like that of a man, a lion, a bull, and an eagle. In Revelation 4:7 each creature has the characteristics of one of the above. They also have six wings (as in Isaiah 6) while Ezekiel’s creatures have four wings. All kind of lights flash back and forth in Ezekiel’s creatures (1:4‑14).

The movement of the living creatures is linked to a series of wheels with a strange configuration (wheel within a wheel). The rims have eyes all around them. The living creatures are linked with the wheels and the spirit of the living creatures is in the wheels (1:15‑21).

An expanse is over the heads of the living creatures under which the creatures move, and the sound of their wings is like the sound of the Almighty. The throne of the almighty is in the expanse. Sitting on it is a figure with the appearance of a man (cf. Daniel’s Ancient of Days). A rainbow surrounds the throne (1:22‑28).

A comparison of Ezekiel 1 with Revelation 4 yields the following results:

|

Ezekiel |

Revelation |

|

|

|

|

Living Creatures (Heb.: hawoth) |

Living Creatures (Gr.: zon) |

|

Four faces: |

Each one like: |

|

Man |

Lion |

|

Lion |

Calf |

|

Bull |

Man |

|

Eagle |

Eagle |

|

Four wings |

Six wings |

|

Eyes on rims |

Full of eyes |

|

One like a man |

One sitting on the throne |

|

Throne, lapis lazuli |

Like a jasper stone |

|

Rainbow in the clouds |

Rainbow around the throne |

|

|

Twenty‑four elders |

|

|

Lightning, thunders |

|

|

|

|

THE GLORY OF THE LORD |

HOLY, HOLY, HOLY |

Without trying to go into details on the significance of the component parts of the vision, suffice it to say that the entire vision is designed to show the glory of God and to overwhelm Ezekiel (the same thing happened to Isaiah). The end of this vision is to convince Ezekiel of the theocentricity of God in the universe. All that happens comes from God. He is the beginning and the end. Ezekiel is the “son of man,” the representative of the human race with all its limitations.

b. The call of Ezekiel to speak to a stubborn people (2:1‑7).

Ezekiel is addressed as the “son of man.” This is not to be equated with the “son of man” in Daniel 7:13 where it is a messianic title. Throughout the book “son of man” is applied to Ezekiel as the representative of the human race before a holy god. When God addresses him, the Spirit enters him and he hears God speaking (2:1‑2).

Ezekiel is told that his task will be difficult. Israel is rebellious, but they will know that Yahweh God has sent a prophet among them. Ezekiel is told not to fear them in spite of the persecution he will receive (cf. Jeremiah’s call) (2:3‑7).

c. The place of Scripture in Ezekiel’s ministry is illustrated by the scroll (2:8—3:11).

An extensive quote from Childs is appropriate here:10

“Surely one of the most important aspects of Ezekiel’s message was its dependence upon the activity of interpretation within the Bible itself. Not only was Ezekiel deeply immersed in the ancient traditions of Israel, but the prophet’s message shows many signs of being influenced by a study of Israel’s sacred writings. The impact of a collection of authoritative writings is strong throughout the book. . . . Thus, for example, in ch. 20 Ezekiel is not only making use of the great traditions of the Egyptian slavery, exodus, and conquest, but he offers a detailed and radical reinterpretation of the law of the first‑born found in Ex. 22:28. Again, the vision of the seventy elders of Israel ‘each with a censer in his hand’ is not understood unless this cultic abuse is seen in the light of the covenant ceremony in Ex. 24.9ff. and the judgment of Korah in Num. 16.16ff. Or again, in the portrayal of Gog and Magog (chs. 38‑39) one can recognize the influence of Isa. 5.26ff.; Jer. 4.29ff.; and Ps. 46.”11

God tells Ezekiel not to rebel as Israel does, but to accept the order to eat the scroll. The scroll was written on the front and back. Its contents were lamentations, mourning and woe. At God’s command he ate the scroll and it was as sweet as honey to his taste12 (2:8-3:3).

The commission is given to Ezekiel. The scroll represents the message of judgment Ezekiel is to preach. The people will be hard and unwilling to listen, but God has made Ezekiel hard as well so as to respond to their resistance. His message will be “Thus says Yahweh” (3:4‑11).

d. The carrying out of the commission begins as the Spirit lifts him up (3:12-27).

He hears a great noise with a shout of “Blessed be the glory of Yahweh in His place.” The Spirit takes him away, and he goes in bitterness of spirit.13 He comes to the exiles in Tel‑abib where he sits in morose silence, meditating on the bitter message for seven days, “causing consternation among them” (3:12‑15).

God expands the commission to tell Ezekiel that he is a watchman. This important section on the responsibility of the watchman and his hearers must be understood in the context. The watchman is Ezekiel warning the people of Israel. The death or life spoken of is to be taken literally. They will die by the sword, pestilence or whatever judgment befalls them. This is a similar message to that of Jeremiah (3:16-21).

Ezekiel is then told by God to begin his ministry. He was taken out to the plain (the Euphrates Valley—habiqe‘ah, 14

2. Ezekiel begins his ministry of prophecy to Israel by symbolically acting out the siege (4:1—5:17).

a. The first symbolic act is the brick (4:1‑3).

Ezekiel is to take a brick, draw a map of Jerusalem on it so that it can be identified, and pretend to lay a siege against it. He will do this by making a siege wall, a ramp, and by placing tents and battering rams around it. All Israel is to understand by this that God is going to use Nebuchadnezzar to besiege Jerusalem and capture it.

b. The second symbolic act is lying on his side (4:4‑8).

Greenberg, works from the dedication of the temple in 970 B.C. This brings him to 580 B.C. as the period of time when Israel was sinning. He cites Lev. 26 for covenant curses applied to continual sins.15 Gardiner suggests that the 430 years in Egypt forms the backdrop (Exod. 12:40‑41). Judah is to be punished forty years (as in the wilderness); Israel three hundred ninety years (430‑40).16 Keil agrees except that he believes the 40 years represents Moses’ sojourn.17 It is then an indefinite prediction of judgment. Ezekiel must have lain on his side parts of each day. Using Finegan’s data there are approximately 445 days between vision one and two (1:1 with 8:1).

c. The third symbolic act is eating rationed food (4:9‑17).

The lack of food is illustrated by taking certain staples, making bread from them and eating them for the three hundred and ninety days. He is to take scales so as to ration the food to twenty shekels per day. The water is likewise to be limited, and barley cakes are to be baked over human excrement. This latter will symbolize that the Jews will eat unclean food in captivity. When Ezekiel protests the non‑kosher cooking fuel, God allows him to use cow’s dung. The first illustration is to represent the fact that food will be limited during the siege.18

d. The fourth symbolic act is the cutting of hair (5:1‑12).

The conclusion of the siege is illustrated by what Ezekiel does with his hair. Ezekiel is to shave his head and face with a sharp sword. The hair will then be divided into three parts.

One part he burns in fire.

One part he cuts with the sword.

One part he scatters to the wind, waving a sword.

A few he puts in the edges of his clothes.

Some he throws in the fire.

The reason for this judgment, God says, is that he selected them to be in the center of the nations. However, Israel rebelled and rejected God’s ordinances and statutes. They are worse than the nations around them, therefore, God is judging them. The siege will be terrible (fathers eating sons, etc.) and many will be scattered. God will not spare them because they have practiced idolatry in His sanctuary (5:5‑12).

e. The result will be the satisfaction of God’s anger (5:13‑17).

God’s just anger against an ungrateful and rebellious people will be appeased (propitiated). The judgment will be awful, but it will serve as a warning to both the people of God and those who are around them. This is the first full statement of the exile.

3. God gives a series of woe declarations against the people of Judah (6:1—7:27).

a. O Mountains of Israel (6:1‑10).

The mountains of Israel stand for the nation of Israel (included are the hills, ravines and valleys). God decrees that He is going to bring judgment against Israel. The emphasis is placed on the idolatry (high places, altars, incense altars, idols). God will kill His people and let their corpses lie around their altars. Then they shall acknowledge that He is Yahweh (this is an important phrase, appearing about 72 times (6:1‑7).

A remnant will be left in spite of this devastating judgment coming upon God’s people. These will be in the captivity where they will remember Yahweh and the pain their adulterous hearts have caused Him. Then they will know that Yahweh is their God. When that happens it will be clear that His chastisement has not been futile. Then they shall acknowledge that He is Yahweh (6:8‑10).

b. Alas because of the evil abominations (6:11‑14).

The three‑fold judgment of God is promised against Judah: plague, sword, and famine. God pronounces the litany of idolatry seen many times in Isaiah and especially in Jeremiah. Death is promised and the devastation of the land are promised. Then they shall acknowledge that He is Yahweh.

c. An end! An end is coming on the four corners of the land (7:1-4).

God promises that He will bring judgment on the land of Judah because of their idolatrous practices. Then they will acknowledge that He is Yahweh.

d. A disaster, a unique disaster is coming! (7:5‑9).

This warning is parallel with the preceding. An end is coming on the land. God’s wrath will be poured out on them. They will suffer the results of their idolatrous practices. He will show no pity (as in 7:4). Then they will acknowledge that He is Yahweh.

e. Behold, the day! Behold, it is coming (7:10‑13).

This woe oracle is against the materialism of the day. Their evil has grown like trees (the rod has budded, arrogance has blossomed, violence has grown into a rod of wickedness). The buyers and sellers will not make a profit. God’s judgment is sure (the vision), and no one will be able by means of his materialistic gain to save his life.

f. Blow the trumpet; get everything ready (7:14‑22).

I have read the imperative (tiqe’u bataqo'a and vhaken וְהָכֵן ). The shout to Israel is to prepare for war. Yet, with all their preparation, no one will go into battle, because that would be futile. Yahweh Himself will be fighting against His people. The evil triumvirate (sword, plague, and famine) will again be active. Even those who escape will be extremely vulnerable. Their material gains will mean nothing (7:19), and God’s beautiful things which they turned into idols will become abhorrent to them. God will deliver them over to foreigners and turn His face against them.

g. Make the chain! (7:23‑27).

This Hebrew is difficult, but as it stands, it is telling someone to prepare to take captives. The reason is that the land is full of bloody crimes (judgment of bloods) for which it must be judged. Evil nations will then be brought against Judah as God’s instrument, and the pride of Judah will cease. They will look for peace, but not find it. They will seek a vision from the prophet, the law from the priest, and counsel from the elders, but they will all be gone (note Ezekiel’s dependence upon Jeremiah for this triad, Jer. 18:18). The royal house as well as the people will mourn in this judgment. Then (notice the repetition) they will acknowledge that He is Yahweh.

4. Ezekiel’s prophetic ministry is transferred to Jerusalem on September 17, 592 B.C. (8:1—11:25).

a. The relation of the two visions.

Ezekiel, through a trance, is transferred to Jerusalem where he sees idolatry being practiced in the temple. The purpose of this vision is to give the reason for God’s judgment upon the city. The people have given up hope in Yahweh: they fail to recognize that their disobedience is the cause of His absence. They have turned to other gods for help. The references to the Living Creatures in this unit (9:3) is to tie together this vision and the one in chapter 1. The Living Creatures showed the glory of God in exile (Chs. 1‑7); now they show the glory of God leaving Jerusalem (Chs. 8‑11).

b. The setting of the vision (8:1‑4).

While Ezekiel was sitting among the elders of the exile, God appeared to him again. The spectral, semi‑human creature seems to be a theophany. The Spirit lifts him up and brings him in visions to Jerusalem. There he comes to the north gate of the inner court. (This could also be “the entrance of the inner gate facing northward” hapenimith haponeh tsaponah ). At that spot was located the “idol of jealousy that provokes to jealousy” (semel hqine'ah hmaqeneh pesel hassemel. It is instructive that a Canaanite goddess Asherah should be referred to by the Phoenician/Canaanite word semel.19

The glory of the Lord appears in the temple as it had appeared to Ezekiel in the plain (3:22). This device is used to tie the visions together (8:4).

c. The north side of the altar (8:5‑6).

Ezekiel sees the idol of jealousy (see above) and the people committing idolatry.

d. The entrance of the court (8:7‑13).

God tells Ezekiel to dig through the wall and there he sees theriomorphic images being worshipped. These would be similar to the art on the Ishtar gate. The seventy elders represent the leadership of Israel and show the pervasiveness of idolatry.

e. The entrance of the gate of the temple (8:14‑15).

God shows Ezekiel women weeping for Tammuz. This is an ancient Sumerian rite of weeping for the dying and rising God.20

f. The inner court of the temple (8:16‑18).

The people are worshipping the sun. Josiah got rid of horses and chariots dedicated to the sun (2 Kings 23:11). Manasseh built altars for the host of heaven (2 Kings 21:5). The “twig to the nose” may be a cultic gesture, but it is unknown.21

g. God brings judgment on the city and temple (9:1‑11).

The call for the executioners (lit. appointed ones: piqudoth, ) goes out and six men come from the upper (northern) gate. Each has his weapons of destructions, but one man, clothed in linen has a writing case (ink horn: qeseth hasopher, קֶסֶת הַסּפֵר). The man in linen is given the task of putting a mark on the foreheads of God’s faithful people. The other five are to follow after him slaying all those who do not have the mark, beginning with the elders before the temple. (Note the sealing of the 144,000 in Revelation 7.) As the five men began killing the people in the city, Ezekiel pled for the people. Yahweh’s response is that their sin is so bad, drastic measures are called for. His eye will not pity, but their conduct will be rewarded with judgment. The man in linen reports the completion of the task. This entire event probably takes place in a vision or trance.

h. God removes His glory to the east gate (10:1‑22).

God, who sits over the expanse above the living creatures, tells the man in linen to bring coals of fire from among the Cherubim (הַכְּרֻבִים). This is the first time the living beings are called Cherubim. They are otherwise known from Gen. 3:24, where they guard the garden, and they sit at either end of the ark of the covenant, where they seem to represent the throne of Yahweh, “who sits above the Cherubim” (1 Sam. 4:4). It is no doubt the Cherubim of the ark that are represented here carrying the glory cloud, a symbol of the presence of God (10:1‑5).

The coals of fire are to be scattered over the city (judgment is involved perhaps with the idea of purification). An extended description is given of the Cherubim showing that they are the same as in the vision of chapter 1. The only difference is that instead of an ox, the face of a Cherub is present. Does this indicate that a Cherub normally looked like an ox? (10:6‑17).

The glory of Yahweh (kabod) then departs from the threshold of the temple, stops over the Cherubim, who move to the east gate of the Lord’s house (10:18‑22).

i. God removes His glory from Jerusalem (11:1‑25).

At the entrance of the east gate, Ezekiel sees a certain Jaazaniah and a Pelatiah. These, says God, are those who plan iniquity in the city. Their plans seem to include the building of houses, i.e., there is no fear of further judgment. From later verses, it appears that they have taken over land forsaken by those who have gone into captivity. They are “land speculators.” They use a proverb that is cryptic to us: “The city is the pot and we are the flesh.” This seems to be used in a good sense: “we are the stuff out of which good soup is made, and the city is what produces it” (11:1‑4).

God uses the proverb against them. The dead in the city (from 597) were the flesh and the city the pot, i.e., the proverb is used negatively. The city will not be a place of protection; God will bring them out and slay them in the borders of Israel. Then they will acknowledge that He is Yahweh (11:5‑12).

Ezekiel again protests that Yahweh is going to destroy Israel completely when he sees Pelatiah die. Yahweh’s answer is found in the rest of the chapter. These “land speculators” are saying: “They have gone far (read the indicative rather than the imperative) from the Lord (temple in Jerusalem); this land has been given us as a possession.” They are growing rich on the misfortune of their fellow Jews. God says: “On the contrary, no matter how far I have removed them, I will bring them back and give them the land of Israel.” There will be genuine conversion (Jer. 31:31), idolatry will be over, they will be “My people, and I shall be their God” (11:13‑21).

Finally, the Cherubim fly away with the glory of the Lord riding on them and stop over the Mount of Olives. Then the Spirit brought Ezekiel back to the exiles in Chaldea. He then reported this extraordinary vision to the exiles (11:22‑25).

5. Ezekiel, back with the exiles, predicts the deportation of the remaining Jews in Jerusalem (12:1‑28).

a. Ezekiel acts out an escape attempt (12:1‑7).

It would appear the people of the golah refuse to admit that God is going to punish Jerusalem. God therefore tells Ezekiel to act out the removal of the people from Jerusalem. The first step is to pack a bag and to move from his home to another place in the daytime. Then at night, he is to dig a hole through the wall, cover his face, and try to escape. Ezekiel did all this (12:1‑7).

b. God tells Ezekiel to declare the meaning of his act (12:8‑16).

The daytime movement represents the capture of the people in general. The night escapade represents Zedekiah’s attempt to escape the Babylonian army. God throws His net over him, and he is captured by the Babylonians. The rest will be scattered, but He will leave a few to spread the news of God’s judgment. Then they will acknowledge that He is Yahweh.

c. God tells Ezekiel to act out a life of fear (12:17‑20).

Ezekiel is to eat his bread and drink his water with trembling, quivering and anxiety. This is to symbolize the fear of the Jews in the foreign countries into which they will be taken captive.

d. God rebukes the Jews for discounting the prophetic messages (12:21‑28).

The Jews are quoting a proverb: “The things that have been prophesied must be for a distant future, because nothing is happening as prophesied.” (They say this in spite of Jeremiah’s prophecies.) Yahweh’s answer is that the days are drawing near and the vision will indeed be fulfilled. The false prophecies will fail. To those who declared of Ezekiel’s visions, “they must be for a distant future,” God says “None of My words will be delayed any longer.”

6. God tells Ezekiel to speak out against false prophecy (13:1‑23).

a. The practice of false prophets (13:1‑7).

False prophets were apparently fairly common in Israel’s history from the beginning of the Monarchy on down. Jeremiah encounters them personally and confronts them (Jer. 28,29). God tells Ezekiel to speak out against them. They prophesy from their own inspiration (lit.: “their heart” milibam, מִלִּבָּם). They are foolish prophets (hanevalim, הַנְּבָלִים), who are following their own spirit. The proverb “like foxes among ruins” points to selfish prophets: they do not build or maintain the wall, but they run around on it like foxes making dens. Their vision is false, and Yahweh has not spoken through them.

b. The judgment on the false prophets (13:8‑16).

God promises that false prophets will not be allowed in the council of Israel nor written in the register of the temple (census list). Their message is one of peace when there is nothing but disaster ahead. We know from Jeremiah 28 that the false prophets were teaching an early return from the exile. They are “whitewashing” the situation. The wall is dangerously weak, but instead of recognizing that fact, they paint it over with whitewash (false comfort). God promises to fulfill his judgment (symbolized by the falling wall against which He will send a storm).

c. Ezekiel is to prophesy against the false female prophets (13:17‑23).

This paragraph indicates that the men were not alone in their false prophecy. Certain women likewise were misleading the people. These “fortune tellers” instead of submitting to divine providence, try to tell people who will live and die.22 The bands on the wrists (kesathoth, ) and the head coverings were probably some magical garments with which they enticed and ensnared people. The handfuls of barley and pieces of bread may refer to incantations or to offerings. God promises to judge the women for deceiving the people into ignoring Ezekiel’s warnings.

7. God condemns internal and external idolatry (14:1‑23).

a. God criticizes the elders in the exile (14:1‑5).

The elders take their place before Ezekiel, presumably to receive a word from the Lord through him. God tells Ezekiel that the elders have set up idols in their hearts. This surely means that they are still worshipping idols even though it may only be internal. The second thing they are doing is putting “the stumbling block” of their iniquity (mikshol ‘evonam מִכְשׁוֹלעֲוֹנָם) before them. This is another form of mental idolatry “a rubric for an unregenerate state of mind.”23

b. God promises punishment on men who do this thing (14:6‑11).

Yahweh demands repentance and complains of the audacity of these who would carry on this idolatrous practice and then come to Yahweh for an answer to their inquiry. God says that he will deal directly with such a person. “I Yahweh will by myself oblige him with an answer.”24 God will set his face against that man. Furthermore, any prophet who deigns to answer such an inquiry will be held accountable to God.

c. God speaks of the irrevocability of His judgment (14:12‑23).

God speaks of his four‑fold messengers of judgment: famine, wild beasts, sword and plague. Once He has decreed these against a disobedient people, no one will be able to turn Him back. Not even the intercession of Noah, Daniel and Job would change the situation. Daniel is a contemporary of Ezekiel and as such is thought by some to be too young to have such a reputation. Many seek to find this Daniel in a more ancient personage such as the Danel of the Ugaritic epics.25 This latter has not enjoyed much popular support recently, but few critics believe this could refer to the Daniel known in the Bible. However, Daniel’s wisdom must have become quite well known since he interpreted Nebuchadnezzar’s dream even before the exile that brought Ezekiel to Babylon (14:12‑20).

God applies the principle to Jerusalem. He will indeed carry out His judgment, but at the same time he promises the deliverance of a remnant. This will bring comfort to Ezekiel because he will know that God has a purpose in what He is doing, and it will not be in vain (14:21‑23).

8. God likens Judah to a worthless vine (15:1‑8).

Vines have their value, but that value is not for woodworking. The vine‑wood is virtually worthless. When it has been burned in a fire, it is even less valuable. God then compares the vine to the people of Israel. Like the vine, they are worthless apart from God. The judgment to come upon them, like the fire to the vine, will not improve them any. Apart from God, Israel is worthless both before and after the judgment to be brought upon them. Their land is to be made a desolation because of their unfaithful response to Yahweh.

9. God rehearses Israel’s inglorious past but her promising future (16:1‑63).

a. Israel’s family tree (16:1‑5).

God ties Israel’s abominable practices into her heritage. Her family tree goes back to the Canaanites: her father was an Amorite and her mother was a Hittite. Amorite is a generic term similar to Canaanite (see Gen 15:16). The Hittites were a proto‑Hamitic people who were assimilated into their Indo‑European conquerors. The Canaanites epitomized all that God is opposed to. He was constantly trying to keep Israel from entanglements with them. (Note Abraham’s determination to keep Isaac from marrying a Canaanite—Gen. 24—and Isaac and Rebecca’s unhappiness with their son Esau for marrying one—Gen. 27‑28). When God found Israel, she was squirming as a naked little baby with no post‑natal care whatsoever.

b. God’s wonderful grace to Israel (16:6‑14).

God’s grace toward Israel is depicted in His care for this poor abandoned baby. He willed her to live (Patriarchs?), nourished her into adolescence (Egypt), married her and made a covenant with her (Exodus), cared for her, clothed her with ornaments (in the land under kings), so that all the nations heard of her. All of this was because God, in His grace, bestowed His splendor on her (16:6‑14).

c. Israel forgot God’s gracious acts (16:15‑22).

d. God speaks in this paragraph of the fact that Israel, as so often happens to people who have received mercy, forgot God’s grace and began to take pride in herself. This led to idolatry as she turned all God’s gracious gifts into idolatrous practices. The consummating evil was the sacrifice of children in the fire (to the god Moloch). Her worst “abomination” was to forget her awful past and God’s grace in rescuing her.

e. Israel’s “adultery” against her husband was heightened by turning from Him to the various nations (16:23‑34).

In the fourth year of Zedekiah (593 B.C.) we know that there was trouble in the Chaldean empire that led Judah and her neighbors to conspire against Nebuchadnezzar (Jer. 27‑28). This paragraph is to say that Israel, every time she went to other nations for help, was committing adultery against her husband, Yahweh. She should have trusted Him. He specifically mentions Assyria, Egypt and Chaldea. Ahaz was the first to go to Assyria under the threat of the Syro‑Ephraimite coalition (Isa. 7). Hezekiah, Ahaz’ son, received ambassadors from the newly emerging Chaldean power group (Isa. 38‑39), and under Zedekiah, efforts were made to persuade the Egyptians to take on the Babylonians (Jer. 37 cf. also Isaiah 23 which may indicate that Hezekiah was doing the same). By going to the nations for help rather than trusting Yahweh, she was committing adultery against her husband. Judah, however, was an adulteress, not a harlot. A harlot collects pay for her services, but Judah pays her lovers (an allusion to taking the temple gold, etc., to buy off foreign powers).26

f. God’s judgment will be to turn her “lovers” against her (16:35‑43).

God is going to call together these nations whom Judah has “lusted” after and bring them against her. They will not spare her. She will be stripped naked and treated like an adulteress. Her houses will be burned and the people will be put to the sword. Like an offended husband, Yahweh will find his anger appeased when all this happens. God’s purpose in punishing Judah is to bring her to the point where she will stop committing lewdness.

g. God concludes this discussion of Judah’s sordid past by discussing her relation to her sisters (16:44‑59).

God quotes another proverb to make His point: “like mother, like daughter.” The mother is a Hittite and the father is an Amorite. Judah’s conduct is what one would expect from someone who has such a family background. Her sisters also were adulteresses.27 Her older sister was Samaria and her younger sister was Sodom. These of course represent two groups who have already received God’s judgment because of their sin. Judah, however, has not learned from her sisters so that she acts even more wickedly than they. Her conduct is so disgraceful that she makes Samaria and Sodom look good by comparison. God however is going to restore Sodom as well as Samaria and Judah. All three of these groups will return to “their former state” that is prior to their wicked acts (cf. Matt. 11:20‑24.)28 Judah was so proud she would never even mention the name of her sister Sodom, that is, she disdained her. Now that her sin has been uncovered, Edom will mock her. God will judge her in proportion to her sin: she has broken His covenant.

h. God gives a comforting message of restoration (16:60‑63).

This paragraph contains a marvelous promise of complete forgiveness and restoration for Judah. Along with Samaria and Sodom, God will make a covenant with Judah and she “shall know that He is the Lord.” She will then always remember her shameful fall and will bask in the forgiveness of God. “Not because of your covenant” indicates that He will deal independently with the others.29

10. God gives the parable of the two eagles (17:1‑24).

a. The first eagle (Babylon) (17:1‑6).

The eagle is quite outstanding. He comes to Lebanon and takes away the top of the cedar tree (top is tsamereth, usually wool, perhaps the wooly appearance of the top of the cedar trees). The cedar trees in the Bible are used to depict pride, because the cedar wood was a very special wood coveted throughout the Middle East. Since the cedars grow in Lebanon, that place name will often accompany the symbol even though the referent is to some other place. Its top or best twig was brought to a land of merchants kena’an, ) and set in a city of traders rokalim, רכְלִים) (cf. Revelation 17‑18). He also took some of the seed of the land and planted it in a fecund place. The branch and the seed turned into a vine which inclined toward the eagle (Babylon as its protector). However it kept roots under it (Jews in Jerusalem).

b. The second eagle (Egypt) (17:7‑10).

The vine begins to reach out toward the second eagle for sustenance. The action seems to be effective because the vine is fruitful. However, God says that He will pull it up and let it wither.

c. The interpretation (17:11‑21).

God’s teaching about His place in the events of the last days of the monarchy is very instructive. The royal covenant made with Zedekiah and the oath that goes with it are from God (17:19). The deportation to Babylon is considered to be good (cf. the good figs in Jeremiah 24). In all these tragic events of the last quarter century of the monarchy, God declares Himself to be completely in charge. It is wrong to rebel against Babylon and to go to Egypt or any other nation for help.

The first eagle represents Babylon. The top twig represents Jehoiachin taken to the city of merchants (Babylon). The seed represents Jews deported in 597 B.C. The second eagle represents Egypt to whom Zedekiah and his advisors were looking for help against Babylon. Egypt promised to help and actually fielded an army so that the Babylonians pulled back temporarily. But they did not provide a permanent support.

d. God declares that He will one day set up a special twig that will rule (17:22‑24).

Ezekiel delivers another message of hope. The twigs mentioned so far are being rejected (cf. a similar message in Jeremiah 23 where the kings of Judah are rejected but the Messiah [the branch] is promised). This twig will be put on a high mountain where it will become a stately cedar and a place of refuge for birds (cf. Nebuchadnezzar’s kingdom in Daniel 4). Furthermore, the other trees (kingdoms) will learn of the sovereignty of God. “He puts up one and sets down another.”

11. God gives a message on human responsibility (18:1‑32).

a. God teaches His sovereignty in human affairs and that He does not discriminate (18:1‑4).

The Jews were complaining that their suffering was the result of their ancestors’ sin. They quote the parable about sour grapes. God argues that everyone belongs to Him and the He will see to it that individual responsibility is enforced (cf. Deut. 24:16).

b. God says that the righteous man will live (18:5‑9).

It is important to remember the context. Life and death in this chapter refer to physical not spiritual states. It is not clear whether God is saying that He will see that a wicked man dies or whether the community should follow up on the sin, but it is clear that he is teaching individual responsibility. The righteous man who:

is righteous and practices the same

does not become involved in idolatry

does not commit adultery

does not violate menstrual laws

does not oppress, but restores pledges

does not rob, but gives bread and clothes to the poor.

does not lend money on interest

keeps his hand from iniquity

sees to justice between people

walks in God’s statutes and ordinances

will live!

c. God says that the unrighteous man will die (18:10‑13).30

The righteous man may have a son whose conduct is opposite that of his father. That man will not live, says Yahweh. His blood will be on his own head when he is put to death.

d. God says that the righteous grandson will not be punished for his father’s sins (18:14‑20).

Apparently, their popular theology did not teach that a father’s good deeds would compensate for a wicked son’s bad deeds, but it did hold that a father’s wicked deeds would be passed on to his son. God emphatically denies that dictum. The grandson, who lives a godly life as his grandfather did, will live regardless of what his father was like.

The people insist that the son should bear the sins of the father.31 That passage is probably talking more about the natural consequences of a father’s sins being passed onto succeeding generations). However, God insists that each will be judged by his deeds (See Exodus 20 for further discussion).

e. God says that changed conduct will change divine attitude toward the person (18:21‑32).

God’s grace responds to repentance. The wicked man who turns away from his sin, will encounter God’s forgiveness, and his sinful past will not be held against him (18:21‑23).

Conversely, the righteous man who abandons his good conduct will encounter God’s judgment, and his past goodness will not avail him God’s favor (18:24).

Regardless of human opinion, God says that his ways are the right ways, and the people are wrong in their philosophy. God does not take pleasure in the death of the wicked, but he is just and will deal justly (18:25‑29).

This true philosophy applies to Israel. God calls upon her to repent, to turn back to Him. They are to make themselves a new heart and spirit lest they die. God takes no pleasure in anyone’s death—therefore, He exhorts them to repent (18:30‑32).

12. Yahweh gives Ezekiel a lament against the royal leadership of Judah (19:1‑14).

The form of this prophecy is a lament (qinah, קִינָה). It is directed to the princes of Israel. Their mother is described as a lioness with cubs. The first cub was reared to be a leader but was deported to Egypt (this would have to be Jehoahaz since he is the only one to go to Egypt). The second “cub” was taken to Babylon (this one must be Jehoiachin, since he is the first one who went to Babylon. Jehoiakim is being passed over). Finally the “mother” (Judah) is referred to as a vine which in spite of its once fruitful condition, has been plucked up and thrown into the desert where it cannot produce. In other words, there will be no more leaders in Judah to deliver her.

13. On August 13, 591 B.C. Yahweh speaks to the elders who come to inquire of Him (20:1‑44).32

a. Yahweh takes the opportunity of the elders’ visit to challenge them with the lessons of the past. He refuses to respond to their request, but rather calls upon Ezekiel to judge them for their conduct. The elders are representing the nation of Israel, therefore, this message transcends the golah of Babylon and applies to all the people of Israel. He recounts Israel’s history and shows their sinfulness and His grace up to the present time (20:1‑4).

b. The first stage is the sojourn in Egypt. There they disobeyed him (apparently when Moses approached them about bringing them from Egypt) and refused to put away their idolatry. God considered pouring out His wrath upon them, but chose not to “for His name’s sake” lest it be profaned among the nations (20:5‑9).

c. The second stage is in the wilderness. God gave them His covenant (Exodus 20) and His Sabbaths as a sign. However they rebelled against Him (Exodus 33), and He again considered annihilating them. Again, He restrained Himself because of His name (note in Exodus 32 that Moses interceded for Israel with the same argument about the inviolability of God’s name). However, as punishment, He told them they would not go to the land, but die in the wilderness (20:10‑17).

d. The third stage is the offspring of the wilderness rebels. These children who were allowed to live even though their parents died in the wilderness did not learn the lesson God gave them. They also became involved in idolatry. God again considered annihilating them, but held back His hand because of His reputation among the nations. He did give them the Deuteronomic covenant containing curses for disobedience (statues not good; ordinances not resulting in life, 20:25) (20:18‑26).

e. The fourth stage is in the land. Once in Canaan, they began to adopt the pagan practices around them. They learned of the “Bamah’s” or high places. They determined to be like the other nations around them. In light of this, should Israel seek to inquire of Yahweh (as the elders are doing)? (20:27‑31).

f. The final, eschatological stage is when Yahweh restores His people. This paragraph is an extraordinary statement of God’s future grace in behalf of His people. While the Jews may think they can act like all the other nations, Yahweh will not allow them to. He will be king over them. Two things must happen: He will regather the people and purge them of sinners. They must “pass under the rod” and be brought into the bond of the covenant. In the present time, they may indeed serve their idols (20:39), but in the future time they will be gathered on the mountain of Israel where they will serve Yahweh and He will accept them. They will hate their past life and “know that He is Yahweh, and that He has dealt with them in accordance with His reputation” (20:32‑44).

14. Yahweh speaks through Ezekiel a prophecy of the imminent fall of Jerusalem (20:45—21:32).

a. The last five verses of chapter 20 are included in chapter 21 in the Hebrew where they belong. The first unit (20:44‑49) is a “parable” against Jerusalem, the second unit is an explicit statement (responding to the cynical statement “he is just speaking parables”).

b. There is no forest in the Negeb. Therefore, “the southland” (Teman), “the south” (Negeb), “against the south” (darom, דָּרוֹם) are all terms for Judah.33 God predicts an unquenchable fire in Judah. Perhaps the south is viewed as the starting point of the conflagration. From there it will spread northward as does the sword in the following paragraph. Everyone will know that it is Yahweh who has done it (20:44‑49).

c. Yahweh states explicitly that this prediction is against Jerusalem. Both righteous and wicked will suffer when Yahweh’s sword goes forth (again “all flesh will know that the drawn sword is from Yahweh”). The sword will cut from south to north. Ezekiel is told to groan with breaking heart and bitter grief. The people of the golah will ask him what he is groaning about, and he will reply that it is because of the news coming imminently about the disaster. This refers to the soon to be announced fall of Jerusalem (21:1‑7).

d. This message is against the people of God and the officials of Israel (21:12). Therefore, Ezekiel is to show signs of grief (strike your thigh). But it will get worse as the sword multiplies its efficiency against the people. But God will appease His wrath by bringing judgment on His disobedient people (21:8‑17).

The phrases “Or shall we rejoice, the rod of My son despising every tree?” (21:16) is virtually impossible to translate. It makes some sense if we assume it means that “My son” refers to Nebuchadnezzar attacking the people of Judah (trees). 21:18 has a phrase with several of the same words: “for there is testing [Babylonian invasion?]; and what if even the rod [Zedekiah?] which despises will be no more.” The difficulty in the text leaves the translation tenuous.

The Hebrew of the two phrases is:

אוֹ נָשִׂישׂ שֵׁבֶט בְּנִי מאֶסֶת כּל־עֵץ 21:16

כִּי בחַן וּמה אִםגַּםשֵׁבֶט מאֶסֶת לאֹ יִהְיֶה נְאֻם אֲדנָי יהוה 21:18

e. The sword imagery continues through the symbolic word: Ezekiel is to mark out two roads with a sign post. One sign will read “Rabbah of Ammon”; the other will read “Jerusalem.” Nebuchadnezzar will stand at the crossroads trying to decide which way to go. He will practice divination (arrows, idols, liver) and the answer comes: “Jerusalem.” However, the elders in the golah cannot believe it. They declare it to be a false divination (Nebuchadnezzar has made a mistake? or Ezekiel has made a mistake in interpretation?). Yet, God is reminding them of their sin and delivering them into the hand of Nebuchadnezzar. Furthermore, Zedekiah is looked upon as a slain, wicked one. His royal dignity will be removed. Jerusalem will be a ruin, and yet there is hope: One is coming whose right it is to rule and God will give it to him34 (21:18-27).

The Ammonites (the other road sign) will not escape even though the divination of Nebuchadnezzar led him to Jerusalem. He will come back against the Ammonites and judge them severely (21:28‑32).

15. Yahweh calls on Ezekiel to judge Jerusalem for her sinfulness (22:1‑31).

a. Jerusalem first is attacked for her idolatry and the shedding of blood. They have become a reproach to the nations as God’s judgment on her (22:1‑5).

b. The rulers are next singled out because as God’s representatives, they are expected to live exemplary lives. Instead they:

treated father and mother lightly.

oppressed the alien.

wronged the widow and the orphan.

despised God’s holy things.

profaned God’s Sabbaths.

shed blood.

ate at mountain shrines.

committed acts of lewdness.

uncovered their father’s nakedness.

violated the menstrual laws.

defiled daughters‑in‑law.

humbled step‑sisters.

took bribes for murder.

took interest.

injured neighbors for gain.

forgot God.

Their sin will be punished by dispersion among the nations (22:6‑16).

c. Judah is compared to dross. God must smelt the metal and remove the dross. Jerusalem will be the pot and he will set a fire under her, and then they will know that Yahweh is the one who has poured our His wrath (22:17‑22).

d. Judah is compared to a polluted land that needs cleansing by rain. The prophets conspire for their own ends (23‑25); the priests profane holy things (26); the princes are like wolves (27); the prophets whitewash everything, and the people practice all kinds of sin (28‑29). God searched for a man to stand in the broken down wall to stave off His judgment, but He could find no one. God therefore must judge them (22:23‑31).

16. Yahweh gives Ezekiel a tale of two sisters (23:1‑49).

a. There were two women, named Oholah (tent = אָהֳלָה) and Oholibah (a tent in her = אָהֳלִיבָה, cf. Jer. 3:6‑10 for the same motif). These names are apparently linked to the Tent of Yahweh (= the tabernacle, ‘ohel mo’ed, אהֶל מוֹעֵד), i.e., these people were related to the Lord. They were sisters and while in Egypt committed harlotry. Harlotry and adultery have two significances, both of which are found in this chapter: religious apostasy and political dependence on other nations rather than on God (23:1‑4).35

b. Oholah (Samaria) committed harlotry with Assyria. In graphic terms God depicts the sin of Samaria in pursuing Assyria. Finally, God turned them over to the Assyrians who took them into captivity (23:5‑10).

c. Her sister Oholibah should have known better, but she also pursued lovers: (Ahaz) went after the Assyrians (Isa. 7:14); then (Hezekiah) went after the Chaldeans (Isaiah 38‑39); now (Zedekiah) is going after Egypt (23:11‑21).

d. It remains that the same fate that befell Samaria must also befall Jerusalem. God will bring all Jerusalem’s lovers against her: Babylonians, Chaldeans (viewed as a sub‑group), Pekod, Shoa, and Koa (these three are usually considered peoples in southern Mesopotamia allied with Babylonia), Assyrians (conquered and now in Babylonia’s army). These will come against Jerusalem and strip her bare. When God does this through her enemies, he will remove her harlotry which she has been practicing since Egypt. They will be made to drink the cup of Samaria (23:22‑35).

e. The second aspect of harlotry is stressed in this paragraph. Jerusalem (Oholibah) has become involved in the religious practices of all these nations. He lists all the profane things they have done: idolatry, child sacrifice, defiled His sanctuary, and profaned the Sabbaths. He then turns back to the political alliances (40‑44). However, she will be judged as a harlot and will be stoned to death by righteous men. Then they will know that He is Yahweh God (23:36‑49).

17. Yahweh gives a final prophecy of judgment against Jerusalem to Ezekiel on January 15, 588 B.C. (cf. 2 Kings 25:1) (24:1‑27).

a. The siege against Jerusalem began on the tenth day of the tenth month of the ninth year of the captivity. God gave Ezekiel prescience of this event so that he could speak to the people of the golah with authority (24:1‑3).

b. Through the parable of the stew‑pot,36 Ezekiel depicts the awful judgment about to fall on Jerusalem after a siege of just under two years. The judgment of God will result in cleansing of the filthy city. God has decreed it and it will come to pass (24:4‑14).

c. Yahweh illustrates the horrible suffering to come upon Judah through the drastic symbolism of Ezekiel losing his wife. When his beloved dies, he is not to show any signs of mourning. He dutifully went to the people of the golah and told them what would happen. That evening his wife died (24:15-19).

d. When they asked him about the significance of this awful event, he explained that he was a sign: what had happened to him would happen to the people of Judah (24:120-24).

e. Yahweh speaks to Ezekiel and tells him that He is going to remove Judah’s stronghold (the temple), their joy, the desire of their eyes, etc.: family members who will be lost in the captivity of the city. When the siege ends, a messenger will come to Babylon with the news, and Ezekiel will be released from his “dumbness,” i.e., being able to speak only when God directed him to do so (24:25‑27).

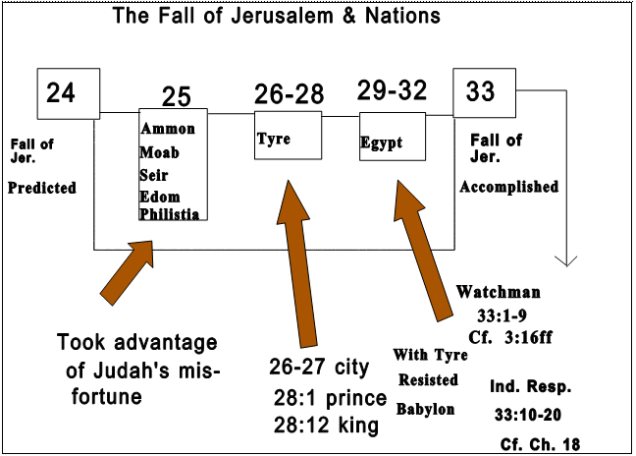

B. Prophecies against the nations (25:1—32:32).

The theology of the Book of Ezekiel is centered on the glory of God. He is willing to let His own name be blasphemed by the nations to bring justice on His covenant people. At the same time, the nations are under His control and cannot mistreat His people with impunity. These chapters are to show that the time of the nations has come.

1. Prophecies against the nations that have mocked Jerusalem (25:1‑28:26).

a. Ammon (25:1‑7).

In chapter 21, God told Ezekiel to draw crossroads and put up two road signs: To Jerusalem and To Ammon. Nebuchadnezzar then came to the crossroads and used divination to decide which way to go. The omens read “Jerusalem,” and he went in that direction. The fact that Nebuchadnezzar came to Jerusalem caused consternation to Jerusalem but rejoicing to Ammon. In chapter 25, God tells Ammon that they will not escape.

The sons of the east who will come against Ammon are the Babylonians, but they may include other people whom Nebuchadnezzar hires to fight for him (cf. 2 Kings 24:2).

b. Moab and Seir (25:8‑11).

The traditional enemies of Judah (Moab and Seir=Edom) were delighted to find that Jerusalem could fall to her enemies as any other people. They of course rejoiced in that fact. Therefore, God will treat their cities as Jerusalem has been treated. Again they will be given to the “sons of the east” for destruction. They will know that God is Yahweh.

c. Edom (25:12‑14).

Edom has not only mocked Jerusalem, they have in some way become actively involved in persecuting the distressed Jews. This is more explicitly dealt with in Obadiah who is probably dealing with this same event (see my notes on Obadiah and the comparison with Jeremiah). God will take vengeance on Edom through Israel. (Edom was subjugated by the Jews under the Maccabees.)

d. Philistines (25:15‑17).

The Philistines also suffered at the hands of Nebuchadnezzar, but they have, like the Edomites, taken an active hand in the suffering of the Jews. Therefore, God is going to destroy the Philistines (Cherethites is another, older name. See also Gen. 10:14).

e. Tyre (26:1—28:23).37

One must wonder why such an extensive amount of material is devoted to Tyre when she played a relatively insignificant role in the fall of Jerusalem. During David and Solomon’s time, Hiram king of Tyre was a friend of Israel. Jezebel, Ahab’s wife, was a Tyrian princess. Later, Tyre’s interests were strictly mercantile and not in an empire. It seems to me that Tyre has become such a symbol of arrogance and independence that God uses her to represent the rebellion and hostility exhibited by the nations against Him. Zimmerli says: “In 587, however, apart from Jerusalem, only Egypt and Tyre were in a state of rebellion against Nebuchadnezzar. In the case of both of these the rebellion continued for some years.38 It thus follows inevitably that the prophetic message must be concerned in a quite special way with Yahweh’s judgment on these two powers.”39

The time given in 26:1 is the eleventh year, but the month is not given. Consequently, the date can only be approximated at 587/6. However, this is during the siege and probably not too long before the capitulation because Tyre is rejoicing that the gateway has been broken. She (Tyre) believes this will be a great opportunity for her to prosper at Judah’s expense. However, God promises Tyre that she will be defeated and will become a place for the spreading of nets and spoil for the nations. The daughters on the mainland refer to the towns and villages on the shore as opposed to the island Tyre. This first unit is stated in general terms: many nations (plural) will come against her (26:1‑6).

The destruction becomes particularized as he describes one of the agents of destruction: Nebuchadnezzar, King of Babylon. He will slay people on the mainland and set a siege against the island fortress. Nebuchadnezzar will enter her gates and spoil her people. There will be desolation in Tyre as the harps are silenced and the Island fortress will return to its original status as a bare rock where fishermen will spread their nets (26:7‑14).40

How are we to reconcile the account of Ezekiel 26 attributing the disastrous fall to Nebuchadnezzar with Ezekiel 29:17‑20 and the extra-biblical accounts that indicate Babylon’s apparent inability to capture Tyre? Jerome says that the Tyrians carried off all wealth when it became apparent the city would fall.41 Thompson,42 argues for a general interpretation of Scripture (Tyre will fall) and not a specific fulfillment. Lawhead43argues for a negotiated surrender.44

Some would argue that the destruction of Tyre refers to a mainland city with that name, while the failure to gain pay (Ezekiel 29) refers to the island fortress. An Egyptian reference,45 from the thirteenth century B.C. indicates two cities: “Let me tell you of another strange city, named Byblos. What was it like? And its goddess? Once again—[thou] hast not trodden it. Pray instruct me about Beirut, about Sidon and Sarepta. Where is the stream of the Litani? What is Uzu [ed. note=“old Tyre on the mainland”] like? They say another town is in the sea, named Tyre-the-port. Water is taken (to) it by the boats, and it is richer in fish than the sands.”

More likely, however, the prophecy has both general and specific implications. Having begun in a generalized way: nations (1‑6), he became particular with Babylon (7‑11), but he became general again in v. 12. “They” (the nations) will despoil her. At this point we are looking to the subsequent devastating calamity under Alexander the Great (26:12-14).

The fall of Tyre, seemingly impregnable, will strike fear into the hearts of other Mediterranean powers. They will sing the lament song about this unexpected fall. Tyre personified will go down to Sheol, terrified. The earlier part of the chapter speaks in historical terms of the defeat of Tyre. Only in the last unit (15-18; 19-21) is a lament taken up using the stereotypical phrases found also in Isaiah 14 (26:15-21).

A long and beautiful description is given of Tyre’s greatness as a maritime power in chapter 27. Her ships, sail, awning, rowers, pilots, seam repairers and sailors are described as a vast force necessary for Tyre to carry on her trade. Tyre controlled the southern part of the Mediterranean all the way to the pillars of Hercules (27:1‑9).

Tyre’s army consisted of mercenaries from as far east as Persia and south to Lud and Put. This was an army to defend the island fortress as well as Phoenician trade in general (27:10‑11).

The world‑wide trade carried on by Tyre was astounding: Tarshish (Spain; known for silver mines), Javan (Greeks), Tubal and Meshech (Black Sea), Beth‑Togarmah (north) and Dedan (southeast), Islands, Aram, Judah and Israel (bought food stuffs), Damascus, Vedan and Javan, Arabia, Shebah, etc. Tyre was truly an international conglomerate! (27:12‑25).

This greatness, however, must come to an end. God will judge Tyre, and all her might will not prevent it. Nations will be amazed at her fall. (Note Revelation 17‑18 for a similar description of “Babylon”) (27:26‑36).

The first ten verses of chapter 28 are a judgment oracle on the Prince of Tyre. He is called the prince or ruler (nagid נָגִיד). Clearly here Ezekiel is speaking of a human being who has declared himself a god. S. Ribichini says “that the kings of Sidon, Byblos and Tyre were also high priests of Baalath, Astarte and Melqarth. In fact, for Phoenician kings at the time of the Persians, their religious role was more important than their royal title: in the Tabnith inscription the title ‘priest of Astarte’ comes before the attribute ‘King of the Sidonians’ in the description both of the king and of his father Eshmunazar.”46 The prince’s wisdom has brought him great wealth, and the ensuing pride has caused him to refer to himself as a god. Therefore, God will judge him and bring him down to death (28:1‑10).

Chapter 28:11-19 is one of the most difficult units in the Bible. It is cryptic, full of symbolism, and highly poetic. We must be careful not to divorce it from the context. The use of “King” instead of “Prince” may indicate two different referents or it may only be due to two different oracles from different periods. “Your trade” (28:16, 18) ties the unit to the others.47

Zimmerli cites some older critical scholars who see in the “King” some angel of Tyre, or gods of the nation.48 Some evangelicals argue that the unit refers to Satan. Feinberg struggles with the issue and tries to maintain both historical referent (Tyre) and supra historical referent (Satan).49 Keil does not even mention Satan in his discussion. “Created” means he became king; the garden of God refers to the ideal situation of Tyre, etc. The king is compared with Adam who was placed in ideal circumstances and yet rebelled against God. Alexander has moved toward this interpretation.50

There are problems if the unit refers to Satan:

1. He is called the king of Tyre.

2. The garden of Eden language sounds like Adam.

3. The garden of Eden is parallel to the Mountain of God (cf. 31:7-9).

4. V. 13 sounds like Adam.

5. Trade (16) sounds like Tyre.

6. Beauty (12,17) parallels the same idea in 27:4 where it is Tyre.

7. Wisdom (12,17) parallels 28:4,5 of the Prince of Tyre.

8. He is cast to the ground and put before kings (17). When?

9. What are Satan’s sanctuaries? (v. 18)

10. When/how was Satan turned to ashes? (v. 18).

11. You will be no more (19) sounds like Tyre in 26:21.

I am moving toward the opinion that we must begin with the historical referent of the king of Tyre (Ethbaal?). If this is the primary referent, then we must understand the language to be used metaphorically to refer to the position of excellence and glory held by the Tyrian king at God’s disposal. He, like Adam, would have been in an ideal situation from which he fell because of rebellion and was judged. On the other hand, the highly symbolic language is surely telling us more than what happened to the king of Tyre; it may at least allude to the force behind the throne as in Isaiah 14.

f. Sidon (28:20‑23).

Sidon the elder sister of Tyre, was eclipsed by the island city. She also is promised judgment from God that will lead her to the conclusion that Yahweh is God.

g. Conclusion (28:24‑26).

In this section we learn that the reason for the judgment on the nations was their attitude toward the Jews (28:26, cf. 25:3, 6, 8, 12, 15 and Matthew 25), and Tyre and Egypt possibly represent an arrogant rejection of Yahweh’s purpose for Nebuchadnezzar. God will remove that cause of suffering by His judgment on these various nations. Furthermore, God promises to regather Israel from all the nations and bring them back to the land. Then they will live securely and they shall know that He is Yahweh their God. This is the promised kingdom.

2. Prophecies against Egypt the ancient nemesis of Israel (29:1—32:32).

a. The time is January 6, 587.

Jerusalem is under siege and only eight months away from collapse. She still hopes desperately for some assistance from Egypt. There is no other place to look except to Yahweh, and they are unwilling to listen to Him. This first oracle is given to discourage going to Egypt for help. (There are at least six oracles here and perhaps more. The dates, from the 597 exile, are: 10/12/10 [29:1], January 6, 587; 1/1/27 [29:17], April 26, 571; 1/7/11 [30:20], April 29, 587; 3/1/11 [31:1], June 21, 587; 12/1/12 [32:1], March 3, 585; 12/15/12 [32:17], March 17, 585. This makes three in 587, two in 585, and one in 571.)

b. Under the imagery of a crocodile languishing in the Nile, Egypt is promised judgment by Yahweh.

To Israel they have been “a staff made of reed” which will only break and pierce the hand.51 The land of Egypt will become desolate, and then they shall know that Yahweh is God (29:1‑9).

c. Egypt will be judged (29:10-16).

God promises such devastating judgment on Egypt that they will be laid waste for forty years. This devastation will extend from the Delta (Migdol) to the first cataract (Syene, Asswan). This is like saying “from Dan to Beersheba.” The Egyptians will be scattered for forty years, but will be returned after that to form a lowly insignificant nation. As a result Israel will never again be tempted to put her trust in Egypt. (Note the history of Egypt from that time to this).52

d. The oracle coming from 571 (the latest in the book) is placed here to show the fulfillment of the first prediction against Pharaoh (29:17-21).

God will use Nebuchadnezzar, coming from Tyre with some frustration, to attack and defeat Egypt. God will “pay off” Nebuchadnezzar as his hired soldier with Egyptian spoil, since Tyre yielded so little. Thompson says: “The great campaign of Nebuchadrezzar’s later years was directed against Egypt in retaliation for the trouble caused by Hophra. Doubtless the Palestinian wars had resulted in many small expeditions,53 but it was Egypt which bore the brunt of his warfare. Hophra, the Egyptian king, who so basely left the cities of Palestine to their fate, brought nothing but evil to his own country, and after his disastrous expedition against the Greeks in Cyrene, a revolution broke out at home, where the people were utterly weary of his incapacity. He sent his general Amasis to deal with the revolutionaries, but they merely elected him as king, and in the end Hophra was practically dethroned, Amasis being elected co‑regent about 569 B.C. The small fragment of a Babylonian Chronicle first published by Pinches shows that Nebuchadrezzar launched an expedition against Egypt in his thirty‑seventh year, i.e. about 567 B.C. . . . the very distance to which he penetrated is a matter of dispute. One tradition says he made Egypt a Babylonian province, another that he invaded Libya, while Jeremiah ‘foretold’ that he would set up his throne in Tahpanhes, but there is no proof that he did so.” 54

e. God promises that a horn will sprout for the house of Israel (29:21).

This prediction may be messianic, but it could also refer to the power (Nebuchadnezzar) whom God will use against Egypt and in so doing, Ezekiel’s message will be authenticated.

f. The word of the Lord indicates that the Day of the Lord is coming to pass on Egypt (30:1‑26).

This phrase “Day of the Lord” often has eschatological implications, but in this context it refers to Nebuchadnezzar’s invasion of Egypt. Egypt will be totally defeated, regardless of her help, and her people will go into captivity. Egypt’s arms will be broken by the Yahweh‑strengthened arms of Babylon (cf. also Jeremiah 37:5).

g. Two months after the oracle of chapter 30, God compares Egypt to Assyria (31:1‑9).

The imagery is trees and forest. Assyria was a great tree; the birds of heaven nested in its boughs. No tree in God’s garden could compare with it.

h. However, the tree became very proud and God delivered it into the hands of a “despot” (‘el goyim, אֵיל גוֹיִם), who will deal with it appropriately (31:10‑18).

The tree will be felled and the birds will roost on its ruins. When the “tree” went down to Sheol, Yahweh caused a lamentation to be sung. Nations shook at the idea that it would go to Sheol. What makes you think, O Egypt, that you are any better? God’s judgment will come upon you in the same way.

i. Almost two years later (March 3, 585) Ezekiel is given another lament for Egypt (Jerusalem fell the preceding August) (32:1‑10).

This time Egypt is compared to a lion and a water monster. God promises to ensnare her with many people. Egypt will suffer horribly and nations will be astounded at her devastation.

j. A further oracle declares that the devastation is to be wrought by the King of Babylon (32:11‑16).

The cattle will be destroyed, and the Nile will be made low. Then they will know that Yahweh is God.

k. A final oracle is given on March 17, 585 (32:17‑32).

Egypt as an outstanding enemy of Israel will be brought to a final end in Sheol. However, she is not alone. The Gentile powers, so hostile to God’s purposes, and so arrogant against Him will also be there: Assyria, Elam, Meshech, Tubal, Edom, and Sidon. Pharaoh will be “comforted,” that is he will not be alone in his misery. He will see that he is not the only one who once had great power who has now been reduced to Sheol. This vignette is similar to that of the King of Babylon in Isaiah 14.

C. Messages of warning and encouragement in light of the fall of the city (33:1—39:49).

The nations oracle was placed between God’s promised judgment and the fall of Jerusalem to show that God will deal with the nations who punished Judah and rebelled against Yahweh’s agent, Nebuchadnezzar. He will bring about ultimate equity: judgment of the Gentiles and restoration of Judah. With that out of the way, God can then show the fall of the city to Babylon. The fall of Jerusalem is a turning point in the argument of the book. After admonishing those in Jerusalem who believe they can hold on without God and those in the golah who refuse to listen to Ezekiel, God denounces the false shepherds of Israel. Then as in Jeremiah 23, he promises a great shepherd to come. Chapter 35 is a prophecy against Seir (Edom) because of their activity in connection with the fall of Jerusalem.55 Ezekiel is now ready to turn his attention to the restoration of God’s people.

1. God prepares them for the message of the fall (33:1‑20).

The commission of Ezekiel (chs. 1‑3) included the fact that he was to be appointed a watchman to his people. This reiterated statement about the watchman is to impress upon the people the place and purpose of Ezekiel and to encourage the people to listen to what he has to say, particularly when they get the message of the collapse of Jerusalem.

a. The imagery of the watchman (33:1‑6).

The same basic description as in chapter 3 is repeated here. The watchman has an unbelievably important task of protecting his people. In such a situation, the consequence of negligence are of a capital nature. The blood of the people will be required of him—that is, he will die. On the other hand, when the watchman does all that is expected of him, the responsibility for refusing to make a proper response rests with the people. So Ezekiel speaks as God’s watchman. He has clearly warned the people; it is left only for them to repent or to harden their heart. The responsibility is theirs.

b. The issue of responsibility again (33:10‑20).

God dealt with the issue of individual responsibility in almost identical terms in chapter 18 in response to the “sour grapes” parable. It is being repeated for the same reason as the watchman parable. The news of the fall of the city is about to come; the people will say in despair: “Surely our transgressions and our sins are upon us, and we are rotting away in them: how then can we survive?” The answer is to repent. They cannot rely on any past righteousness they may have had, but even if they have been unrighteous, God will accept their repentance and forgive them. The Jews of that day felt that the righteous acts should balance out sin. They argue, therefore, that God is unfair. He responds that He is fair, but their way is not right. He will deal with each one according to his ways.

2. The message comes that Jerusalem has fallen (33:21‑33). (January 8, 585 B.C.) THE NEXUS OF THE BOOK

a. When the news comes about the fall of the city, Ezekiel is relieved of his “dumbness” and permitted to speak normally. This would mean that he was able to speak at will and not be limited to the times Yahweh spoke through him (33:21-22).

b. Yahweh speaks against those left in the land (33:23‑29).

In spite of the fall of the city, the people still have the audacity to believe that they will retake the land. After all, they say, Abraham was only one and he possessed the land. Why cannot we who are many do the same? They are incurable optimists. In answer Yahweh tells Ezekiel to tell them that no matter where they go, they will be pursued by the relentless hand of God and killed. The land will be desolated and they will know that He is Yahweh.

c. Yahweh speaks a word of encouragement to Ezekiel (33:30‑33).

The people of the golah were quite willing to listen to what Ezekiel had to say, but they were unwilling to pay any attention to him. He is like a beautiful song that people listen to and appreciate as music, but it has no lasting impact on their lives. However, when they see that all the things Ezekiel has prophesied have come to pass, they will know that a prophet has been in their midst. This latter promise was given to Ezekiel seven years before when Yahweh called him to the prophetic ministry (2:5).

3. Yahweh speaks to the shepherds and sheep (34:1‑31).

a. Yahweh speaks against the hireling Shepherds (34:1‑10).